Introduction

The convergence between culture and the political system, between attitudes, behaviors, and values, on the one hand, and institutional design, functioning and efficiency, on the other hand, has a vast literature having as a predominantly theoretical landmark the 1963 study by Almond and Verba.[1] Furthermore, the political culture in the manner defined and operationalized by the two authors „is one of the most powerful concepts in social sciences“[2], being an alternative to other political theory notions considering to have a lower scientifical relevance (mentality, ideology, civilization, etc.).

The political culture plays an important role in the community life, being responsible, through the set of values, attitudes, norms and ideals it entails, for its construction and evolution. It is also important in every individual’s life whose participation and integration in the social life is conditioned by the acquisitions of these values, norms and attitudes. „When we speak of the political culture of a society, we refer to the political system as internalized in the cognitions, feelings, and evaluations of its population“[3].

Every person relates to the political system at either the level of input, output or both. By input term or the political process, the two authors define the flow demands from the society to the political elite and the transformation of these demands into public policy. In this process the political parties, interest groups and mass media are primarily involved. The output term or the administrative process refers to the mechanisms by which these public policies are applied or imposed. It runs through bureaucracy and institutions involved in the juridical system (courts and tribunals).

The three attitudinal models proposed by Almond and Verba[4] facilitate and at the same time are based on distinct institutional constructions, being compatible with democracy to varying degrees. The prominence of the participatory dimension indicates a society in which the sense of the civic competence is characteristic for most individuals. Therefore, the characteristic of democracy is not a participant political culture but civic culture. For Almond and Verba, the civic culture is a mixed political culture in which the participant orientations are combined with and do not replace the subject and parochial political orientations. It is a political culture in which a large number of individuals are competent in their capacity as citizens[5].

A controversial concept

Although established at the level of Political Science and revitalized along with the structural changes in Central and Eastern Europe, at the end of the last century, the approach proposed by Almond and Verba has been repeatedly criticized and challenged[6]. It is one of the reasons Berezin scored a dividing line between the „old“ literature, which assumes the premise that the attitudes directly determine and condition the political practices, and the new trends in the study of political culture, which manifest by late 80s of the last century[7]. It is about a „rediscovery“ of the concept following a historical and ethnographic approach where culture (symbols and language) plays an instrumental role, facilitating political and cultural purposes, or actional approaches where the culture is a background for individual and collective political decisions, which influences the process of political transformation.[8] „The new literature on political culture is theoretical in that it challenges the concept itself; and it is historical in its careful attention to context and decided focused upon ethnographic and historical methods.“[9]

In fact, Berezin indicates three prevailing trends in the study of political culture, something that is mentioned also by Dalton[10]. He reviews the theory of „civic culture“ of Almond and Verba – „by far the most influential approach“, which establishes a causal relationship between behavior and values; the „authority-culture“ theory of Eckstein, which sets conditions between culture and political change; the theory of Wildavsky, which correlates specific social values and relationships, expressing distinct lifestyles.

Despite these distinctions and diversity of theoretical approach, the concept of „political culture“, at least in the manner it was defined by Almond and Verba, has its own limitations. For example, the typology formulated by the two researchers is more about quantitative aspects, such as the degree of information, involvement or non-involvement measure in the political and/ or administrative process, activism or alienation etc., all these highlighting the predominance of a certain type of political culture (participant, subject, parochial).

In addition, as noticed also by Kuhn, the concept of „political orientation“ (attitudes towards the political system and its various components, and attitudes towards the role of the self in the political system) is not clearly defined, often being mixed with terms like „attitudes“, „beliefs“ or other related formulas. Thus, „the question regarding which modes or types of orientations lie at the heart of culture is open to this day“[11].

Also, the analyzed value, attitudinal and behavioral universe has a national dimension, the possible differences, whether regional or between different socio-political categories, which may coexist within the same nation, being ignored. Social diversity, based on multiculturalism, i.e. based on distinct value orientations within the same national community can explain, equally, how the political system is structured and operates. The existence of a national political culture, even as a result of coagulation and centralization of regional political cultures is a doubtful reality. As a sum of the trends specific to the local communities, the identification of a national pattern can be forced, but its relevance is being easy questioned. Moreover, Putnam’s study on the development of regional government in Italy reveals the existence of sub-national socio-cultural peculiarities and also highlights their role in the performance of institutions. „Civic traditions help explain why the North has been able to respond to the challenges and opportunities of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries so much more effectively than the South“ says Putnam, for whom the „social context“, i.e., that specific functional environment of the individual, organizational and institutional interactions, is conditioned in value terms[12]. This is actually the departing premise for Almond and Verba, who define, operationalize and correlate the civic culture with democracy, but also for Putnam, who conditions the quality of governance (economic development and institutional efficiency) by the stock of social capital that an individual and a community hold. If for Almond and Verba the civic culture requires an as large as possible number of individuals competent in their capacity as citizens – able to exercise a political influence, for Putnam, a civic community is the community where the social capital records high levels. Civism, i.e. the involvement of citizens in all sorts of associative structures and their interest in community affairs is conditioned by the social capital. For Putnam, the civic community is based on solidarity, mutual trust and tolerance, i.e. those elements that define social capital.[13]

All these attitudes, feelings and knowledge that inspire and govern political behavior are not, however, uniformly distributed at the level of a national community, nor are they similar. The different ethnic and regional groups that coexist within the same borders often have different value systems and different ways to explain and understand the world, the social space, the authority. Furthermore, according to Diamond, differences in the fundamental axiological orientations are larger within the nations than between them.[14] Therefore „it is at least somewhat misleading to talk of the political culture of a nation, except as a distinctive mixture or balance of orientations“. His option is to disaggregate (national) political culture in „political subcultures“[15]. One more trenchant approach propose Reese and Rosenfeld, who believe that in order to express the cultural context of politics and policies, more suitable is the concept of „local civic culture“, defined as the sum of behavior patterns learned and acquired at the level of a local community (a city, for example). Investigating the relationship between civic culture and economic development policies,[16] the two researchers argue that for the classical literature in the field, the concept of „political culture“ is an appropriate one given its orientation, in particular, to a comparative analysis of national cultures.[17] Instead, the civic culture has a local dimension rather than a national dimension. „It refers more specifically to the life of a community, and thus, denotes the patterns or way of life in a local community“. „Civic culture“ is a concept equally wider and more focused than „political culture“. It is more concentrated as it applies in particular to local or municipal community and it is wider as it contains not only the way the people govern themselves but also wider cognitive and community behavior patterns.[18]

A short preview of Central and Eastern Europe

In Central and Eastern Europe, the research on political culture continued in the general „old themes of investigation“ and „it did not extend the theoretical borders“ to investigate attitudes and political behavior[19]. The traditions, specific values, cultural heritage are extensively used ingredients in the analysis of social and political changes in the former communist countries. The way the change itself was happened, its specificity, the duration and the model of transition, the functioning of institutions, they are all influenced, explained and analyzed in terms of the social context and specificities of the communist regime. „When a regime falls, and a new one is formed, the structure of the political power is disabled. Although the inheritance of the political past remains. The political culture theories underline that the past cannot disappear when a constitution is replaced by another; it persists in values and in politicians and citizens` beliefs socialized to accept the cultural norms of the previous regime.“[20]

On the basis of an extensive sociological research data,[21] Rose et al. emphasize the importance of attitudes, feelings and values of a community in the process of democratic construction. However, the cultural dimension of the change processes, with direct reference to the transitions in Central and Eastern Europe, do not receive much credit from the three authors. They relativize the relationship between political culture and democracy and question the direction in which it operates: is the culture a cause or a consequence of democratization?[22] Also, the three authors dispute the concept of national political culture which Almond and Verba operate with. Not unity but the variation characterizes the political values, beliefs, attitudes and behaviors of a national community.

These approaches are not singular. In the Romanian political space, there are voices in the academic and research field that sustain the existence of these regional particularities regarding the cognitive, affective and evaluative orientations of individuals to the political system. An example in this sense is that of sociologist Dâncu, who tries to explain the electoral behavior of the people from Ardeal invoking the existence in Transylvania of a political community different than the rest of the country, with a distinct identity, distinct values, needs and interest, a community which is closer in comparison to the Old Kingdom of Romania, of the civic community from the classical political culture theory. „Although it is a multiethnic community, in Transylvania the electoral campaigns do not reach the paroxysm from other regions. Less language violence, less hate. (…) A generically demand of the Transylvanian community is that of liberty, when the voters in other areas of the country concentrate on demanding goods, values, investments (…) As well as that, the community in Transylvania seems more conscious about common goals and the group interest. The political polarization is not as big as in Bucharest, (…). But the most important element of the explanation is the existence of a political identity problem. In Transylvania we have a deficiency of sense of belonging to the central politics, of political Romania, but not Romania.“[23]

There are also other researches that attempt to validate this thesis of Transylvania’s historical and/ or cultural differences with the other regions of the country. For example, Roper and Feșnic show that Transylvania is much more liberal and nationalistic in its orientation than the rest of the country, but also that the relationship between region and voter choice for pro-democratic parties is more ambiguous, in the context of important social cleavage within the region[24]. They support their allegation by analyzing the Transylvanian electoral options for different political actors in the 1992, 1996 and 2000 general elections. This is an interesting variable, but for a pattern of political culture, the general electoral activism is more important. Electoral participation, irrespective of the electoral option, is an indicator of political culture and, from this point of view, Transylvania is not necessarily a performer. In many of the sixteen counties of the region (including Crisana and Banat)[25], electoral participation is constantly below the national average. For example, according to official data from the Central Election Bureau of Romania, in the 2004 parliamentary elections only four counties (Covasna, Harghita, Hunedoara and Mures) had a higher ballot presence than the national average (59%), and in two other counties it reached this average (Salaj and Sibiu). In the 2008 elections, less than 50% of the Transylvanian counties registered an electoral participation above the national average (39%), and four years later only two counties (Harghita and Hunedoara) obtain this performance.

The literature also records more nuanced approaches, such as Bădescu and Sum[26]. They ask whether the development of civil society in Transylvania is different than in the rest of Romania (and if this difference can be attributed to differences in social capital) even if previous studies have identified no clear differences in democratic values or norms. The two authors compare the political values and behaviour in Transylvania relative to the rest of Romania and find out that differences persist, but not for all democratic values and norms. For example, support for democracy, trust in the rule of law or the standard measure of social trust do not vary across regions.

Mungiu-Pippidi also shows that, despite the coexistence of two cultures or national groups (Romanians and Hungarians) with very distinct identities, Transylvania is a single society, part of Romanian society. The hypothesis that this region has a „separate culture“ compared to the other Romanian regions[27] is sociologically invalidated. Practically, there is no culture of the Transylvanians, but rather a culture of „Romanians from Transylvania“ who identify themselves more with the Romanians from the rest of the country, and also a culture of Hungarians who tend to develop their own identity as „Hungarians from Transylvania“ (which is different from that of the Hungarians in a broad sense)[28].

Sandu made a more sophisticated analysis of the „social space of transition“. Based on survey data from the Sociology Department at the University of Bucharest (September 1995) and later on the data of the Public Opinion Barometer – Open Society Foundation (1999-2002), he identifies eighteen cultural areas by grouping, in the frame of a historical region,[29] the homogeneous counties in terms of development[30]. These social areas are considered „natural subdivisions of the historical regions.“ They are clusters of neighboring counties „with a level of maximum similarity from a social, economic and cultural perspective“[31]. Identifying the profile of trust, tolerance and sociability – the three basic components of the social capital – of the 18th cultural areas, Sandu highlights the heterogeneity of the historical regions, thus calling into question not only the existent of a national cultural pattern but also of the monolithic regional configurations. Therefore, the Romanian historical regions „have distinct cultural profiles related to the historical influences they have gone through, to the level of development, ethnic and religious composition. Neither economically nor culturally are these regions homogenous“[32].

Voicu reaches a similar conclusion too[33]. Although the volume coordinated by him, based on the European Values Survey and the World Values Survey data (Romanian waves), proposes an approach to national scale of certain value orientations related to democracy, institutions, religion or family,[34] the quantitative analysis reveals the existence of certain interregional differences[35] (or between different social status groups). Thus, with a higher degree of education and a higher standard of living, Bucharest „is distinguished in the level of modernity being significantly different from any other region of the country. The historical provinces, as a whole, do not have significant differences in the level of modernity, only Banat being considerably more modern than Dobrogea. However, the heterogeneity of these regions is an important one“[36].

Towards a national political culture

In relation to all these approaches, this paper aims to show that, in terms of attitudes, behaviors and political values, there aren`t many Romanias. The Romanian social space is quite homogeneous when it comes to the value orientations that structure the relationships between people, build models to understand and interpret the world and govern the manifestation of individuals in the public space as well as their reporting to the authority. In other words, in the case of Romania, one can talk about a national political culture. What I analyze is the link between belonging to a development region and political culture.

It is obvious that variance exists within the country. Ethnic communities, religious communities, rural-urban distinctions, etc., all these items of heterogeneity for a community generate variations in terms of values, attitudes and behaviors including political ones. But what this paper tries to bring to attention is that, in the case of Romania, these differences are insignificant to support the existence of different patterns of political culture across the country.

The proposed perspective is not necessarily contradicting the ones previously described, but rather complements them. Even though the authors mentioned above do not necessarily reject the idea of a national political culture, they tend to focus on variations to explain different outcomes within Romania. I do not deny the existence of these variations, but I argue that they are irrelevant to that set of values, attitudes and behaviors that define political culture. The statement is based on the results of a quantitative sociological research, which was done by surveying public opinion at the level of the eight developing regions, through a joint questionnaire.[37] Therefore, it regards a research conducted on representative samples at the regional level, which approaches a defining issue for the concept of „political culture“, such as trust in people, the social distance, the associativity, the dominant values, the civic and political participation, knowing and evaluating the political institutions and the civic competence. The main data and findings are exposed later on. They represent the arguments to support the statement according to which there are no major differences regarding the dominant model of political culture in the (developing) regions of Romania[38].

Political attitudes, behaviors and values – Sociological data

Social trust is a key element in the functioning of a democratic society and it refers both to trust in other people and trust in institutions. Trust in others requires the development of horizontal relations and corresponds to the „group dimension“ that Mungiu-Pippidi envisages in Romanian political culture analysis[39]. „Social trust facilitates political cooperation among the citizens, and without it democratic politics is impossible“. It helps to legitimize and strengthen the political system because „the sense of trust in the political elite – the belief that they are not alien and extractive forces, but part of the same political community – makes citizens willing to turn power over to them.“[40]

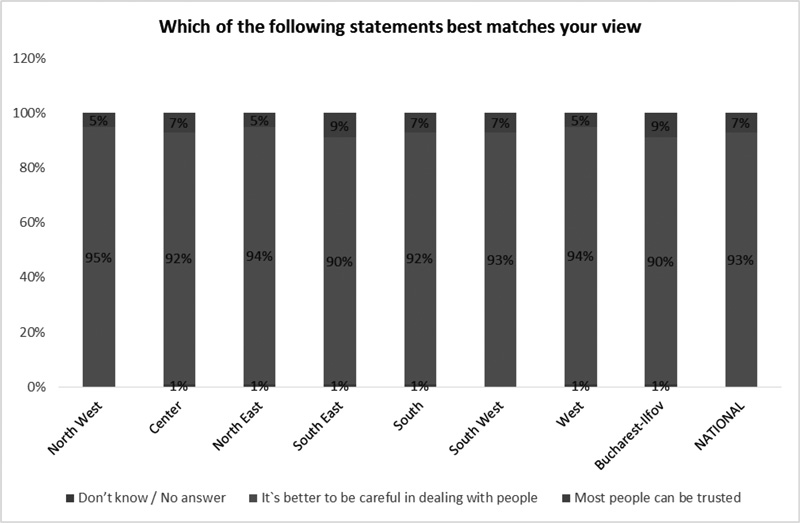

As it can be seen in Fig. 1, only 7% of the Romanians believe that they can trust most people. Social climate is one of distrust, with no significant differences between regions. The dominant feeling is the feeling of suspicion towards others, and this does not encourage cooperation between community members. This occurs primarily at those levels located closest to the individual: family, relatives, friends.

|

Fig. 1 – Trust in people |

|

| Click pe imagine pentru mărire |

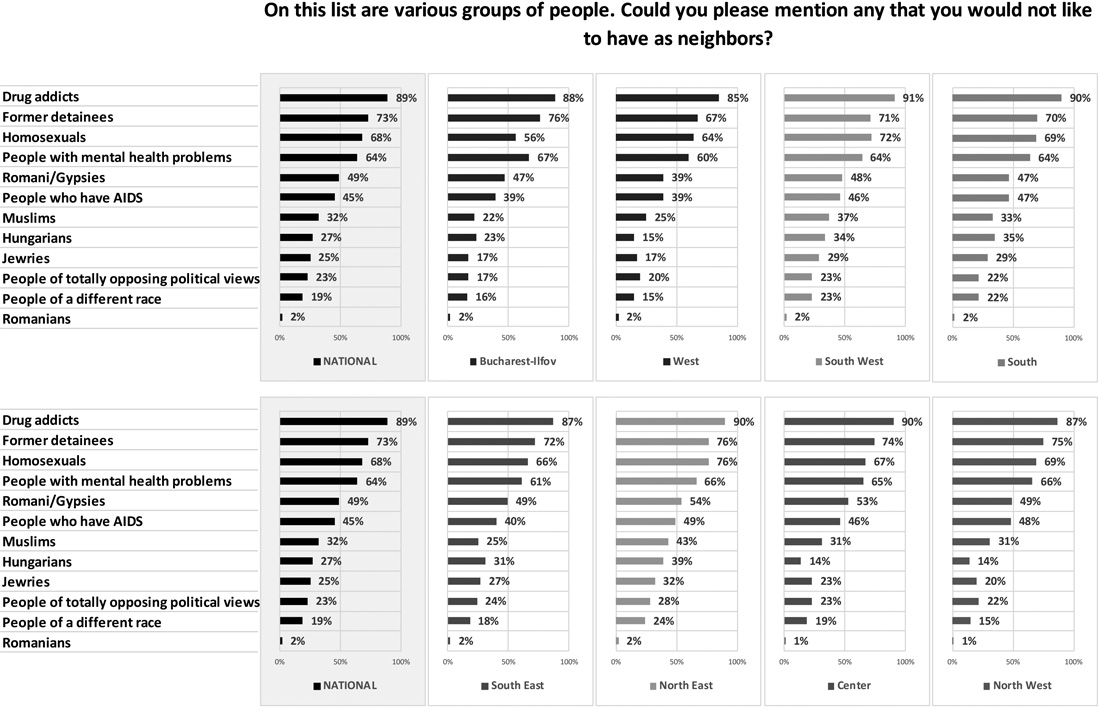

Generalized distrust is accompanied by a low level of tolerance towards individuals and groups considered „different“, which deviate from the social norm, ethnical, racial, religious etc. minorities. Basically, these categories of individuals are excluded from social interaction, such as is shown in Fig. 2. People addicted to drugs, those who were imprisoned, homosexuals or those with mental health problems record high levels of rejection, but intolerance is manifested also on Roma, Hungarians or Jews. And the differences between regions are insignificant and/ or punctual.

|

Fig. 2 – The social distance |

|

| Click pe imagine pentru mărire |

It is to be noted, however, the West Region, where the level of acceptance for all categories of persons covered by the question of social distance is below the national average, with significant percentages in the case of Hungarians (-12%), Roma (-10%), Jews (-8%) or Muslims (-7%). In the same category, of the areas with a higher level of tolerance, the region Bucharest-Ilfov is also included, which has scores well above the national average for homosexuals (-12%), Muslims (-10%) or Jews (-8%). At the opposite pole lies the North East Region, where there seem to be the most closed communities, with a low degree of desirability (above the national average) for many people, especially Hungarians (+12%), Muslims (+11%), homosexuals (+ 8%) and Jews (+7%).

Interesting to note is also the fact that in all the development regions of Romania, Hungarians record significant scores either below the national average or above it, with a peak of rejection in the North East Region and a maximum degree of acceptance in Center, North West and West. Also, the social distance in relation to Jews fluctuates with respect to the national average in most regions.

Despite these features, which could be explained largely by appealing to history, education or economic development, the differences between regions are not essential. In other words, belonging to a (development) region is not a factor that causes substantial different reports in relation to various categories of social groups. Romanian society is characterized by a low level of tolerance towards minorities.

|

Fig. 3 – Community cohesion |

|

| Click pe imagine pentru mărire |

With a direct correlation with the capital of social trust, collaboration with other community members in obtaining or producing a public good is an indicator of political culture. Trust and cohesion in society are necessary ingredients for the association, participation and civic engagement, and in the case of Romania, the percentage of 37% of those who have worked with other people in the locality to do something to benefit the community (see Fig. 3) argues in the favor of non-participating national profile. However, quasi-majority of Romanians perceive involvement in public affairs as a desirable behavior – 97% of the respondents agree that people should be more involved in the local community.

In terms of regional differences, they are, in this case, quite small. Homogeneity is relativized by the North East Region, with a percentage of community cohesion over the national average, and the South and Bucharest-Ilfov regions, with a lower level of collaboration between individuals, under the national average.

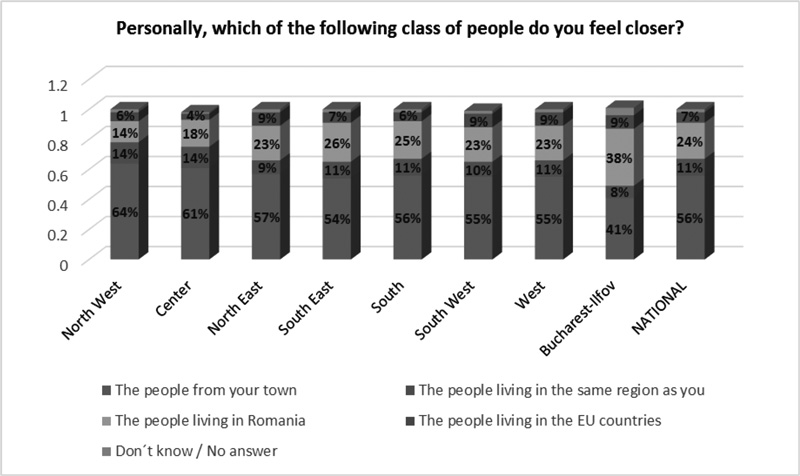

The existence of multiple identities can be a factor to justify the cultural differences within a national community. But the analyzed sociological data show quite clearly that a regional identity does not exist, at least not in the case of the developing regions.[41] Maximum values in this regard are recorded in the North West and Centre regions, but not exceeding 15% of the population, as shown in Fig. 4. The identity dominant for most Romanians (56%) is local. The exception is the Bucharest-Ilfov region and especially the capital, an important academic center and cosmopolitan urban agglomeration. The fact that Romanian identity is predominantly local does not necessarily speak to a national political culture, but it also points out that the regions are quite homogeneous.

|

Fig. 4 – Polarization |

|

| Click pe imagine pentru mărire |

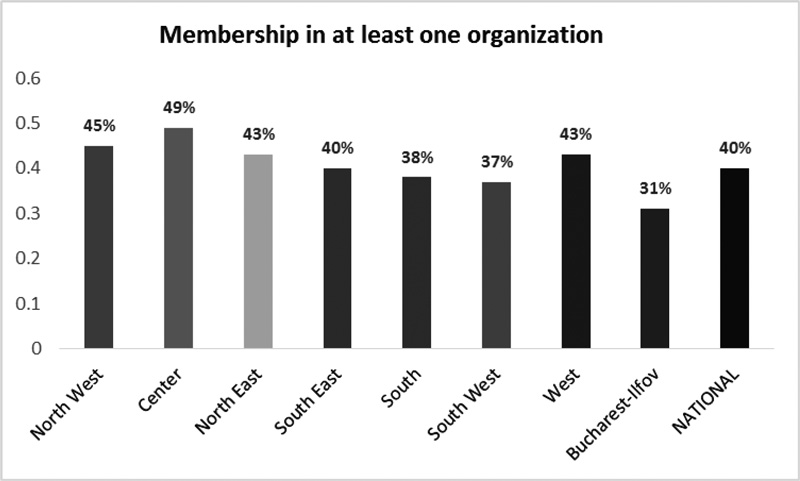

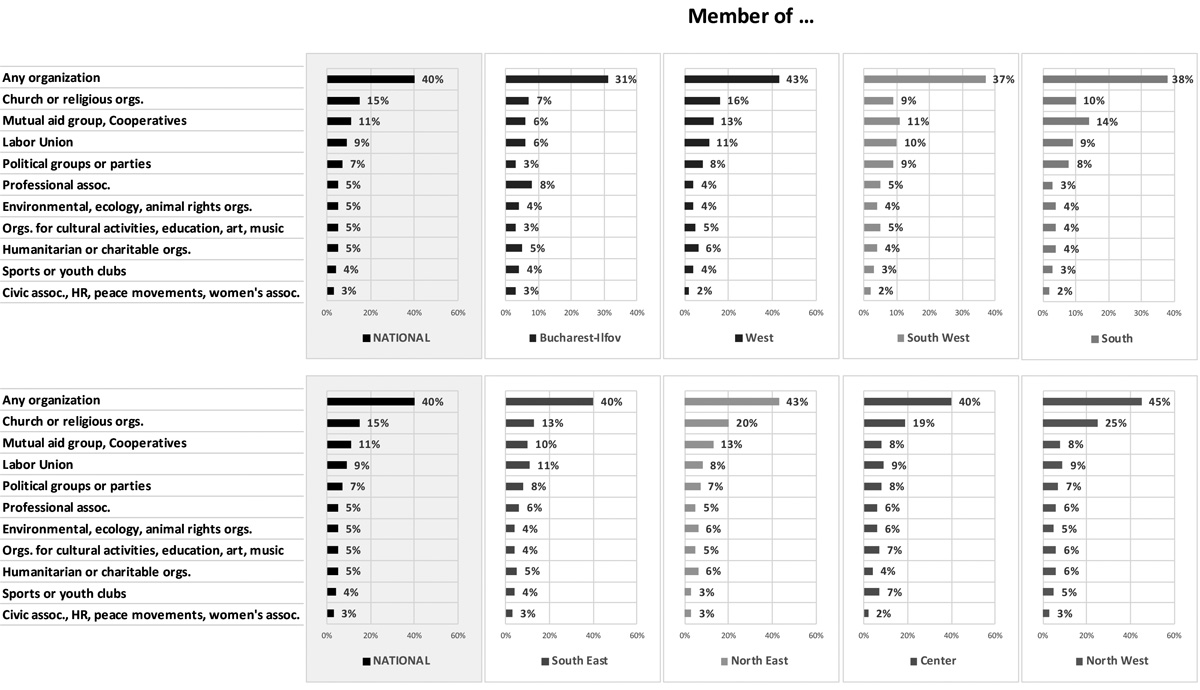

The association of individuals and the collective action to solve a problem existing in the community or to acquire a range of transferable skills are part of a pattern of behavior specific to consolidated democracies, where the citizens assume, in their capacity as rational actors, the civic activism. Basically, the cooperation within more or less formal groups is an active form of joining the interests and participation in social life. As it can be seen in Fig. 5, forty percent of Romanians state that they are members of at least one civil society organization. The distribution by regions is relatively constant, with no major differences. It can be noted however a higher degree of associativity (5% above the national average) in the North West Region, but also a percentage well below the national level in Bucharest-Ilfov region (-9%).

|

Fig. 5 – Associativity |

|

| Click pe imagine pentru mărire |

This reality acquires an explanation and becomes more evident and more comprehensive when we try to identify the types of organizations in which citizens are involved. Thus, as it can be seen in Fig. 6, participation as a member within structures of the civil society occurs especially at the level of the religious (traditional) associations or at the level of the social economy associations (credit unions and cooperatives). The fact that there is no systematic and assumed orientation of active involvement in open organizations, such as the civic, professional, cultural, environmental, etc. organizations could reflect a profile rather parochial of the community members.

|

Fig. 6 – Associativity |

|

| Click pe imagine pentru mărire |

Also in this regard, the regional differences are minor, and the punctual exceptions merely confirm the homogeneity of political culture. Basically, the percentage of those involved in religious organizations is higher in the North West (+10%), North East (+5%) and Centre (+4%) regions, but falls below the national average in Bucharest-Ilfov (-8%) and South West (-6%) region. Moreover, Bucharest records a lower level of membership in several types of organizations, such as credit unions and cooperatives (-5%) or political parties (-4%), but has a score something better as compared to the national average for the professional associations (+3).

Volunteering, i.e. that activity by which the individuals involve themselves in the community through collective action, offering pro bono their time, knowledge and energy in order to solve problems of common interest or to support other persons, is an important part of the civic culture. The sociological data analyzed in this paper show that about 30% of Romanians perform such voluntary actions. The percentage increases to 66% for those who claim to be members of a civil society organization. Credit unions, cooperatives and religious associations remain dominant, but of all those working as volunteers, a large number is attracted also by humanitarian organizations and organizations for the environment, ecology, animal rights, as shown in Fig. 7.

|

Fig. 7 – Volunteering |

|

| Click pe imagine pentru mărire |

Volunteering (measured as a percentage of those who are members of organizations) highlights some regional differences that are due to be mentioned. It is one of the few variables that reveals inconsistency at the level of the development regions. Thus, the regions that record values below the national average are the North West region (-8%) and especially the Center region (-17%). A larger number of citizens who participate as volunteers in various associative structures are recorded in the South-East (+6%), North East (+5%) and Bucharest-Ilfov (+5%) regions, but the differences compared with the national average are not significant.

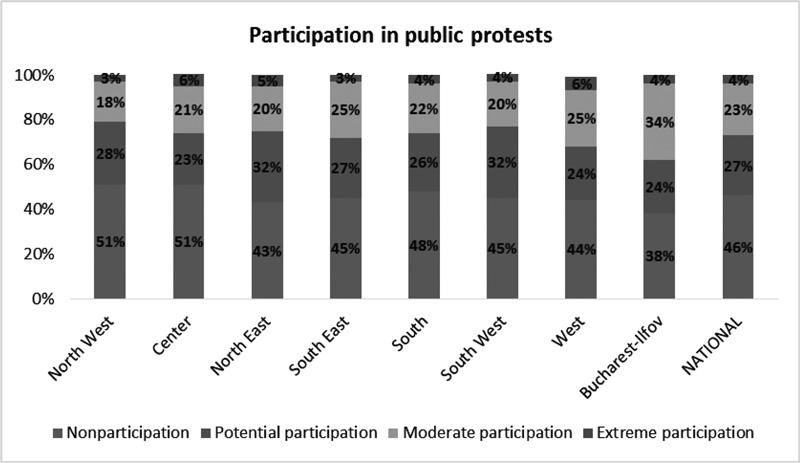

A more visible form of civic activism, with a greater public impact, most often focusing on aspects of the governed-governors relationship, involve taking part in protests. In general, the protest is a tool to which the citizens resort as a last solution, when they are ignored by the decision makers or they do not have access to other channels of influencing the decisions regarding the community.[42] However, the „peaceful protests are increasingly used by younger and more educated citizens“, for whom this form of participation is „the continuation of <normal> policies by other ways“[43].

As it can be seen in Fig. 8, almost half of Romanians (46%) did not attend in protest actions, but some (27%) are willing to do. The other 27% who have assumed such a demarche in the public space, took particularly part in moderate forms of protest, such as signing a petition or legal demonstrations. Extreme participation (illegal strikes, occupation of buildings) is met only in 3% of respondents. Although in recent years the Romanian society has known many moments of protest participation, some of them with direct political consequences,[44] this way of assuming citizenship is the preserve of the urban area (in particular, large urban areas) and of a minority category of the public, made up mainly of young activists, educated above average, with an European identity and a sharper sense of their civic skills.

|

Fig. 8 – Protest participation |

|

| Click pe imagine pentru mărire |

Regarding the distribution by regions of participation in protest actions, a greater passivity in North West and Centre regions is noticed, and a slightly higher civic activism in the West and Bucharest-Ilfov regions. In light of its status as a political and administrative center, the Capital has a tradition of participation in protests, but beyond this specific, the development regions are quite compact and undifferentiated.

Table 1. Values

|

For each of the following, indicate how important it is in your life (% very important + important) |

North West |

Center |

North East |

South East |

South |

South West |

West |

Bucharest-Ilfov |

NATIONAL |

|

Family |

100% |

99% |

100% |

100% |

99% |

99% |

100% |

99% |

99% |

|

Work |

95% |

95% |

95% |

95% |

95% |

95% |

94% |

93% |

95% |

|

Leisure time |

88% |

87% |

85% |

89% |

85% |

88% |

84% |

90% |

87% |

|

Religion |

86% |

84% |

89% |

80% |

85% |

84% |

87% |

76% |

84% |

|

Friends and acquaintances |

84% |

86% |

82% |

83% |

81% |

81% |

81% |

84% |

83% |

|

Politics |

18% |

22% |

24% |

25% |

26% |

24% |

23% |

27% |

24% |

Values are the expression of the interests, preferences, needs and concerns specific to the individuals, members of the community. They provide the foundation for any approach in the public space and structure the social relations, from the inter-personal relations to the political-institutional relations. In other words, the dominant values at the level of a Community act as a factor that regulates and directs the actions of the social actors. Thus, religiosity, or an emphasis on family and work are traditionalism indicators (passive, uncritical orientation in relation to authority), while the interest in politics or the valuation of spare time offer greater premises for civic activism, information and understanding of the events in the political sphere, as well as for participation in public life.

As it can be seen in Table 1, work and family are considered important by almost all respondents, regardless of region. Religion also occupies an important place in the lives of most Romanians, with higher values (above the national average) in the North East region and lower values in Bucharest-Ilfov region. Politics is important for 24% of Romanian, the only significant deviation from the national average being recorded in the North West region. Basically, with a hierarchy of priorities/ preferences wherein the family, work, spare time, religion and friends are important and very important for most of the respondents, without major differences between regions, the Romanian society is rather a traditional type society. This is confirmed by the data revealing the institutional trust (Table 2).

Table 2. Confidence in institutions

|

How much do you trust the following institutions? (% much + very much) |

North West |

Center |

North East |

South East |

South |

South West |

West |

Bucharest-Ilfov |

NATIONAL |

|

The Church |

78% |

72% |

83% |

73% |

77% |

75% |

79% |

67% |

76% |

|

The armed forces |

71% |

66% |

76% |

72% |

73% |

77% |

69% |

70% |

72% |

|

The town hall |

49% |

53% |

51% |

46% |

54% |

56% |

49% |

43% |

50% |

|

The European Union |

47% |

45% |

47% |

47% |

44% |

53% |

49% |

46% |

47% |

|

The police |

48% |

45% |

46% |

44% |

40% |

47% |

45% |

39% |

44% |

|

The press |

40% |

35% |

41% |

39% |

38% |

44% |

39% |

38% |

40% |

|

The justice |

33% |

29% |

36% |

34% |

36% |

35% |

31% |

32% |

34% |

|

NGOs |

33% |

33% |

36% |

34% |

29% |

34% |

32% |

36% |

33% |

|

Banks |

33% |

29% |

34% |

29% |

29% |

33% |

27% |

26% |

30% |

|

IMF |

25% |

24% |

25% |

24% |

24% |

26% |

23% |

20% |

24% |

|

Labor unions |

22% |

17% |

25% |

22% |

21% |

27% |

21% |

19% |

22% |

|

The presidency |

21% |

16% |

19% |

19% |

20% |

19% |

16% |

21% |

19% |

|

The (central) government |

13% |

12% |

17% |

17% |

17% |

20% |

17% |

18% |

16% |

|

The parliament |

13% |

11% |

16% |

13% |

14% |

16% |

10% |

14% |

13% |

|

Political parties |

12% |

7% |

12% |

12% |

12% |

11% |

11% |

10% |

11% |

The fact that the traditional institutions, characterized by strict hierarchy, centralization and directive type management, like the church and the army, enjoy the highest trust does not represent a surprise. The two institutions steadily occupy leading position in confidence among Romanians over the last twenty-five years, even though in the last period they experienced a rebound (especially true for the church). A higher degree of confidence (above the national average) occurs in the North East region (church and army) and the Southwest region (army). It is to be noted that even where the church and the army record lower values, such as in the Center and Bucharest-Ilfov regions,[45] the two institutions remain in the top of the hierarchy.

The central political institutions, the ones that give consistency to the democratic process, fall in the bottom of the table, they being credited with the lowest levels of trust. Also in this case, the regional differences are minor. Likewise, NGOs and the media are trusted by less than half of the population.

The overall picture given by this data is dominated by Romanians’ trust in traditional institutions and by the homogeneity of society. Virtually, there is no region where the top institutional trust to be reversed.

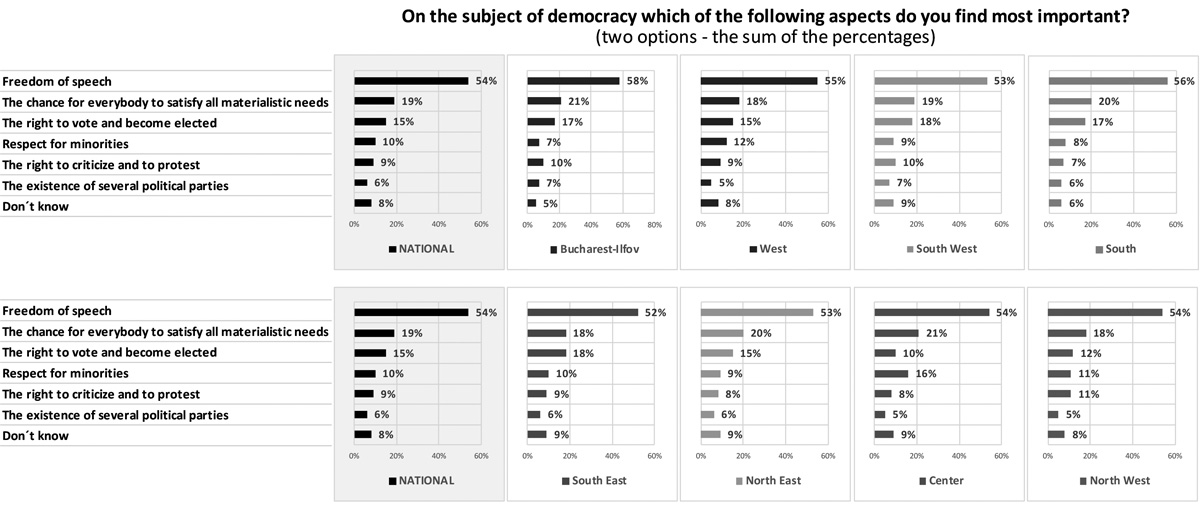

A similar situation is encountered in terms of relation to democracy (Fig. 9 and 10), a variable that also reveals the uniformity of the development regions in Romania. Thus, the majority of Romanians (54%) believe that freedom of speech is the main feature of democracy. This is followed at a great distance, by the social dimension of democracy (the possibility for everyone to be able to satisfy their material needs – 19%) and by the elective dimension (the opportunity to elect and to be elected – 15%). The pluripartidism (the principle of many parties) is considered important to a democratic system by 6% of respondents. Although freedom of expression is strongest capitalized (above the national average) in the Bucharest-Ilfov region, and the respect for minorities is more pronounced in the Center region, it being considered more important than the electoral rights, the regional differences are insignificant.

|

Fig. 9 – Relation to democracy |

|

| Click pe imagine pentru mărire |

|

Fig. 10 Relation to democracy |

|

| Click pe imagine pentru mărire |

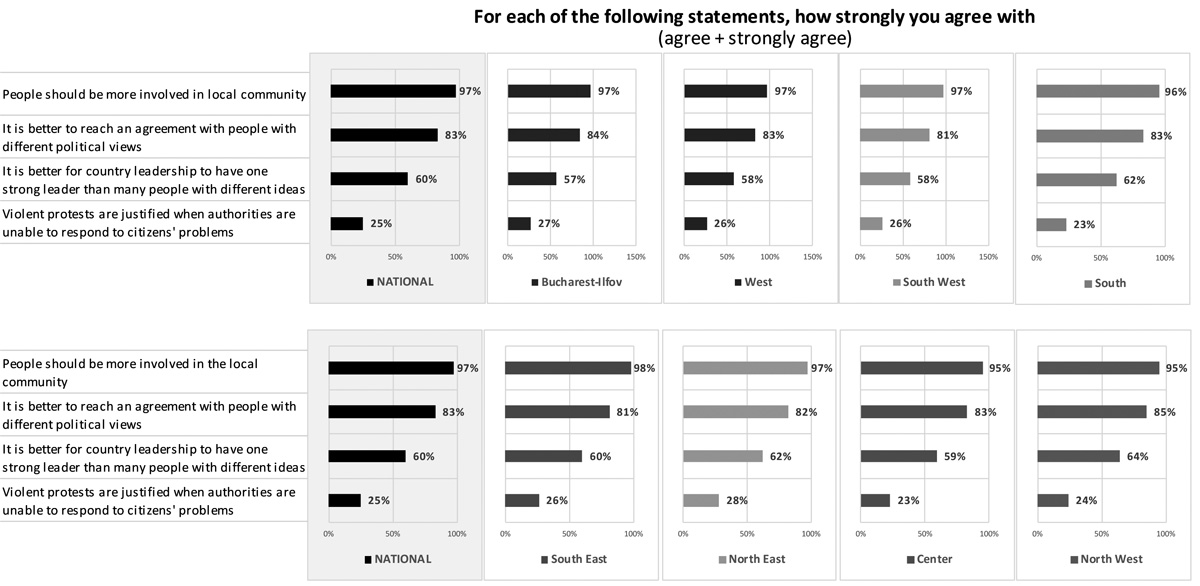

Besides the almost monolithic specific of the Romanian society regarding the political attitudes, behaviors, and values, the sociological data (Fig. 10) reveal the existence of conflicting views about democracy. Thus, the vast majority of citizens value freedom of expression, believes in the social involvement of community members, even if this means a rather discursive adhesion to a desirable behavior, and agrees that democracy requires consensus. Meanwhile, 60% of respondents prefer an authoritarian leader instead of a plurality leadership, this option being slightly more pronounced in the North West. Also, most of the citizens are dissatisfied with the way democracy is evolving in Romania (45% – rather less satisfied, 38% – very dissatisfied).

|

Fig. 11 – Civic competence |

|

| Click pe imagine pentru mărire |

The civic competence is an important dimension of political culture, as it targets the ability of individuals to exercise political influence. A high civic competence does not necessarily imply a permanent action, individually or collectively, in order to influence the political or administrative act. Essential in this regard is the awareness of the community members of their status and role of citizens, of their rights and their responsibilities, of their relationship with authority, of the fact that they are able to file claims and require a certain type of response from the policymakers.

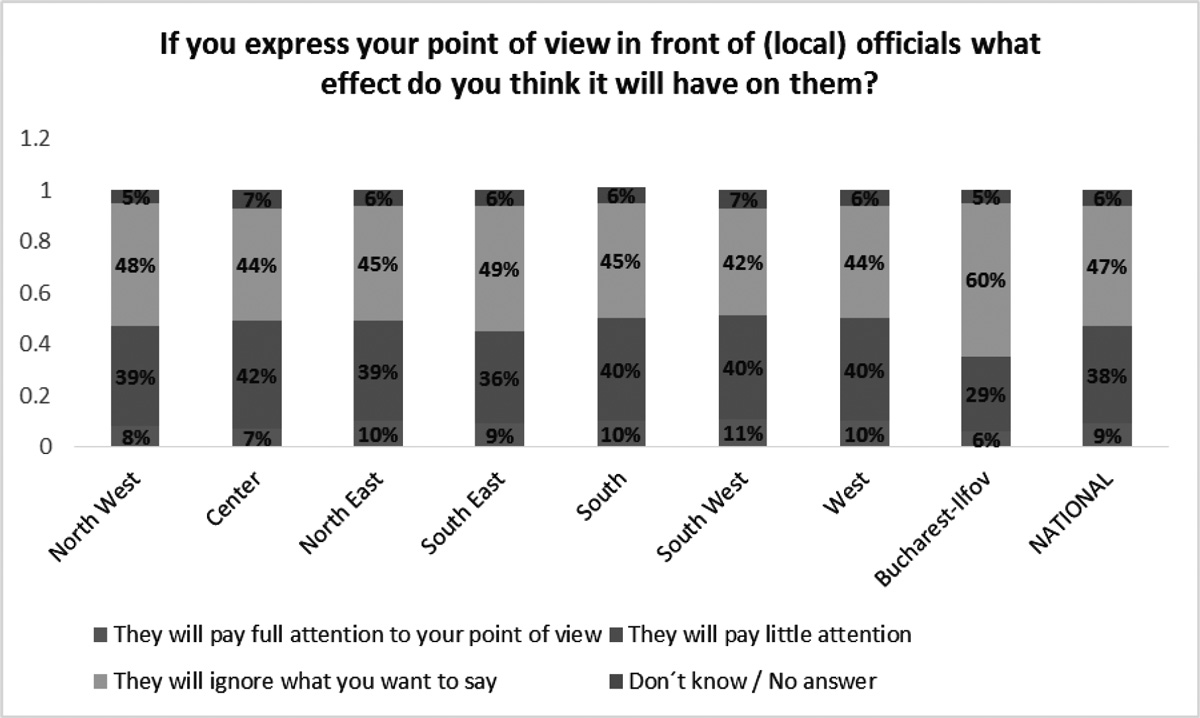

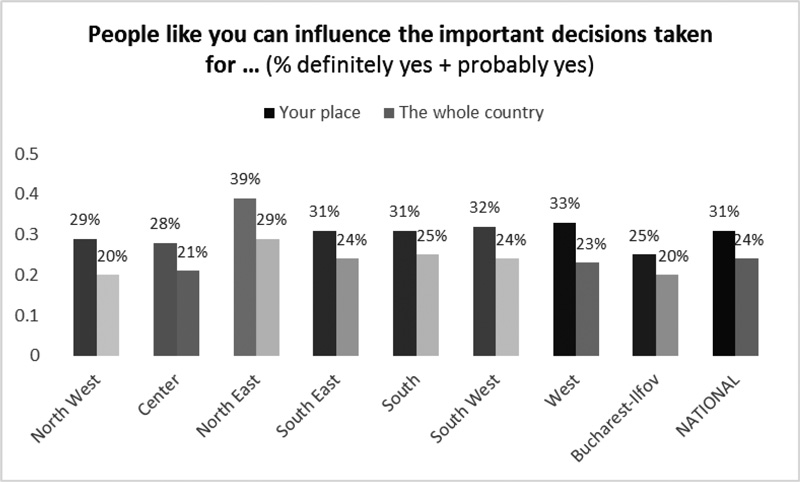

In the case of the Romanian society, the figures speak for themselves (Fig. 11 and 12): 85% of respondents feel that the local authorities rarely take into account the views of citizens, and 3 out of 4 people feel that they do not have the power to influence the political decisions at national level. Romanians feel closer to the local institutions, which they know better and in which they have more confidence, unlike the central institutions. Even so, almost half of the citizens (47%) are of the opinion that the local authorities will ignore their viewpoints. This belief directly influences the availability of civic participation and implicitly the governed – government relationship. Such a reality knows little regional differences.

|

Fig. 12 – Civic competence |

|

| Click pe imagine pentru mărire |

What is surprising is the low level of civic competence in Bucharest-Ilfov region, where 89% of respondents consider that local authorities ignore or pay little attention to the citizens’ views, and confidence in the ability of community members to influence the decisions of local (25%) or central (20%) decisions are below the national average (31% and 25% respectively). The more confident in their relation with the policy-makers, be they local or national, are the residents of the North East region. These fine features merely reinforce the idea that the differences between regions are more in nuance than in direction.

Conclusions

Identifying attitudes, behaviors and values specific to a political community is undoubtedly an approach dependent on the conceptual options and methodological assumptions of the researcher. Expressing a heavily disputed area, not free of controversies, searches and paradigmatic redefinition, political culture is a living concept that offers multiple resorts for social research. It remains a powerful concept of organization and approach to political and social life[46], and the Almond and Verba’s classic prospect continues to be a landmark, especially for the societies in Central and Eastern Europe, in the process of democratic consolidation. The „Civic Culture“ is the first systematic attempt to explain the link between the beliefs, feelings and evaluative orientations of the members of a community and the rules guiding the political system. „The work attracted the attention of generations of scholars who have replicated the findings, criticized the conceptualizations, and refined the theory.“[47]

Although the endeavor to frame a community into the typological patterns proposed by Almond is a bidder one, this paper is not intended to this. Its main objective has been not to identify a model of political culture specific for Romanian society, but to demonstrate that this concept has, at least in the case of Romania, a national dimension. This means that we will not meet regional political cultures (sub-cultures), but that we deal with values, political attitudes and behaviors relatively homogeneous at the level of the society as a whole. The existence of a national political culture can be a feature of the post-communist Romania that to individualize it at least regionally, but the relevance of this finding is especially given by its correlation with the classical theory of political culture and implicitly by the confirmation thereof.

The sociological data used for this demonstration are the result of a quantitative survey based study, conducted between November 2011 and April 2012. The option for this research is due primarily regional representativeness of the sample used. Practically, the questionnaire was applied at national level to eight samples representative for the development regions of Romania. The research proposes a complex operationalization of the concept of political culture, but for this analysis we opted only for part of the measured variables, such as: trust in people, social distance, community cohesion, polarization, associativity, volunteering, attending in protests, confidence in institutions, relation to democracy or civic competence.

The results reveal a reality in which the political culture has a high degree of homogeneity at the country level, the differences between regions being insignificant. Thus, the distrust of other members of the community is a generalized one, the tolerance of groups of people and behaviors considered deviant (drug addicts, criminals, homosexuals) is decreased and group cohesion is manifested mainly at the family level, in the broad sense. The Romanians also have a more local identity[48] (they feel more connected to the people in their locality) and their involvement as members or volunteers in the organized civil society takes place mostly in the religious, syndicate or credit unions structures. Moreover, the most trusted institutions are the traditional ones (church and army), whilst family and work are the most important values. Equally, the public participation is quite low (except the electoral one), amid a relatively low level of civic competence and despite the existence of urban islands (especially the large urban areas) which tends to develop a culture of protest. The involvement in public affairs (at a local community level) is valued and appreciated as a desideratum, but it is rarely transposed into action. Romanians have little confidence in the institutions of the representative democracy, but they expect these institutions to solve their problems without putting pressure to get what they want. As for the reporting to democracy, this is associated primarily with the freedom of speech and the need for political consensus, although more than half of the Romanians prefer one determined leader in power.

All these variables which help to define political culture do not register the profound values which differ from a region to another. However, there are nuances and peculiarities concerning the political values, attitudes and behavior that could individualize regions such as Bucharest-Ilfov, West and North East, but the inter-regional differences still remain insignificant. As shown by the sociological data analyzed, Romania is fairly uniform, which sustains the idea of the existence of a national political culture.

References

1. Almond, Gabriel, and Sidney Verba. The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations. Newbury Park: Sage Publications, 1989.

2. Baudouin, Jean. Introducere în sociologia politică [Introduction in Political Sociology], trans. I Iaworski. Timisoara: Amarcord, 1999.

3. Bădescu, Gabriel, and Paul E. Sum. „Historical Legacies, Social Capital and Civil Society: Comparing Romania on a Regional Level.“ Europe-Asia Studies 57, no. 1 (2005): 117-133.

4. Berezin, Mabel. „Politics and Culture: A Less Fissured Terrain.“ Annual Review of Sociology 23, no. 1 (1997): 361-383.

5. Dalton, J. Russell. „Politica comparată: perspective microcomportamentale“ [Comparative Politics: Micro‐Behavioral Perspectives]. In Manual de Știință politică [A New Handbook of Political Science], edited by Robert E. Goodin and Hans-Dieter Klingemann, 300-313. Iasi: Polirom, 2005.

6. Dalton, J. Russell, and Doh Chul Shin. „Reassessing The Civic Culture Model,“ Paper presented at the conference on „Mapping and Tracking Global Value Change“, Center for the Study of Democracy, University of California, Irvine, March 2011.

7. Diamond, Larry. „Introduction: Political Culture and Democracy.“ In Political Culture and Democracy in Developing Countries, edited by Larry Diamond, 1-27, London: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1994.

8. Dâncu, Vasile. „Transilvania – un deficit al sentimentului de apartenență politică“ [Transylvania – A Lack of Sense of Political Affiliation]. Last modified July 30, 2012. http://vasiledancu.blogspot.ro/2012/07/transilvania-un-deficit-al_30.html.

9. Di Palma, Giuseppe. To Craft Democracies: An Essay on Democratic Transitions. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

10. Eckstein, Harry. „A Culturalist Theory of Political Change.“ American Political Science Review 82, no. 3 (1988): 789-804.

11. Formisano, P. Ronald. „The Concept of Political Culture.“ Journal of Interdisciplinary History 31, no. 3 (2001): 393-426.

12. Johnson, James. „Conceptual Problems as Obstacles to Progress in Political Science. Four Decades of Political Culture Research.“ Journal of Theoretical Politics 15, no. 1 (2003): 87-115.

13. Kaase, Max. „Political Culture and Political Consolidation.“ In Government and Markets. Establishing a Democratic Constitutional Order and a Market Economy in Former Socialist Countries, edited by Hendrikus J. Blommestein and Bernard Steunenberg, 71-114, International Studies in Economics and Econometrics 32, Dordrecht: Springer Science+Business Media, 1994.

14. Kuhn, Sebastian. „Unmasking Instrumental Support for Democracy. A New Approach for Measuring the Political Culture of Democracy,“ Paper presented at the 23rd IPSA World Congress of Political Science, Montreal, July 2014.

15. Laitin, D. David. „The Civic Culture at 30’.“ American Political Science Review 89, no. 1 (1995): 168-173.

16. Laitin, D. David, and Aaron Wildavsky. „Political culture and political preferences.“ American Political Science Review 82, no. 2 (1988): 589-597.

17. Mungiu-Pippidi, Alina. Transilvania subiectivă [Subjective Transylvania]. Bucharest: Humanitas, 1999.

18. Mungiu-Pippidi, Alina. Politica după comunism. Structură, cultură și psihologie politică [Politics after Communism: Political Structure, Culture and Psychology]. Bucharest: Humanitas, 2002.

19. Putnam, D. Robert. Making Democracy Work. Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

20. Radu, Alexandru, and Daniel Buti. Statul sunt eu! Participare protestatară vs. democrație reprezentativă în România postcomunistă [I am the State. Protest Participation and Representative Democracy in Post-communist Romania]. Bucharest: Pro Universitaria, 2016.

21. Reese, A. Laura, and Raymond A. Rosenfeld. The Civic Culture of Local Economic Development, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2002.

22. Roper, D. Steven, and Florin Feșnic. „Historical Legacies and Their Impact on Post-Communist Voting Behaviour.“ Europe-Asia Studies 55, no. 1 (2003): 119-131.

23. Rose, Richard, William Mishler, and Christian Haerpfer. Democrația și alternativele ei [Democracy and Its Alternatives], trans. C Păun. Iasi: Institutul European, 2003.

24. Sandu, Dumitru. Spațiul social al tranziției [The Social Space of Transition]. Iasi: Polirom, 1999.

25. Sandu, Dumitru. Sociabilitatea în spațiul dezvoltării: încredere, toleranță și rețele sociale [Sociability within the Development Space: Trust, Tolerance and Social Networks]. Iasi: Polirom, 2003.

26. Voicu, Bogdan and Mălina Voicu (eds.). Valorile românilor: 1993-2006. O perspectivă sociologică [Romanian Values: 1993-2006. A sociological perspective]. Iasi: Institutul European, 2007.

27. Wildavsky, Aaron. „Choosing Preferences by Constructing Institutions: A Cultural Theory of Preference Formation.“ The American Political Science Review 81, no. 1 (1987): 3-22.

NOTE

[1]The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press).

[2]Russell J. Dalton, „Politica comparată: perspective microcomportamentale“ [Comparative Politics: Micro‐Behavioral Perspectives], in Robert E. Goodin, Hans-Dieter Klingemann (eds.), Manual de Știință politică [A New Handbook of Political Science], (Iasi: Polirom, 2005), 300-313.

[3]Gabriel Almond and Sidney Verba, The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations (Newbury Park: Sage Publications, 1989), 13.

[4]Parochial Political Culture is characteristic of traditional societies where the political structure is non-existent and the political-economic-religious roles are diffuse. The Subject Political Culture is especially characteristic of authoritarian political systems where the dominant orientations are the affective type and only toward the output objects. The Participant Political Culture is a democratic culture in which individuals are explicitly and consciously oriented both to the political and administrative process. All three types of political culture do not exist in pure form. They are ideal-types which are not mutually exclusive and in fact can coexist within the same political culture.

[5]They have political information, acting rationally, they are aware of their rights, liberties but also of the responsibilities arising from the status of being a citizen, and they cooperate to achieve common interests. Individuals trust their peers, the institutions and norms as well as their capacity to involve themselves and influence the decisions.

[6]See Giuseppe Di Palma, To Craft Democracies: An Essay on Democratic Transitions (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990); Max Kaase, „Political Culture and Political Consolidation,“ in Hendrikus J. Blommestein and Bernard Steunenberg (eds.), Government and Markets. Establishing a Democratic Constitutional Order and a Market Economy in Former Socialist Countries, (International Studies in Economics and Econometrics 32, Dordrecht: Springer Science+Business Media, 1994), 71-114; David D. Laitin, „The Civic Culture at 30,“ American Political Science Review 89 (1995): 168-173; James Johnson, „Conceptual Problems as Obstacles to Progress in Political Science. Four Decades of Political Culture Research,“ Journal of Theoretical Politics 15 (2003): 87-115; Russel J. Dalton and Doh Chul Shin, „Reassessing The Civic Culture Model“ (paper presented at the conference on „Mapping and Tracking Global Value Change“, Center for the Study of Democracy, University of California, Irvine, March 2011).

[7]Mabel Berezin, „Politics and Culture: A Less Fissured Terrain,“ Annual Review of Sociology 23 (1997): 361-383.

[8]Berezin refers to Harry Eckstein, „A Culturalist Theory of Political Change,“ American Political Science Review 82 (1988): 789-804) and to David D. Laitin and Aaron Wildavsky, „Political culture and political preferences,“ American Political Science Review 82 (1988): 589-597.

[9]Berezin, „Politics and Culture,“ 364-365.

[10]Dalton, „Politica comparată,“ 301-302.

[11]Sebastian Kuhn, „Unmasking Instrumental Support for Democracy. A New Approach for Measuring the Political Culture of Democracy“ (paper presented at the 23rd IPSA World Congress of Political Science, Montreal, July 2014).

[12]Robert D. Putnam, Making Democracy Work. Civic Traditions in Modern Italy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), 159.

[13]The social capital is the stock of relevant values for sociability. In short, it can be defined as a sum of networks and social contacts, i.e. those connections between individuals based on norms of reciprocity and on the trust resulting therefrom – see Putnam, Making Democracy Work, 167-176

[14]The assertion derives from the Wildavsky’s conclusion, which previously remarked that the subject matter of the comparative research in this area is represented rather by cultures, not by countries or, more precisely, by comparing the countries by putting in opposition their combination of cultures. (Aaron Wildavsky, „Choosing Preferences by Constructing Institutions: A Cultural Theory of Preference Formation,“ The American Political Science Review 81 (1987): 3-22).

[15]Larry Diamond, „Introduction: Political Culture and Democracy,“ in Larry Diamond (ed.), Political Culture and Democracy in Developing Countries, (London: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1994), 1-27.

[16]For Reese and Rosenfeld, the (local) civic culture shapes everything, from the government institutions to political regimes and the subsequent public policies. This (local civic culture) is composed of: the structure of the economic development enterprise; locus of power and input arrangements (who has the power and who has access to decisions on development); decision-making styles (involving rational, planning, analysis or evaluation approach, and specific symbols and myths).

[17]The two authors argue that a careful examination of the definitions of „political culture“ shows that it is associated with states or nations.

[18]Laura A. Reese and Raymond A. Rosenfeld, The Civic Culture of Local Economic Development (Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2002), 40-49.

[19]Dalton, „Politica comparată“.

[20]Richard Rose, William Mishler and Christian Haerpfer, Democrația și alternativele ei [Democracy and Its Alternatives], trans. C Păun (Iasi: Institutul European, 2003), 62.

[21]The authors use NDB survey (New Democracies Barometer) conducted during 1993-1994. The sociological instrument is initiated by Paul Lazarsfeld Society in Vienna in 1991, being applied in successive stages, in nine countries: Czech Republic, Poland, Slovenia, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Ukraine and Belarus.

[22]Rose et al., Democrația, 121.

[23]Vasile Dâncu, „Transilvania – un deficit al sentimentului de apartenență politică“ [Transylvania – A Lack of Sense of Political Affiliation], 2012, available at http://vasiledancu.blogspot.ro/2012/07/transilvania-un-deficit-al_30.html, accessed 12 October 2017.

[24]Steven D. Roper and Florin Feșnic, „Historical Legacies and Their Impact on Post-Communist Voting Behaviour,“ Europe-Asia Studies 55 (2003): 119-131.

[25]Alba, Arad, Bihor, Bistrita-Nasaud, Brasov, Caras-Severin, Cluj, Covasna, Harghita, Hunedoara, Maramures, Mures, Satu-Mare, Salaj, Sibiu, Timis.

[26]Gabriel Bădescu and Paul E. Sum, „Historical Legacies, Social Capital and Civil Society: Comparing Romania on a Regional Level,“ Europe-Asia Studies 57 (2005): 117-133.

[27]The hypothesis is supported by the historical argument of the different cultural and political influences that marked the historical regions of Romania: the Central European culture / the Habsburg Empire in the case of Transylvania and the Balkan culture / the Ottoman Empire in the case of the Old Kingdom of Romania.

[28]Alina Mungiu-Pippidi, Transilvania subiectivă [Subjective Transylvania] (Bucharest: Humanitas, 1999), 66-84.

[29]Moldova, Muntenia, Oltenia, Dobrogea, Transylvania, Crisana-Maramures, Banat, Bucharest.

[30]Dumitru Sandu, Spațiul social al tranziției [The Social Space of Transition] (Iasi: Polirom, 1999).

[31]Dumitru Sandu, Sociabilitatea în spațiul dezvoltării: încredere, toleranță și rețele sociale [Sociability within the Development Space: Trust, Tolerance and Social Networks] (Iasi: Polirom, 2003).

[32]Sandu, Spațiul social, 84

[33]Bogdan Voicu and Mălina Voicu (eds.), Valorile românilor: 1993-2006. O perspectivă sociologică [Romanian Values: 1993-2006. A sociological perspective] (Iasi: Institutul European, 2007).

[34]Voicu analyzes the dynamics of value orientations of the Romanians in terms of traditionalism-cultural modernity binomial.

[35]Similar to Sandu, Voicu operates with historical regions.

[36]Bogdan Voicu, „Între tradiție și postmodernitate? O dinamică a orientărilor de valoare în România: 1993-2005“ [Between Tradition and Postmodernity? A Dynamic of Value Orientations in Romania: 1993-2005], in Voicu and Voicu (eds.), Valorile românilor, 303.

[37]It’s about a survey conducted by the Operations Research within the „Initiative for the civil society“ project, co-funded by the European Social Fund through SOP HRD 2007-2013. Each regional survey had a sample of 1,200 adults, interviews being carried out by CATI method. The data were collected between November 2011 and April 2012 and they were aggregated at the national level. The tolerated margin of error for each sample is +/- 2.8%. The results and conclusions of the survey are available (in Romanian) here: www.infopolitic.ro/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Rezultate-sondaje.pdf

[38]The development regions are regional subdivisions, without legal personality, created in 1998 by Law 151/1998. These were constituted by the voluntary association of neighboring counties. Development regions are not administrative-territorial units, but administrative areas that provide a framework for the implementation and evaluation of regional development policy, as well as the collection of statistical data. The 8 development regions of Romania correspond to the NUTS-II divisions of the EU.

[39]Alina Mungiu-Pippidi, Politica după comunism. Structură, cultură și psihologie politică [Politics after Communism: Political Structure, Culture and Psychology] (Bucharest: Humanitas, 2002).

[40]Almond and Verba, The Civic Culture, 357.

[41]This does not exclude possible axiomatic differences between historical regions, but this issue was not aimed by quoted sociological research.

[42]For details on participation in protest see Alexandru Radu and Daniel Buti, Statul sunt eu! Participare protestatară vs. democrație reprezentativă în România postcomunistă [I am the State! Protest Participation vs. Representative Democracy in Post-communist Romania] (Bucharest: Pro Universitaria, 2016).

[43]Jean Baudouin, Introducere în sociologia politică [Introduction in Political Sociology], trans. I Iaworski (Timisoara: Amarcord, 1999), 122.

[44]The fall of the Government led by Prime Minister Emil Boc (March 2012) or of the one led by Prime Minister Victor Ponta (November 2015) occurred as a result of extensive street demonstrations.

[45]Incidentally, in the Centre and Bucharest-Ilfov regions, most of the „minimums“ (percentages below the national average) of trust in institutions are recorded.

[46]Ronald P. Formisano, „The Concept of Political Culture,“ Journal of Interdisciplinary History 31 (2001): 424.

[47]Laitin, „The Civic Culture,“ 168.

[48]However, there are small differences in the North-West region where there is a slight regional orientation, and in Bucharest-Ilfov region, with a greater national identity.