|

Politică și societate

Just how tabloidized is tabloid press?

Personalization, sensationalism and negativism in the

coverage

of the Romanian presidential elections, 2009

FLORINA CREŢU1

[National School of

Political and Administrative Science]

Abstract:

The problematics of the public sphere, as

firstly outlined by Habermas, has triggered many

reflections concerning the metamorphoses in

political communication. In this regard, one of the

most prominent phenomenona approached in the

established literature of media transformations

refers to that of tabloidization. According to

different scholars, not only are journalistic

discourses heading towards a tabloidized style of

reporting, but also these practices tend to hinder

the creation of public spheres. The present study

wishes to understand the relation between these two

assertions and empirically, to test their validity

on the Romanian tabloid media. Particularly, it aims

at exploring whether the tabloids’ news coverage of

the last presidential elections meets the general

standards of what is called „tabloidization”; and if

so, how this may affect our definitions of the

public sphere.

Keywords: trends in political communication;

personalization and sensationalism of tabloid

discourses; negative reporting; Romanian tabloid

media

1. Introduction: the public sphere and the page 5

syndrome

Habermas’ first work on the public sphere and „the

commodification” of the public realm2

has initiated different perspectives, concerning both the meanings of this

concept3 and the transformations

it signaled4.

The commercialization of political communication, as this process has broadly

been coined by scholars, has been the subject of ample research and was given

many names in the established literature. From „Americanization”5

to „mediacracy”6 and

„tabloidization”7academics have

tried to designate, one way or another, the changes occurring in the media

coverage of political events. Generally, they referred to an allegedly growing

journalistic style that values sensationalist discourses, a particular focus on

the personality of politicians, as opposed to policies or political programs,

and a negative trend of reporting. Supposedly, this would result in citizens’

apathy towards politics8, a

general „dumbing down”9 and the

dissolution of certain democratic values, as we know them.

The overwhelmingly pessimistic view over these changes in political

communication has developed to the extent where different journalistic genres

were classified as being or not part of the public sphere10.

This was particularly the case of tabloid and tabloidized media, considered idle

for everyday opinion formation, through their playful and brief style of

reporting11. We find this type

of approach not only sterile in our understanding of media dynamics, but also

narrow, in what regards the definitions of tabloidization and the public sphere,

generally. How can these concepts be defined? Is there a general

trend of tabloidization? And if so, does this necessarily involve a

dissolution of the public sphere? These questions will represent the

landmarks of this paper. However, answering them requires a deeper understanding

of the broader context they stem from, that of mass-media commercialization and

its associated processes. Thus, the next section of this study will try to

address this issue.

2. The mediated public sphere: structural transformations in political

communication

The public realm’s colonization by the entertainment industry

represented one of the first statements that defined both the transformations

occurring in the public sphere and the eloignment from its normative ideal.

Thus, originally, the public sphere was understood as „the sphere of the

individuals that gather as a public”12,

a rational, deliberative space of engagement between citizens and public

authorities, designed to reach the common good. According to Habermas13,

the current public sphere, represented by political journalism, lacks a certain

sense of rationality, sobriety, objectivity and deliberative potential.

Generally, this approach of the evolution of political communication has

generated endless debates concerning the media’s role in contemporary

democracies, and especially that of television. Although the various points of

view expressed in this regard stress on distinct perspectives, they converge in

the following postulate: because the media represent our main sources of

information and interaction with the political world, they represent the public

sphere. In this context, they are seen as placing themselves in the center

of political processes, shaping the public agenda14

and even the practices of political institutions15,

generating what is called a „mediated public sphere”16.

Thus, some authors have taken the Habermasian stand, affirming that by using

sensationalist discourses, influenced by popular culture elements, the quality

of modern journalism has seriously diminished17.

Allegedly, the result of this would be the decline of civic involvement18

and the rise of political cynism19.

Before we proceed at discussing the effects of the „new political

communication” upon citizens, we deem necessary to highlight the way

commercialization is understood in the light of the abovementioned theories.

Thus, this phenomenon is considered a product of two different processes:

first of all, under the pressures of market imperatives, the birth and

development of private televisions, media instances have started to include in

their programming an increasing number of entertainment shows20.

That is why various scholars have ascertained the emergence of journalistic

genres tributary to popular culture like talk-shows, lifestyle magazine

television and those pursuing private experiences, testimonials. In this

context, authors like Adorno, Horkheimer21

and Mehl22 speak of a culture

of commodification and emotions that would lead to a dissolution of the

boundaries between the public and the private.

Secondly, different formats of political communication have started to borrow

entertainment elements, generating what is called infotainment23.

As Van Santen has shown, this term has been interchangeably used with that of

„tabloidization”24. The

dominant outlook over this trend is that topics such as fashion, sporting events

and sensationalist facts dominate the media agenda, to the detriment of

political issues. Furthermore, it is deemed that throughout electoral campaigns,

political candidates have started to conform to this media logic, promoting

their image in certain genres considered until recently non-political, such as

talk-shows or in various informal contexts (shopping, playing the saxophone,

dancing, etc.)25. This process

is referred as the depolitization of political communication26.

One of the principles of this strand of literature is that modern press

provides over-simplified information to the public regarding politics (the so

called „dumbing-down” effect)27,

stressing rather on the visual component of political communication and

generating what is currently called image-bite politics28.

In other words, the idea underlining this approach is that the political

information we ordinarily receive is reduced to a fast collage of candidate’s

pictures.

Moreover, media coverage of electoral campaigns is said to be increasingly

focused on designating winners and losers, engendering a pretended

horse-race coverage29.

Last but not least, by stressing on the personal lives of politicians and

weighing against their political programs, mediated discourses embolden the

personalization of politics30.

All these phenomena have been broadly ascribed to a trend of Americanization

in political communication31.

Consequently, the various transformations occurring in political journalism have

been associated to terms such as „mediacracy”, „spectatorship” or „public

relations democracy”32.

Thus, the view underlined by this perspective is the following: the mediated

public sphere represents a space of journalistic problematization that should

cultivate a rational outlook over political realities, in the detriment of an

emotional or a playful one. Supposedly, it should also value a certain formalism

in representing the political world, by stressing on its informational content,

residing in punctual data about legislative measures and electoral platforms.

Thus, one of the standards of political journalism is deemed as making citizens

more interested and informed concerning politics. Otherwise, the possibility of

fostering an authentic mediated public sphere is seen as questionable, and the

only reflex it may generate among citizens is considered to be cynism or

consumerism33.

Obviously, this evaluation of the metamorphoses in political communication has

been perceived by many academics as quasi-fatalist and sterile as regards to

understanding these processes34.

First and foremost, due to the particularities of each media culture, one cannot

speak of a common degree of commercialization of public spheres. From this

perspective, in his study of the television programming during the electoral

campaign in 1994, Brants concluded that the proportion between information-based

shows and entertainment ones was somewhat balanced35.

Another finding of his research was that throughout the campaign, the candidates

turned rather to informative genres such as newscast and current affairs, unlike

the tendency described by other studies.

Hence, analyzing the changes occurring in political communication requires a

more nuanced interpretation of the commercialization phenomenon, considering

also the different cultural variables at play. From this reason, the various

trends highlighted so far have been explored rather as research hypotheses in

different intercultural studies36.

As for the effects of this type of political journalism, various authors have

expressed their disagreement about its’ negative influence on everyday political

involvement37. Drawing on the

idea that the changes occurring in political communication also imply both a

different way of engaging in the public life and of understanding participation

itself; they argue for a definition of this concept based on citizens’

discursive activity, interest, attitudes and meaning-making processes,

engendered by watching political shows.

Thus, through their symbiosis with elements of popular culture, genres

containing entertainment elements are seen as having the potential to stimulate

audiences’ interest, who otherwise would reject political information38;

to reduce the social distance between politicians and the electorate39;

inspirit citizen talk40 and

various reflections concerning politics41.

Still, the strength of these effects varies from one public to another,

according to different socio-demographic variables, media consumption patterns

and political interests42.

Furthermore, by using a playful or even ironic or emotional approach, media

discourses may provide their publics another opportunity to critically position

themselves toward communicational contents43

and may represent forms of resistance against dominant social ideologies44.

From this perspective, the mediated public sphere is perceived as a cultural

sphere45, and represents „the

articulation of politics, public and personal, as a contested terrain through

affective (aesthetic and emotional) modes of communication46”.

Thence, it embeds popular culture’s and entertainment’s various forms of

manifestation, that provide for a space of reflection both regarding the inner

and outer world; allow for a certain sense of identification (like in the case

of soap-opera characters and their public) and the dialogue with our surrounding

ones.

Thus, the multiple transformations in political communication are understood

and evaluated very distinctly in the established literature. Some views have

signaled the existence of a pseudo-public sphere, of the political journalism

that values emotions in the detriment of rational reflection, the „private” as

opposed to the public and images instead of information. Others have highlighted

the emergence of a cultural public sphere that celebrates particularly these

elements, and whose manifestations contribute to the reconsolidation of the way

in which we understand political participation and even politics nowadays.

Consequently, the different tendencies of „aestheticization”47

and „emotionalization”48 in

the public sphere may have distinct effects, that go beyond the classical

interpretation paradigms of some concepts such as political knowledge.

3. Tabloidisation in the public sphere: drawing the conceptual

framework

As highlighted in the previous part of this paper, the

commercialization phenomenon has been associated with different processes and

designations. Among these, the issue of tabloidization stands as one of the most

prominent, due to its all-encompassing conceptual nature. Thus, this particular

notion is often connected with all of the abovementioned transformations in

political communication, such as depolitization, sensationalism,

personalization, horse-race coverage or focus on popular culture elements49.

Hence, it has reached a certain conceptual ambiguity, consolidated also by its

frequent association with broad terms such as „politics as entertainment”50

and its interchangeable use with that of infotainment51.

Nonetheless, some themes remain consistent, which will the subject of our

personal understanding of the concept.

In the established literature, there seems to be a certain assent regarding

the fact that tabloidization is a product of one or more of the following

dimension: a negative reporting of politicians, meant to attract the public’s

attention52; a focus on

sensationalist, entertainment-based discourses illustrating unusual events from

the political world53; a

particular emphasis on candidates’ private lives or personal character, as

opposed to public policies or electoral platforms54.

Furthermore, this type of focus on the private persona is also

illustrated by the increasing use of visuals to the detriment of informational

content55.

Thus, tabloidization is deemed as the cause of trends such as negative

coverage (or negativism), sensationalism and

personalization (or individualization) in political communication.

Furthermore, it is perceived as an expanding phenomenon, threatening the quality

of political journalism, the integrity of public culture, political involvement

and the health of democratic processes, generally56.

The pessimistic approach over this alleged orientation of mediated discourses

raises a number of questions: Is the nature of these effects indisputable?

Or, in other words, do they necessarily imply a decline of public

participation and interest in political affairs?

Although throughout the literature the connotations of tabloidization remain

mostly negative, some academics have argued for a more open-ended perspective

over this concept. Instead of referring to the benefits of classical journalism,

as a terrain of the authentic public sphere, different authors claim that, in

fact, tabloid media may represent an alternative, subversive public sphere57.

The emphasis laid on private experiences could represent the proof of more

„deeper cultural concerns”58;

their playful style of reporting and topics could be a form of challenging

dominant ideologies59 and a

way to achieve „a greater imaginative proximity to the lifeworld of the

audience”60.

Whatever the angle we might chose to adopt in evaluating this phenomenon, its

evaluation requires firstly that we investigate its degree of prominence in

certain media contexts. Otherwise, we might be evaluating a binary, distorted

picture of reality that is less grounded in our everyday media landscape. In

other words: Is tabloidization a rising process, as presumed by some61?

Like Esser62, we argue that

any answer to this question will need to take into account the different

cultural variables at play, such as the media culture within which journalistic

discourses unfold and the organizational particularities of each media

institution. Thus, one of the assumptions that will guide the forthcoming

empirical undertaking is that each media landscape is marked by different

degrees of tabloidization, if the presence of such a trend is observed.

So far, this phenomenon has been the subject of consistent research carried

out in the United States63,

Western Europe64, different

studies in China65 and The

Third World66. However,

studies in commercialization and, particularly, tabloidization in Central and

Eastern Europe remain to a certain extent scarce, being limited to a small

number of studies67.

Particularly in the case of emerging democracies in East Central Europe,

where private media institutions have developed later than those in the West,

the patterns of what one might call „tabloidization” could be less prominent.

This assumption is also justified by the views according to which, unlike the

American media outlets, some European media institutions have shown a certain

„resistance” to commercialization68.

One of the peculiarities in the study of the tabloidization hypothesis is

that it has mostly been explored by analyzing the tone and narratives of

„quality”, televised journalism69,

and to a lesser extent the style of tabloids themselves70.

Thence, paradoxically, its implicit premises have somewhat been taken for

granted in the case of „yellow journalism”. We contend that analyzing the

degree of tabloidization in a certain media culture should also

consider this aspect, as it would provide for richer, culturally valid

interpretations of this concept. For example, tabloids in Bulgaria seem to

focus on public issues, whereas the „quality” media are deemed as growing

sources of personal, sensationalist narratives71.

Hence, the idea of tabloidization may need different tinges and ways of

designating it.

Having in mind also the hypothesis of commercialization resistance in Europe72

and the potential variability of tabloidization in the Eastern bloc, this

research will pursue the following question: Is tabloid press nowadays

strongly tabloidized? Answering this question requires that we underscore

our empirical focus and personal interpretation of the phenomenon, which is what

the next section will highlight.

4. Methodological benchmarks

As previously outlined, very little research has examined the

tabloidization hypothesis in Eastern Europe. Particularly in the Romanian media

landscape, where this question has become more prominent in the last years73,

only one study has approached this particular phenomenon74.

However, it considers only the style of televised, televised sports news. Thus,

Romanian tabloids’ degree of tabloidization remains an unresearched topic.

The subject of this empirical demarche is represented by the coverage of the

last Romanian presidential campaign, in 2009. This choice was founded not only

by the postulate that electoral campaigns are increasingly tabloidized75,

but also by the fact that this particular political moment has been highly

controversial. Thus, in this campaign the acts of violence between various

groups of party members have held the news agenda for some time76;

verbal attacks of some political leaders have been often broadcasted; current

president and candidate for the position, Traian Băsescu, has been accused of

hitting a child during an electoral meeting; and the party supporting him became

famous after using in their promoting strategy local oriental songs (“manele”)

with a strongly negative reputation in the mainstream intelligentsia. Last but

not least, Băsescu’s mother suffered a surgical intervention for breast cancer,

and his daughter was said to soon announce her wedding77.

Having this type of issues on the media agenda of the 2009 campaign, we

expected that the local tabloids exploited some of them more than classical

political topics (such as electoral programmes or current internal issues).

Thus, one of the hypotheses of this research was that in these

particular circumstances, the tabloids’ coverage of the 2009 campaign might

have been the subject of a high degree of tabloidization. Before we proceed

with outlining our personal understanding of the concept and how such an

assumption could be tested, we will further detail the focus of this empirical

study.

Because Traian Băsescu, as current president at that time, and both his party

and family were frequently mentioned in the media discourses of the last

campaign, their portrayal in the tabloid press will constitute the center of our

research. By using the content analysis of references in online articles in

the period starting from the pre-campaign to the elections; we tried to

explore the extent to which the tabloids’ coverage of these actors was

marked by negativism, personalization and sensationalism. A special

emphasis was laid on how this particular candidate was illustrated in connection

to his family, party members, campaign events and issues of the current

government.

By searching for the key-words „Traian Băsescu” and „PD-L” (the supporting

Democrat-Liberal party) in the archives of the three most visited online

tabloids in 2009, we first tried to explore the main themes associated to this

candidate. The identities of these papers and the reasons that lead to their

choice will be further exposed below. Thus, in the period between October 1st (2

weeks before the official beginning of the electoral campaign) and December 5th

(the end of the campaign), we identified 394 articles corresponding to our

criteria.

Because the period of the electoral campaign was marked by a number of

outstanding events; such as the economic crisis, the cut-backs in public

functionaries’ wages, union strikes and political conflicts, they appeared in

the coverage of Traian Băsescu, as current president.

Overall, the main themes associated to this candidate were excerpted

inductively and designated as follows: deficits of the present government; the

candidacy of Băsescu and campaign events carried out by his party; his family;

the electoral debates; and the alleged aggression of a child. The first meaning

cluster (“deficits of the present government”), represented a resulting category

of 4 sub-themes, which were identified as: political conflicts or political

crisis; strikes, public functionaries’ wage reduction or economical crisis;

economical and political crisis; accusations of corruption. Thus, these themes

were coded in SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) and their

prominence was assessed by means of frequency measurements and crosstabulations.

As the research understood tabloidization as a product of personalization,

sensationalism and negativism, we tried to explore the degree to which each of

these processes exist in the tabloids’ coverage of Traian Băsescu. Thus, our

underlining hypotheses interpreted these concepts as follows:

RH1. If the references concerning Băsescu’s

allegedly hitting of a child outnumber those concerning

his campaign events, candidature or presidential position (deficits of the

government), than the tabloids are a subject of a high degree of

sensationalism.

Thus, the assessment of this hypothesis considered only the period in which

this particular event occurred; and is based on the often-mentioned postulate

according to which tabloid formats favor spectacular events to the detriment of

public issues or the electoral process itself78.

RH2. If the frequency of references

concerning the candidate’s family is higher than that of the mentions

regarding his image as a candidate (campaign events) or as the

president (issues of the government), then we can speak of a high degree of

personalization. The assumption is also confirmed if most of the articles

contain pictures of the candidate.

The formulation of this premise envisaged the plea according to which

campaigns in the age of tabloidization focus extensively on the personal lives

of politicians and on the visuals portraying these individuals79.

RH3. The presence of negativism in the tabloids’

coverage of Băsescu is confirmed if the overall tone of the most articles is

unfavorable concerning: him as a candidate (candidacy and campaign events; in

the televised debates); as the person potentially hitting the child; his family;

his image as the current president (deficits of current government).

This hypothesis was built considering not only the alleged negative trend in

the coverage of politicians80,

but also the fact that some members of this candidate’s family have a rather

unfavorable image in the Romanian landscape. Thus, his youngest daughter was

accused of unrightfully occupying a high a position in a local private company,

earning an unusual high income for it81

and owing her political career to Traian Băsescu. Furthermore, the

abovementioned inference took into consideration the fact that the political and

social events happening before and throughout the campaign were most likely to

be attributed to the president.

The sheets subject to our analysis were chosen according the highest ranked

tabloids as number of visualizations in October and November, 200982.

Thus, Libertatea („Freedom”) occupied the first position, Cancan was the second

most viewed and Click represented the third. However, as Click did not have a

database of its previous articles, we proceeded to the next ranked tabloid as

number of displays, Showbiz.ro. Because this sheet also did not own a personal

archive of articles, we used the one provided by its host website and brand

owner, Apropo.ro.

Naturally, because any media institution has a distinct broadcasting identity,

underlining values and ownership, our methodological undertaking also

acknowledged the particularities of each online tabloid. Thus, the aforesaid

hypotheses were tested also on every one of these papers, in order to have a

clearer view over our findings.

5. Findings of the research

5.1. Sensationalism

In what concerns our first hypothesis, that of sensationalism understood as

the tabloids’ focus on Băsescu’s alleged violence act, it proved to be false.

The event started to be mentioned as of November 27th until December 5th and in

this time range it had only 22 references of the total 66 related to this

politician (SD=0.63). Consequently, its degree of coverage was lower than that

of the candidate’s campaign events and presidential image, associated with

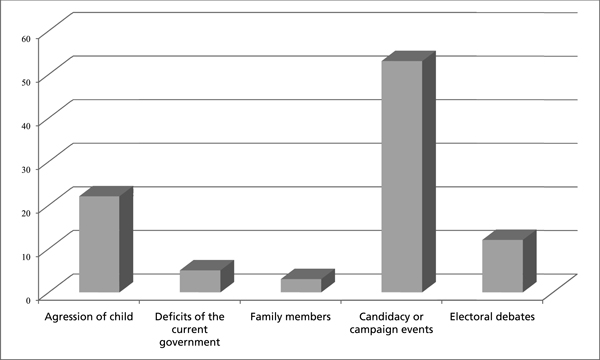

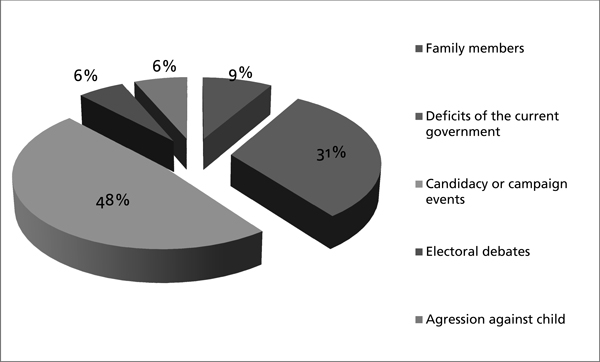

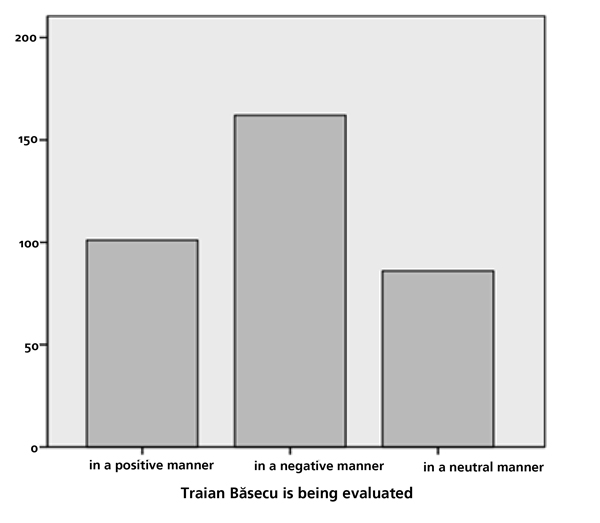

various deficits of the government (fig.1).

Fig.1. Overall distribution of

themes associated to Traian Băsescu, November 27th-December 5th

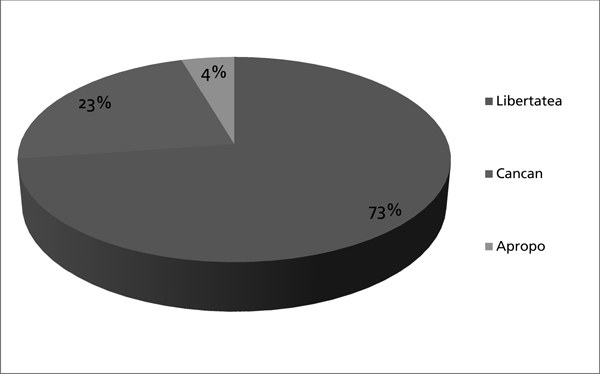

Fig.2. Distribution of references

within each tabloid concerning Băsescu’s act of violence

Fig.3. Libertatea: distribution of

themes associated to Traian Băsescu, November 27th-December 5th

Nonetheless, some of the campaign events themselves might have represented a

source of sensationalism, since they illustrated the clashes between different

party members, the oriental songs used for promoting Băsescu and the various

attacks addressed to this candidate. Still, in the abovementioned time range,

this category also included news referring to the opposition’s plans for the new

government and the incumbent’s course of action if he lost the election. Thus,

overall, the hypothesis according to which Băsescu’s coverage was marked by a

high degree of sensationalism, turned to be incorrect. However, its evaluation

requires that we also consider how each of the tabloids reported this event.

As figure 2 shows, the sheet that mentioned it most frequently was Libertatea,

followed by Cancan and Apropo (x2(6, N = 66) = 1.386, p < .05). This

particular sheet dedicated only 34,8% of its total references to Traian Băsescu

in this time range concerning his alleged aggression of a child (N=46; SD=0.68).

The majority of the articles focused on the campaign events, electoral debates,

deficits of the current government and family members, as illustrated in figure

3.

As for the other two online sheets, Cancan dedicated to this subject 29.4% of

its total references (N=17; SD=0.47) and Apropo, 33.4% (N=3; SD= 0.57). Both

followed the overall theme distribution as Libertatea, but without mentioning

any facts or opinions concerning Băsescu’s family.

Hence, our hypothesis regarding the presence of sensationalism in the

tabloids’ coverage of this candidate was invalidated. Most of their references

approached Traian Băsescu’s campaign events, and not his alleged act of

violence. This trend was also confirmed in the case of each tabloid. Although

the references concerning this potential aggression outnumbered those

illustrating various deficits of the government (the economic crisis, the

cut-backs in public functionaries’ wages, union strikes, political conflicts,

accusations of corruption); we considered it a result of the long period in

which these political and social events had been highly broadcasted. Thus, since

their frequency had already diminished by the time this new controversial issue

appeared, we did not consider this finding relevant to our analysis.

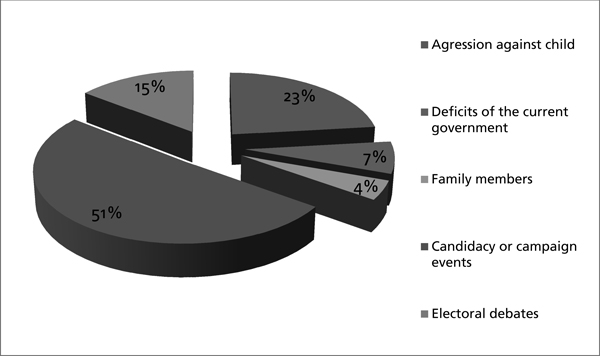

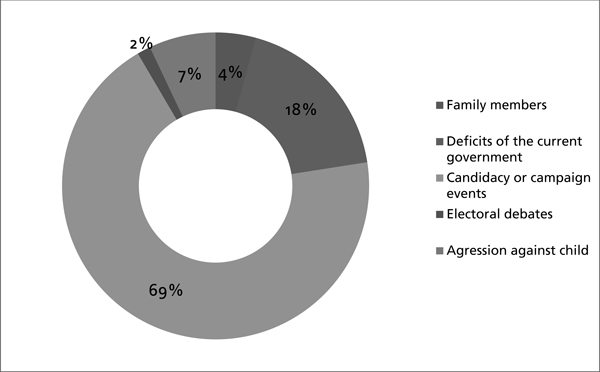

Fig.4. Overall distribution of

references of Traian Băsescu, October 1st – December 5th

Fig.5. Libertatea: distribution of

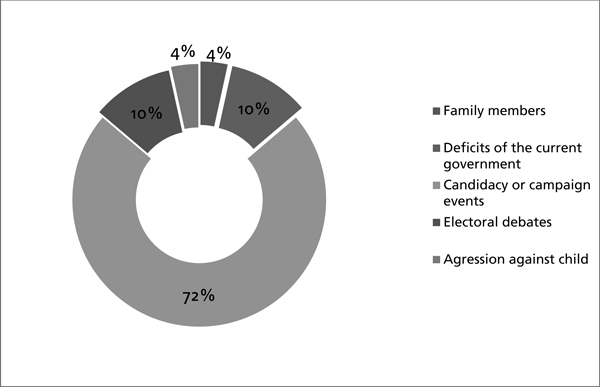

themes associated to Traian Băsescu, October 1st – December 5th

Fig.6. Cancan: distribution of

themes associated to Traian Băsescu, October 1st – December 5th

Fig.7. Apropo: distribution of

themes associated to Traian Băsescu, October 1st – December 5th

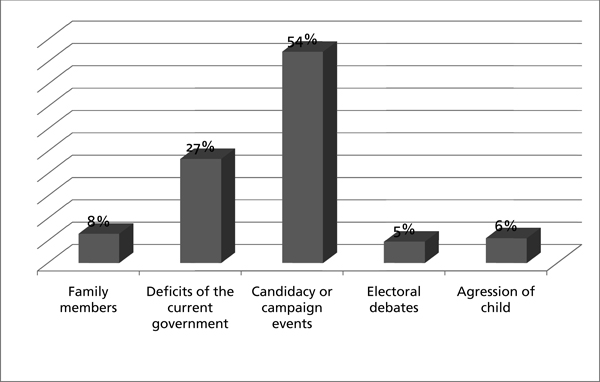

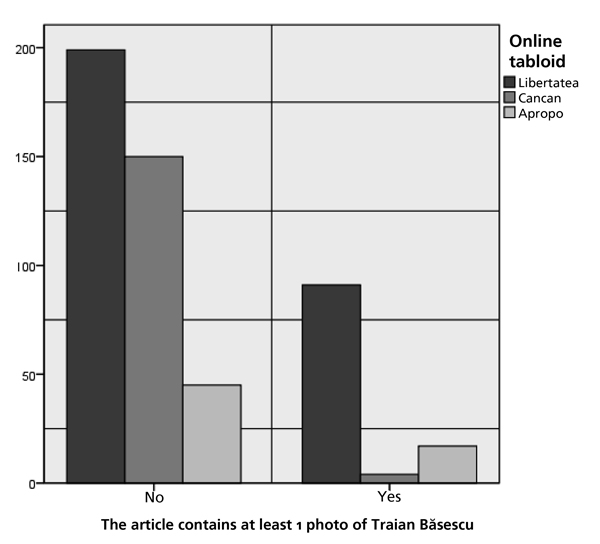

Fig. 8. Presence of images

illustrating Traian Băsescu in each of the three tabloids

5.2. Personalization

The second assumption of our empirical research was that if the frequency of

references concerning the candidate’s family is higher than that of the mentions

regarding his image as a candidate (campaign events) or as the president (issues

of the government); then one can speak of a high degree of personalization in

the tabloid press.

By exploring the candidate’s associations with the categories specified in the

methodological section of this paper, we found that overall, this hypothesis

does not confirm. As shown below, the references about Băsescu’s family amounted

less than those illustrating campaign events or deficits of the government

(N=394). Because their proportion was very low in the overall coverage of the

candidate (8%, N=394; SD=0.4), we considered that there was no particular

emphasis on his private life. Moreover, no other remarks were made about him as

an individual.

Still, we proceeded at assessing the validity of this presumption by analyzing

how each of the tabloids portrayed this candidate. Thus, Libertatea, Cancan and

Apropo have maintained the overall distribution described above, emphasizing on

Băsescu’s campaign events (48%), and associations with the issues of the current

government (31%) (N= 282). As illustrated in figures 1, 2 and 3, the references

about his family remained scarce in the case of each tabloid: Libertatea, 6%

(N=282; SD=0.5); Cancan, 2% (N=73; SD=0.39); Apropo, 4% (N=39; SD=0.16).

Although under the terms of our framework, the hypothesis of personalization

was infirmed, this evaluation can be considered somewhat questionable from a

particular angle. If we consider the higher number of references dedicated to

Traian Băsescu’s family than that of his participation and performance in the

televised debates, then this may represent itself a sign of personalization.

Still, considering the low percentages of both of these themes and the reduced

number of articles provided by Cancan (N=73) and Apropo (N=39), by comparison

with Libertatea (N=282), reaching such a conclusion would need wider samples and

further research.

Fig. 9. Overall distribution of

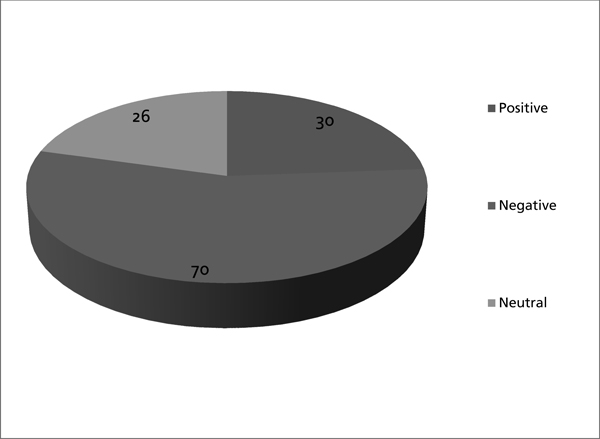

positive, negative and neutral references of Băsescu

Another measure of personalization that we introduced into our analysis

concerned the presence of this candidate’s pictures in most of the articles. As

figure 8 illustrates, no such tendency was observed in all of the three tabloids

(x2(2, N = 394) = 49.491, p < .05).

Apropo included in 43.6 % of its articles pictures illustrating Traian Băsescu

(N=39; SD=0.5), followed by Libertatea, 32.3% (N=282; SD=0.46) and Cancan, 5.5%

(N=73, SD= 0.22). Hence, since none of the tabloids seemed to have dedicated to

pictures an essential part of their coverage, we considered that the

personalization hypothesis was not confirmed in this regard either.

Still, our analysis did not consider the size of the pictures compared to that

of texts, an element often associated with tabloidization (Franklin, 1997;

2008). Nonetheless, under the terms of this research, the personalization

hypothesis does not stand; but would still require an evolutionary approach to

see whether in the past Romanian tabloids have included fewer pictures in their

articles.

5.3. Negativism (negative coverage)

The third main hypothesis of our empirical demarche concerned the presence of

negativism in Traian Băsescu’s coverage. It was assessed by means of the overall

evaluations provided by the three tabloids and specifically considering: him as

a candidate (candidacy and campaign events; in the televised debates); as the

person potentially hitting the child; his family; his image as the current

president (deficits of current government).

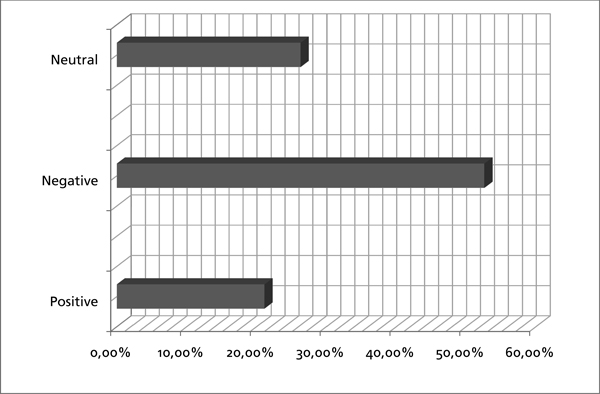

Fig.10. Distribution of positive,

negative and neutral references of Băsescu in each of the tabloids

Our analysis will outline first how the three tabloids presented him overall,

and then will proceed at illustrating how they evaluated him in association with

each of the abovementioned themes.

As figure 9 shows, throughout our period of analysis, it would seem that

Băsescu was overall evaluated in a negative manner (50,6%), and to a lesser

extent in a positive (19,3%) or neutral way (30,1%) (N=394). However, if we were

to divide these categories into negative and non-negative (positive and neutral)

references, our perspective over his evaluation would probably be different.

Thus, we cannot claim that, overall, the assessments of this candidate have been

clearly negative, unless we also explore in what period they occurred and which

of the tabloids might have influenced this overall trend.

The main tabloids who have had negative references concerning this candidate

are Libertatea (36,9%) and Apropo (18,5%) (x2 (6, N = 394) = 69.192, p

< .05). As figure 10 shows, Libertatea was also the sheet that provided most of

the positive and neutral evaluations of Traian Băsescu, due to its high number

of articles compared to the other online tabloids.

Before the official beginning of the electoral campaign, the candidate was

referred at mostly in a negative fashion (37.7%), and to a lesser extent in a

positive (24.7 %) or neutral manner (20.1%) (N=154; SD=0.99). In this interval,

from the sub-themes of what we called „deficits of the current government”, he

mostly received negative references in relation to the theme of strikes, wage

reduction or the economic crisis (13.6%); and to a lower degree with political

conflicts (5.8%) and the idea of corruption (5.2%) (x2 (12, N = 154) = 75.043,

p < .05) Thus, the candidate was framed as the president responsible for

the economic crisis, which is probably why the references concerning his family

were so scarce (5,23%; N=154; SD=0.51).

Fig. 11. Overall evaluation in

connection with campaign events

Furthermore, in this time range, the candidate’s negative evaluations related

to his family represented only 0,29% of all mentions, whilst the positive ones

comprised 1%. We attributed this to the fact that the tabloid with the highest

number of articles, Libertatea, emphasized on the illness of Băsescu’s mother in

a compassionate manner.

In the electoral campaign period, the overall trend of presenting Băsescu was

maintained, mostly negative (43.3%) and to a lesser extent positive (26.3%) or

neutral (22,9%) (N=240; SD=0.87). From the category entitled „deficits of the

current government”, the main topics he was associated negatively with during

this time consist of corruption (6.3%) and strikes, wage reduction or the

economic crisis (5.4%) (x2 (12, N = 240) = 28.932, p < .05) . We also

found that there is a correlation between how Băsescu is evaluated and his

association with the deficits of the current government (ρ=.255; ρ>0,01; N=394).

Thus, the more a tabloid mentions this topic, the more this candidate receives

negative references.

As for the way in which the current president was presented in connection with

his family, no negative evaluations exist in the electoral campaign period.

However, this tendency changes when it comes with how the candidate is

illustrated in relation to his campaign events. As figure 11 shows, the negative

references outnumber the positive and neutral ones (N=126). Also, we found that

there is a significant, yet weak correlation between the way in which he is

generally evaluated and his assessments, not only in the campaign period

(ρ=.183; ρ>0,01; N=394).

Fig. 12. Types of references to

the candidate in connection with the televised debates

When designing the categories of our analysis, we considered the televised

debates a distinct moment of illustrating the candidates, which is why we did

not include them in the category of the campaigning events. Within the articles

dedicated to this subject, Băsescu received 52.6% negative evaluations, 26.3%

neutral assessments and 21.1% positive references, as illustrated below (x2(6, N

= 19) = 27.932, p < .05). From this perspective, his portrayal would

not seem to have been marked by negativism. Still, we have to consider that if

these negative references were added to those included in the campaign events

category, the resulting image would differ. In this regard, a higher number of

positive evaluations in connection to the televised debates would have provided

for an overall balanced image of Băsescu as a candidate.

As for how the tabloids presented this candidate in relation to the issue of

the alleged child agression, we found that, overall, Băsescu received mostly

positive references (81,81%, N=22). They were found mostly in Libertatea’s

coverage of the event (68,42%), followed by Cancan (26,31%) and Apropo (5,27%)

(x2(9, N = 19) = 35.429, p < .05).

Hence, the hypothesis of negativism is only partially confirmed. While overall,

Traian Băsescu was evaluated in a negative manner, this assessment varies within

each of the subcategories we subjected to this analysis and, for some topics, in

certain periods and tabloids. Thus, the tabloid with the highest number of

negative references concerning this candidate was Libertatea, followed by Apropo

and Cancan. Libertatea was also the sheet providing most of the mentions about

Băsescu

Before the electoral campaign, Băsescu, as the current president, was referred

at mostly in a negative manner, in relation to the government’ deficits and

specifically the theme of strikes, wage reduction (or the economic crisis).

Within this time range, the negative references associated to his family were

outnumbered by the positive ones.

In the electoral campaign period, the overall trend of presenting Băsescu was

preserved. Thus, he has been portrayed in a negative fashion, in connection to

the subject of the economic crisis. This tendency was also maintained in what

concerns his evaluation as a candidate: the references concerning his campaign

events are mostly negative and those relating to the televised debates are

equally negative and neutral. Although we might understand the latter as a sign

of a balanced assessment, if we were to add the mentions from this category with

those included in the campaign events category, we would obtain a rather

negative image of this candidate.

As for the way in which the current president was presented in relation to his

family, no negative evaluations exist in this period.

In connection to the issue of the alleged child aggression, we found that

Băsescu received mostly positive references. They were found mostly in

Libertatea’s coverage of the event, followed by Cancan and Apropo.

Thus, despite the fact that this candidate was mostly evaluated in a

negative fashion, due to his association with the deficits of the current

government and the negative assessments he received during the electoral

campaign, our hypothesis does not fully stand. In relation to

Băsescu’s family and his alleged aggression of a child, the tabloids have

illustrated a positive outlook over the candidate.

While it is true that our research drew the gloomiest picture of what one might

call „negativism”, it did so not only to prove the lack of consistency in some

academic accounts of tabloidization, but also to highlight the specificity of

Romanian tabloids. In the terms of our research hypothesis, it is safe to claim

that tabloids’ coverage of the last presidential campaign was somewhat marked by

negativism.

However, the reasons that lay behind this negative coverage might exceed the

boundaries of its commercial rationale. Particularly in the case of the 2009

campaign, when the Romanian society was starting to manifest its deepest

concerns about its social and political being in the context of the economic

crisis, the tendency of evaluating the current president in negative terms

is, to a certain extent, understandable. Furthermore, considering that

Băsescu‘s appraisal throughout the electoral campaign was somewhat influenced by

the different breaches of civility in the campaign itself (clashes between party

members, inter-party verbal attacks, populist campaigning strategies); its

negative tone is justifiable, to a certain extent.

6. Conclusions of the empirical analysis. Discussion

The first hypothesis of our investigation of the tabloidization

phenomenon was that if the references concerning Băsescu’s allegedly aggression

of a child outnumber those concerning his campaign events, candidature or

presidential position (deficits of the government); than the tabloids are a

subject of a high degree of sensationalism.

Because in the period when this topic appeared on the sheets’ agenda, its

proportion was lower than all of the abovementioned categories, we considered

that this hypothesis was not confirmed. Most of their

references approached Traian Băsescu’s campaign events, and not his alleged act

of violence. This trend was also confirmed in the case of each tabloid. Although

the references concerning this potential aggression outnumbered those

illustrating various deficits of the government (the economic crisis, the

cut-backs in public functionaries’ wages, union strikes, political conflicts,

accusations of corruption); we considered it a result of the long period in

which these political and social events had been highly broadcasted. Thus, since

their frequency had already diminished by the time this new controversial issue

appeared, we did not consider this finding relevant to our analysis.

Still, our empirical undertaking did not explore deeper into how the campaign

events themselves might have represented a source of sensationalism. Since they

also included references concerning different political initiatives for the

future, we considered that this category is not one to illustrate such a trait.

Further research will need to outline if what we have denominated as „campaign

events” (events happening in the course of the campaign that also include

parties’ promoting actions) is a category increasingly influenced by different

sensationalist facts.

The second assumption of our empirical research was that if the

frequency of references concerning the candidate’s family is higher than that of

the mentions regarding his image as a candidate (campaign events) or as the

president (issues of the government); then one can speak of a high degree of

personalization in the tabloid press. By exploring the candidate’s associations

with the categories specified in the methodological section of this paper, we

found that overall, this hypothesis does not confirm. The references

about Băsescu’s family amounted less than those illustrating campaign events or

deficits of the government. Thus, the tabloids have emphasized on Băsescu’s

campaign events and associations with the current government’s deficits.

Another measure of personalization that we introduced into our

analysis concerned the presence of this candidate’s pictures in most of the

articles. Since none of the tabloids seemed to have dedicated to pictures

an important part in their coverage, we considered that the personalization

hypothesis was not confirmed in this regard either. Yet, fully

validating such a hypothesis in the Romanian media landscape would require an

evolutionary approach to see whether in the past Romanian tabloids have included

fewer pictures in their articles.

Although under the terms of our framework, the hypothesis of personalization

was infirmed, this evaluation can be considered somewhat questionable from a

particular angle. If we consider the higher number of references dedicated to

Traian Băsescu’s family than that of his participation and performance in the

televised debates, then this may represent itself a sign of personalization.

Still, considering the low percentages of both of these themes and the reduced

number of articles provided by Cancan and Apropo, by comparison with Libertatea,

reaching such a conclusion would need wider samples and further investigation.

In what regards the hypothesis of negativism, this was only

partially confirmed. Despite the fact that this candidate was mostly

evaluated in a negative fashion, due to his association with the current

government’ deficits, specifically, the economic crisis, and the negative

assessments he received during the electoral campaign, our hypothesis does not

fully stand. In relation to Băsescu’s family and his alleged aggression of a

child, the tabloids have illustrated a positive outlook over the candidate. For

the time being, it is safe to claim that the tabloids’ coverage of the last

presidential campaign was somewhat marked by negativism.

While it is true that our research drew an extreme picture of the negativism

hypothesis, it did so not only to prove the lack of consistency in some academic

accounts of tabloidization, but also to highlight the specificity of Romanian

tabloids.

The reasons that lay behind this negative coverage might exceed the

boundaries of its commercial rationale. Particularly in the case of the

2009 campaign, when the Romanian society was starting to manifest its deepest

concerns about its social and political being in the context of the economic

crisis, the tendency of evaluating the current president in negative terms

is understandable. Furthermore, considering that Băsescu‘s appraisal

throughout the electoral campaign was somewhat influenced by the different

breaches of civility in the campaign itself (clashes between party members,

inter-party verbal attacks, populist campaigning strategies); its negative tone

is consistent, to a certain extent.

Hence, in the framework of our research design, we can say that the only mark

of tabloidization in the Romanian tabloid media is that of negativism. Still, as

we have shown, this trait may be considered somewhat justified by the contextual

variables that defined the 2009 presidential campaign.

Perhaps a qualitative approach of the language and style used in the Romanian

tabloids would make for a better instrument for assessing their degree of

tabloidization. While coding the data, we noticed that some of the headlines

have made use of various humorous forms (“They had some laughs in the

[televised] confrontation!”83;

„The partnership for Timişoara was signed, but the people from Timişoara have

not resigned [to it]84”).

Thus, they might represent a sign of what Fiske called „ideological resistance”85.

Nonetheless, future research in the Romanian tabloid media should explore this

assumption.

The findings of our research seem to point that there is a certain degree of

similarity between the Romanian and the Bulgarian tabloids, as illustrated in

the Media Sustainability Index86.

As shown in the course of our analyses, the three sheets have dedicated an

important place to the issues of the current government and have also mentioned

the parties’ plans for the future mandate. Thus, in the analysis of

transformations in political communication, it would be interesting to see

whether there is a specific, Eastern European type of tabloidization; that

implies an inverse polarization between what is commonly understood as the style

of tabloids and that of the so-called „quality press”.

So what are the implications of this research for the Romanian public sphere?

As we have seen, in the terms proposed by our framework, the three tabloids have

neither been affected by sensationalism or personalization. Their negative

coverage on some issues can be understood as a healthy democratic attitude

toward the troubles of the Romanian society and how they are dealt with by the

national authorities. Because usually internal issues are attributed to the

president, although his prerogatives are reduced, we considered the tabloids’

tendency to ascribe them to Băsescu as natural. Furthermore, this might also be

the result of his previous campaigning actions, which have conveyed the idea of

the omnipotent president.

For the time being, it is difficult to say whether these tabloids might have

coagulated in an alternative public sphere. An investigation of the mainstream

„quality” press would be needed in this regard and so would a further exploring

into the language and style of the tabloids.

The similarities observed between Romania and Bulgaria in what concerns the

approach of political issues in tabloids raise a number of questions: Are there

other common patterns in the East European mediated public spheres? Or is there

an Eastern European public sphere? If so, what are issues it is confronted with?

Bibliography

Adorno, Theodor, Horkheimer Max, „The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as

Mass Deception”, in Simon During (editor), The Cultural Studies Reader

, London, Routledge, 1993.

Asp, Kent, Esaiasson, Peter, „The Modernization of Swedish Campaigns:

Individualization, Professionalization, and Medialization”, in David L. Swanson,

Paolo Mancini (editors) Politics, Media, and Modern Democracy. An

International Study of Innovations in Electoral Campaigning and Their

Consequences , Westport, Connecticut, Praeger, 1996.

Aszalos, Cristian, Crampoanele României şchioape. Tabloidizarea presei

sportive româneşti (The crampons of limping Romania. The tabloidization

of the Romanian sport press) ,Cluj-Napoca, Eikon, 2011.

Barnett, Steven, „Dumbing Down or Reaching Out : Is it Tabloidisation wot done

it ?”, The Political Quarterly 69(1998).

Baum, Matthew A., „Sex, lies, and war: How soft news brings foreign policy to

the inattentive public”, American Political Science Review, 96/

1(2002).

Beciu, Camelia, Comunicare şi discurs mediatic. O lectură sociologică

(Communication and media discourse. A sociological reading) ,

Bucharest, Comunicare.ro, 2009.

Beciu, Camelia, Sociologia comunicării şi a spaţiului public (The

sociology of communication and of the public space) , Iaşi, Polirom, 2011.

Bird, S. Elizabeth, „News We Can Use : An Audience Perspective On The

Tabloidisation of News in the United States”, The Public 5/3 (1998).

Blumler, Jay, Gurevitch, Michael, The Crisis of Public Communication,

London, Routledge, 1995).

Blumler, Jay, Kavanaugh, Dennis, „The Third Age of Political Communication:

Influences and Features”, Political Communication 16 (1999).

Bourdieu, Pierre, On television, translated by Priscilla Parkhurst

Ferguson, New York, The New Press, 1996.

Brants, Kees,“Who’s Afraid of Infotainment?” European Journal of

Communication 13/ 3(1998).

Burnes, Susan, „Metaphors in press reports of elections: Obama walked on water,

but Musharraf was beaten by a knockout” , Journal of Pragmatics 43/8

(2011).

Cappella, Joseph N., Jamieson, Kathleen Hall, Spiral of Cynicism: The Press

and the Public Good , New York, Oxford University Press, 1997.

Caspi, Dan, „American-Style Electioneering in Israel: Americanization versus

Modernization”, in David L. Swanson, Paolo Mancini (editors) Politics,

Media, and Modern Democracy. An International Study of Innovations in Electoral

Campaigning and Their Consequences (Westport, Connecticut: Praeger,

Dahlgren, Peter, Television and the Public Sphere. Citizenship, Democracy

and the Media (London: Sage Publications, 1995).

De Beus, Jos, „Audience Democracy: An Emerging Pattern in Postmodern Political

Communication”, in Kees Brants, Katrin Voltmer (editors) Political

Communication in Postmodern Democracy. Challenging the Primacy of Politics

(New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011).

Delli Carpini, Michael X.; Williams, Bruce A.,“Let us infotain you: Politics in

the new media environment”, in W. Lance Bennett, Robert M. Entman (editors),

Mediated Politics. Communication in the future of democracy (New York:

Cambridge University Press, 2001).

Eisenlohr, Patrick, „Religious Media, Devotional Islam, and the Morality of

Ethnic Pluralism in Mauritius“, World Development 39/2 (2010).

Esser, Frank, „Tabloidization’ of News : A Comparative Analysis of

Anglo-American and German Press Journalism”, European Journal of

Communication 14/ 3 (1999).

Ferré-Pavia, Carme, Gayà-Morlà, Catalina, „Infotainment and citizens ’

political perception : Who’ s afraid of «Polònia»”? Catalan Journal of

Communication & Cultural Studies, 3/1(2011).

Fiske, John, Television Culture (London and New York: Routledge,

1987).

Fiske, John,“Popularity and the Politics of Information”, in Peter Dahlgren,

Collin Sparks (editors) Journalism and Popular Culture (Newbury Park:

Sage, 1992).

Franklin, Bob, „Newszak: entertainment versus news and information”, in Anita

Biressi & Heather Nunn (editors) The Tabloid Culture Reader (New York:

McGraw Hill Open University Press, 2008).

Franklin, Bob, Newszak and Newsmedia. (London: Arnold, 1997).

Gitlin, Todd,“Bites and blips : chunk news , savvy talk and the bifurcation of

American politics”, in Peter Dahlgren, Collin Sparks (editors),

Communication and Citizenship: Journalism and the Public Sphere in the New Media

Age , London, Routledge, 1991.

Głowacki, Michał, Dobek-Ostrowska, Bogusława, Comparing Media Systems in

Central Europe (Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu

Wrocławskiego, 2008).

Glynn, Kevin, „Tabloid Television’s Transgressive Aesthetic: A Current Affair

and the «Shows that Taste Forgot»”, Wide Angle 12/2 (1990).

Habermas, Jürgen, The structural transformation of the public sphere. An

inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society , translated by Thomas Burger

in collaboration with Frederick Lawrence (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1962/ 1989), 27.

Hallin, Daniel C., „Sound bite news: Television coverage of elections,

1968–1988”, Journal of Communication, 42/ 2 (1992).

Hart, Roderick P., Seducing America: How Television Charms the Modern Voter,

New York, Oxford University Press, 1994.

Hartley, John, Green, Joshua, „The public sphere on the beach”, European

Journal of Cultural Studies, 9/3 (2006).

Himmelstrand, Ulf, „A Theoretical and Empirical Approach to Depoliticization

and Political Involvement”, Acta Sociologica. Approaches to the Study of

Political Participation, 6(1962).

Holly, Werner, „Tabloidisation of political communication in the public

sphere”, in Ruth Wodak,Veronika Koller, (editors) Handbook of Communication

in the Public Sphere (Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2008).

Holtz-Bacha, Christina, „Professionalization of Political Communication”,

Journal of Political Marketing 1/4 (2002).

Jakubowicz, Karol, „Television and Elections in Post-1989 Poland: How Powerful

Is the Medium?”, in David L. Swanson, Paolo Mancini (editors) Politics,

Media, and Modern Democracy. An International Study of Innovations in Electoral

Campaigning and Their Consequences (Westport, Connecticut: Praeger,

Jamieson, Kathleen Hall, Birdsell, David S., Presidential debates. The

challenge of creating an informed electorate , New York, Oxford University

Press, 1988.

Johansson, Sofia, „«They Just Make Sense»: Tabloid Newspapers as an Alternative

Public Sphere”, in Richard Butsch, (editor) Media and Public Spheres,

New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

Jones, Jeffrey P., Entertaining politics: new political television and

popular culture, Maryland , Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2005).

Klein, Ulrike,“Tablodised political coverage in Bild-Zeitung”, The Public

5/3 (1998).

Langer, John, Tabloid television: popular journalism and the ‘other news’

, London & New York, Routledge, 1998.

Lee, Chin-Chuan, Chinese Media,Global Contexts , London, Routledge,

2003.

Livingstone, Sonia, Lunt, Peter, Talk on television. Audience Participation

and Public Debate ,New York, Routledge, 1994/2001.

Lunt, Peter, Pantti, Mervi, „Popular Culture and the Public Sphere: Currents of

Feeling and Social Control in Talk Shows and Reality TV”, in Richard Butsch

(editor) Media and Public Spheres New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

Manning, Paul, News and News Sources: A Critical Introduction, London,

Sage, 2001.

Mazzoleni, Gianpietro, Schulz, Winfried, „«Mediatization» of Politics: A

Challenge for Democracy”? Political Communication 16/ 3 (1999).

McGuigan, Jim, „The Cultural Public Sphere”, European Journal of Cultural

Studies 8/4 (2005).

McKee, Allan, The Public Sphere: An Introduction (New York: Cambridge

University Press, 2005)

McNair, Brian, Journalism and Democracy: An Evaluation of the Political

Public Sphere , London, Routledge, 2000.

Mehl, Dominique, „The television of intimacy. Meeting a social need”,

Réseaux. The French journal of communication 4/ 1(1996).

Negrine, Ralph, Papathanassopoulos, Stylianos, „The «Americanization» of

Political Communication: A Critique”, The International Journal of Press/

Politics, 1/2 (1996).

Nörnebring, Henrik, Jönsson, Anna Maria, „Tabloid Journalism and the Public

Sphere: a historical perspective on tabloid journalism”, Journalism Studies

5/3 (2004).

Postman, Neil, Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of

Showbusiness , New York, Penguin, 1986.

Putnam, Robert, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American

Community , New York, Simon & Schuster, 1995.

Roberts, John Michael, „Introducing Competence and the Public Sphere”, in

The Competent Public Sphere , New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

Robinson, Michael J.,“Public affairs television and the growth of political

malaise: The case of «The selling of the pentagon»”, The American Political

Science Review, 70/2 (1976).

Rooney, Dick, „Dynamics of the British tabloid press”, The Public 5/3

(1998).

Scammel, Margaret,“The wisdom of the war room: US campaigning and

Americanization”, Media, Culture and Society, 20 (1998).

Schiff, Frederick, „The Dominant Ideology and Brazilian Tabloids: News Content

in Class-Targeted Newspapers”, Sociological Perspectives 39/1 (1996).

Sparks, Collin, „Popular Journalism: Theories and Practice”, in Peter Dahlgren,

Collin Sparks (editors) Journalism and Popular Culture, London, Sage,

1992.

Sparks, Collin, Tulloch, John, Tabloid tales: Global debates over media

standards, Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2000.

Stamper, Judith, Brants, Kees, „A Changing Culture of Political Television

Journalism”, in Kees Brants, Katrin Voltmer (editors) Political

Communication in Postmodern Democracy. Challenging the Primacy of Politics

, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Street, John, „The Transformation of Political Modernity?”, in Barrie Axford,

Richard Huggins (editors) New Media and Politics , London, Sage

Publications, 2001.

Street, John, „«Prime time politics»: Popular culture and politicians in the

UK”, The Public 7/2 (2000).

Street, John, Inthorn, Sanna, Scott, Martin, „Playing at Politics? Popular

Culture as Political Engagement”, Parliamentary Affairs 65 (2012).

Strömbäck, Jesper, „Four Phases of Mediatization: An Analysis of the

Mediatization of Politics”, International Journal of Press/Politics

13/3 (2008).

Swanson, David L., Mancini, Paolo (editors) Politics, Media, and Modern

Democracy. An International Study of Innovations in Electoral Campaigning and

Their Consequences, Westport, Connecticut, Praeger, 1996.

Temple, Mick,“Dumbing Down is Good for You”, British Politics 1(2006)

NOTE

1

Beneficiary of the „Doctoral Scholarships for a Sustainable

Society” project, co-financed by the European Union through the European

Social Fund, Sectoral Operational Programme Human Resources and

Development, 2007-2013.

2 Jürgen Habermas, The structural

transformation of the public sphere. An inquiry into a Category of

Bourgeois Society , translated by Thomas Burger in collaboration with

Frederick Lawrence (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1962/ 1989), 27.

3 A specific line of theorization in the

established literature has analyzed how the initial Habermasian definition

can generate new paradigms of the public sphere. We consider the following

works as being illustrative for this type of theoretical research: Patrick

Eisenlohr, „Religious Media, Devotional Islam, and the Morality of Ethnic

Pluralism in Mauritius“, World Development 39/2 (2010); Jim

McGuigan, „The Cultural Public Sphere”, European Journal of Cultural

Studies 8/4 (2005); Allan McKee, The Public Sphere: An

Introduction (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005); John

Michael Roberts, „Introducing Competence and the Public Sphere”, in The

Competent Public Sphere (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009).

4 For instance the stand promoted by:

Roderick P. Hart, Seducing America: How Television Charms the Modern

Voter (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994); Kathleen Hall

Jamieson, David S. Birdsell, Presidential debates. The challenge of

creating an informed electorate (New York: Oxford University Press,

1988).

5 Ralph Negrine, Stylianos

Papathanassopoulos, „The «Americanization» of Political Communication: A

Critique”, The International Journal of Press/Politics, 1/2

(1996); Margaret Scammel, „The wisdom of the war room: US campaigning and

Americanization”, Media, Culture and Society, 20 (1998).

6 Jos De Beus, „Audience Democracy: An

Emerging Pattern in Postmodern Political Communication”, in Kees Brants,

Katrin Voltmer (editors) Political Communication in Postmodern

Democracy. Challenging the Primacy of Politics (New York: Palgrave

Macmillan, 2011).

7 The alleged tabloidization of

political communication has been both postulated and explored in studies

such as: S. Elizabeth Bird, „News We Can Use : An Audience Perspective On

The Tabloidisation of News in the United States”, The Public 5/3

(1998); Frank Esser, „Tabloidization’ of News : A Comparative Analysis of

Anglo-American and German Press Journalism”, European Journal of

Communication 14/ 3 (1999); Bob Franklin, Newszak and Newsmedia.

(London: Arnold, 1997); Bob Franklin, „Newszak: entertainment versus news

and information”, in Anita Biressi & Heather Nunn (editors) The Tabloid

Culture Reader (New York: McGraw Hill Open University Press, 2008);

Ulrike Klein, „Tablodised political coverage in Bild-Zeitung”, The

Public 5/3 (1998); Dick Rooney, „Dynamics of the British tabloid

press”, The Public 5/3 (1998); Raymond Williams,

Communications (Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin, 1962).

8 Franklin, Newszak, 1997;

Joseph N.Cappella, Kathleen Hall Jamieson, Spiral of Cynicism: The

Press and the Public Good (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

9 Franklin, Newszak, 1997; Paul

Manning, News and News Sources: A Critical Introduction (London:

Sage, 2001); Brian McNair, Journalism and Democracy: An Evaluation of

the Political Public Sphere (London: Routledge, 2003); Mick Temple,

„Dumbing Down is Good for You”. British Politics 1(2006)

10 In this regard Rooney, „Dynamics”,

1998 represents an illustrative example of such a positioning.

11 Bird, „News”, 1998.; Pierre

Bourdieu, On television, translated by Priscilla Parkhurst

Ferguson (New York: The New Press, 1996); Franklin, Newszak,

1997; John Langer, Tabloid television: popular journalism and the

‘other news’ (London & New York: Routledge, 1998); Rooney, „Dynamics”,

1998.

12 Habermas, „Structural”, 1962/ 1989.

13 Habermas, „Structural”, 1962/ 1989.

14 Jay G. Blumler, Dennis Kavanaugh,

„The Third Age of Political Communication: Influences and Features”,

Political Communication 16 (1999); Jesper Strömbäck, „Four Phases

of Mediatization: An Analysis of the Mediatization of Politics”,

International Journal of Press/Politics 13/3 (2008); Judith Stamper,

Kees Brants, „A Changing Culture of Political Television Journalism”, in

Kees Brants, Katrin Voltmer (editors) Political Communication in

Postmodern Democracy. Challenging the Primacy of Politics (New York:

Palgrave Macmillan, 2011).

15 Gianpietro Mazzoleni, Winfried

Schulz, „«Mediatization» of Politics: A Challenge for Democracy”?

Political Communication 16/ 3 (1999).

16 Peter Dahlgren, Television and

the Public Sphere. Citizenship, Democracy and the Media (London: Sage

Publications, 1995).

17 Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer,

„The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception”, in Simon During

(editor), The Cultural Studies Reader (London: Routledge, 1993);

Jay Blumler, Michael Gurevitch, The Crisis of Public Communication

(London: Routledge, 1995); Todd Gitlin, „Bites and blips : chunk news ,

savvy talk and the bifurcation of American politics”, in Peter Dahlgren,

Collin Sparks (editors), Communication and Citizenship: Journalism and

the Public Sphere in the New Media Age (London: Routledge, 1991);

Hart, Seducing, 1994; Jamieson, Birdsell, Presidential

debates, 1988; Dominique Mehl, „The television of intimacy. Meeting a

social need”, Réseaux. The French journal of communication 4/

1(1996); Neil Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in

the Age of Showbusiness (New York: Penguin, 1986).

18 Robert Putnam, Bowling Alone:

The Collapse and Revival of American Community (New York: Simon &

Schuster, 1995).

19 Bourdieu, On television,

1996 ; Capella, Jamieson, Spiral, 1997.

20 Franklin, Newszak, 1997;

Franklin , „Newszak”, 2008.

21 Adorno, Horkheimer, „The Culture”,

1993.

22 Mehl, „The television”, 1996.

23 Michael X. Delli Carpini, Bruce

A.Williams, „Let us infotain you: Politics in the new media environment”,

in W. Lance Bennett, Robert M. Entman (editors), Mediated Politics.

Communication in the future of democracy (New York: Cambridge

University Press, 2001).

24 Rosa Van Santen, Popularization

& Personalization. A Historical and Cultural Analysis of 50 Years of Dutch

Political Television Journalism (Amsterdam, the Netherlands:

Almanakker, Oosterhout, 2012).

25 Kees Brants, „Who’s Afraid of

Infotainment?” European Journal of Communication 13/ 3(1998); John

Street, „«Prime time politics»: Popular culture and politicians in the UK”,

The Public 7/2 (2000).

26 Camelia Beciu, Comunicare şi

discurs mediatic. O lectură sociologică ( Communication and media

discourse. A sociological reading) (Bucharest: Comunicare.ro, 2009);

Camelia Beciu, Sociologia comunicării şi a spaţiului public ( The

sociology of communication and of the public space) (Iaşi: Polirom,

2011); Blumler, Kavanaugh, „The Third”, 1999.; Ulf Himmelstrand, „A

Theoretical and Empirical Approach to Depoliticization and Political

Involvement”, Acta Sociologica. Approaches to the Study of Political

Participation, 6(1962); Christina Holtz-Bacha, „Professionalization of

Political Communication”, Journal of Political Marketing 1/4

(2002); David L. Swanson, Paolo Mancini (editors) Politics, Media, and

Modern Democracy. An International Study of Innovations in Electoral

Campaigning and Their Consequences (Westport, Connecticut: Praeger,

1996).

27 McNair, Journalism,2000;

Postman, Amusing, 1986; Temple, „Dumbing”, 2006.

28 Gitlin, „Bites”, 1991; Daniel C.

Hallin, „Sound bite news: Television coverage of elections, 1968–1988”,

Journal of Communication, 42/ 2 (1992); Hart, Seducing, 1994;

Michael J. Robinson, „Public affairs television and the growth of political

malaise: The case of «The selling of the pentagon»”, The American

Political Science Review, 70/2 (1976).

29 Gitlin, „Bites”, 1991.

30 Blumler & Kavanaugh, 1999;

Himmelstrand, „A Theoretical,” 1962; Holtz-Bacha, „Professionalization”,

2002; Swanson, Mancini, Politics, 1996; Van Santen,

Popularization, 2012.

31 Beciu, Comunicare, 2009;

Beciu, Sociologia, 2011; Blumler, Kavanaugh, „The Third”, 1999;

Holtz-Bacha, „Professionalization”, 2002; Swanson, Mancini, Politics,

1996.

32 De Beus, „Audience” : 19.

33 Capella, Jamieson, Spiral,

1997.

35 Brants, „Who’s Afraid”, 1998;

Dahlgren, Television,1995; Jeffrey P. Jones, Entertaining

politics: new political television and popular culture (Maryland:

Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2005).

36 Brants, „Who’s Afraid”, 1998.

36 e.g. Dan Caspi, „American-Style

Electioneering in Israel: Americanization versus Modernization”, in David

L. Swanson, Paolo Mancini (editors) Politics, Media, and Modern

Democracy. An International Study of Innovations in Electoral Campaigning

and Their Consequences (Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 1996); Kent

Asp, Peter Esaiasson, „The Modernization of Swedish Campaigns:

Individualization, Professionalization, and Medialization”, in David L.

Swanson, Paolo Mancini (editors) Politics, Media, and Modern Democracy.

An International Study of Innovations in Electoral Campaigning and Their

Consequences (Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 1996).

37 Delli Carpini,Williams, „Let us

infotain”, 2001; Jones, Entertaining, 2005; Sonia Livingstone,

Peter Lunt, Talk on television. Audience Participation and Public

Debate (New York: Routledge, 1994/2001); McNair, Journalism,2003;

Street, „«Prime time politics»”, 2000; John Street, „The Transformation of

Political Modernity?”, in Barrie Axford, Richard Huggins (editors) New

Media and Politics (London: Sage Publications, 2001); Temple,

„Dumbing”, 2006; Liesbet Van Zoonen, Stephen Coleman, Anke Kuik, „The

Elephant Trap: Politicians Performing in Television Comedy”, in Kees

Brants, Katrin Voltmer (editors) Political Communication in Postmodern

Democracy. Challenging the Primacy of Politics (New York: Palgrave

Macmillan, 2011).

38 Matthew A. Baum, „Sex, lies, and

war: How soft news brings foreign policy to the inattentive public”,

American Political Science Review, 96/ 1(2002); Van Zoonen, Coleman,

Kuik, „The Elephant”, 2011; Temple, „Dumbing”, 2006.

39 Carme Ferré-Pavia, Catalina

Gayà-Morlà, „Infotainment and citizens ’ political perception : Who’ s

afraid of «Polònia»”? Catalan Journal of Communication & Cultural

Studies, 3/1(2011).

40 Jones, Entertaining, 2005;

Livingstone, Lunt, Talk, 1994/2001.

41 John Street, Sanna Inthorn, Martin

Scott, „Playing at Politics? Popular Culture as Political Engagement”,

Parliamentary Affairs 65(2012); Liesbet Van Zoonen, Entertaining

the citizen: When politics and popular culture converge (Oxford, UK:

Rowman & Littlefield, 2005).

42 Ferré-Pavia, Gayà-Morlà,

„Infotainment”, 2011.

43 Peter Lunt, Mervi Pantti, „Popular

Culture and the Public Sphere: Currents of Feeling and Social Control in

Talk Shows and Reality TV”, in Richard Butsch (editor) Media and Public

Spheres (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005); David Nolan,

„Tabloidisation Revisited” (1998),

http://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=427191853059782;res=IELHSS

1998, retrieved 03.08. 2012.

44 John Fiske, Television Culture

(London and New York: Routledge,1987).

45 John Hartley, Joshua Green, „The

public sphere on the beach”, European Journal of Cultural Studies

9/3 (2006); McKee, The Public Sphere, 2005.

46 McGuigan, „The Cultural”, 2005,

435.

47 Van Zoonen, Coleman, Kuik, „The

Elephant”, 2011.

48 Collin Sparks, „Popular Journalism:

Theories and Practice”, in Peter Dahlgren, Collin Sparks (editors)

Journalism and Popular Culture (London: Sage, 1992).

49 Blumler, Kavanaugh, „The Third”,

1999; Gitlin, „Bites”, 1991; Henrik örnebring, Anna Maria Jönsson, „Tabloid

Journalism and the Public Sphere: a historical perspective on tabloid

journalism”, Journalism Studies 5/3 (2004).

50 Susan Burnes, „Metaphors in press

reports of elections: Obama walked on water, but Musharraf was beaten by a

knockout” , Journal of Pragmatics 43/8 (2011); Werner Holly,

„Tabloidisation of political communication in the public sphere”, in Ruth

Wodak,Veronika Koller, (editors) Handbook of Communication in the

Public Sphere (Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2008).

51 Van Santen, Popularization,

2012.

52 Burnes, „Metaphors”, 2011;

Franklin, Newszak, 1997; Franklin , „Newszak”, 2008; Lian Zhu,

„Tabloidisation with Chinese characertistics: a case study of Depth 105”,

Critical Arts 25/1 (2011).

53 Steven Barnett, „Dumbing Down or

Reaching Out : Is it Tabloidisation wot done it ?”, The Political

Quarterly 69(1998); Bird, „News”, 1998; Blumler, Kavanaugh, „The

Third”, 1999; Connell, 1998; Franklin, Newszak, 1997; Franklin ,

„Newszak”, 2008; Collin Sparks, John Tulloch, Tabloid tales: Global

debates over media standards ( Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield,

2000).