|

Discriminări

Using nonverbal

sensitivity and cognitive style

to discriminate between self and others’ prosocial

behavior1

LOREDANA IVAN

[The University of

Bucharest]

Abstract:

Using dictator game, we evaluated participants

(N = 80 students) social value orientations and

found that prosocial orientation was shared by the

majority of the participants. The current research

provides also evidence for the holier than thou

effect: participants tended to underestimate fellow

participants’ altruism relative to their own

behavior. We underlined the fact that the fairness

bias is larger for participants having an

individualistic approach and for the estimations of

unknown stimuli behavior, in brief exposure

situations. We used type of information processing

and nonverbal sensitivity to explain participants’

accuracy in estimating stimuli persons’ behavior.

The data suggest that subjects who tended to use

more their cognitive abilities were significant more

accurate in predicting stimuli persons’ social value

orientations and they had also higher abilities to

decode nonverbal cues.

Keywords:

social value orientation; dictator game;

nonverbal sensitivity; Rational-Experiential

Inventory (REI); ways to process information

Introduction

Every day interactions rise questions about others’ sincerity and morality. For example, we are wondering if the food we purchase in the market is indeed chemical-free as the vender claims or whether our co-workers are altruistic enough to share with us information about a new job opportunity. Most of the times, when people are in interdependency situations with others they briefly know about, questions about their morality arise. In the current work, we use the term „interdependency” referring to situations in which two ore more social actors are interacting with each other so that the outcome of one’s actions is dependent of the outcome of the other one’s actions A football game is one typical interdependency situation, in which one single player could not influence the score, unless the other players are coordinating also their actions with him.

Van Lange and collaborators2 indicated that social value orientation is a relative stable personality trait and it predicts people’s helping behavior in interdependency situations. From this point of view, Van Lange distinguished between individualists, prosocials, and competitors, as three types of social value orientations. Prosocials are described as social actors who look to maximize benefits for all involved in the situation, and to diminish the differences; Individualists are depicted as social actors who tend to get as much as possible from the situation, without taking into account others’ benefits; Competitors are social actors who use others as anchors, in order to evaluate their own costs and benefits: They try to maximize benefits relative to others involved in the situation. Prosocials seem to follow a collective rationality, expecting others also to cooperate and, as a result, they are more interested in information about people’s honesty. Prosocials tend to interpret situations in terms of morality principles: „all for one and one for all”, while individualists and competitors are more interested in the competence and the intelligence of their interaction partners’ using „let the best win” as a ruling principle.

Van Lange and collaborators3 have estimated that the prosocial value orientation is shared by a larger segment of population, compare to the individualist and the competitive ones. Moreover, several studies4 have proved that people tend to underestimate others’ prosocial behavior5 and perceive themselves as being more honest and altruistic than others6. Although prosocial value orientation seems to be more spread than the individualistic one, people systematically underestimate others’ prosociality7 .

The underestimation of others’ morality relative to self is well-known in the literature as „the holier than thou effect”8 or „fairness bias”9. Such an error is mainly non-adaptive because it could determine people to avoid choosing others as interaction partners and they may loose the benefits of working together. The holier than thou effect is accentuated in the case of those having individualist social value orientation compare to those having prosocial value orientation, due to the self-projection phenomenon: Individualists will tend to estimate that others will share their views of maximizing benefits regardless relational consequences, and this will increase the general effect of underestimating others’ morality10.

The current research investigates whether people are able to make accurate predictions on real others’ prosociality – using Van Lange distinction between prosocials, individualists, and competitors – in a briefly exposure situation. We predict that participants having an individualist social value orientation will tend to underestimate also others’ prosociality, when using real stimuli persons; the effect will be stronger when we compare to participants having a prosocial value orientation (H1). Previous research on fairness bias have asked people to compare themselves with „general others” or „abstract others” (i.e „student from your class”; „people having the same age with you”). For example, in a study conducted by Van Lange and Sedikides11, participants – students from Free University of Amsterdam – have been asked to compare themselves with the mean students from the same university – and we do not know whether the same holier than thou effect takes place when participants compare themselves with real stimuli persons. In short, the current study predicts that the holier than thou effect is larger when people compare themselves with unknown but real stimulus persons, in a real interdependency situation. We argue that, by asking people to compare themselves with „real others”, we increase the pressure to interpret situation in morality terms and this will result in a higher fairness bias.

Research about decoding others’ psycho-social characteristics based on brief exposure situations12 proved that individuals are surprisingly accurate13. A meta-analysis of the studies that have tested first impressions’ accuracy14 has indicated that people were able to decode subtle nonverbal cues and to make correct estimations about others’ personality traits, performances in different areas of activity (e.g. job interviews), values and sexual orientation, also about the quality of interpersonal relations15. However, no similar research has been conducted on the first impressions’ accuracy when estimating others’ prosociality or social value orientation.

This research line, which claims that our first impression could be surprinsingly accurate, followed by Ambady and collaborators, uses ecological arguments to explain why some groups are more able to estimate particular traits: the accuracy in decoding a particular aspect is very much depended on the adaptive value of that trait for the group we refer to. Thus, for example reading teachers’ non-discriminatory behavior in class is more important for students than for adults16 and the results of the of some experimental studies17 showed that indeed students had more accurate first impressions regarding the behavior of several unknown teachers, than adults. The ecologic explanation could be a strong argument in the case of social value orientation too. Why do we think that people might be accurate in reading others’ prosociality when they are briefly exposed to stimuli persons? Ontogenetically speaking, it could be useful for an individual to decode properly the social value orientation of an interaction partner from the first beginning, because this could save him/her a lot of trouble or costs associated with perceiving trustworthy somebody who is not.

Additionally, people might be more or less sensitive to nonverbal cues in general. Participants’ general ability to decode nonverbal behavior could influence their accuracy in estimating others’ social value orientation, especially in case of brief exposure situations. The concept of nonverbal sensitivity18refers to individual differences in perceiving, decoding and interpreting social situations19 and claims that such ability influence the way we interact with others20 and make sense of the social information in general21. We hypothesize that participants having high accuracy in decoding nonverbal cues in general, will have also more accurate first impressions, when they will be asked to estimate real others’ prosociality, in a brief exposure situation (H2). Thus, we predict a positive correlation between participants’ general nonverbal sensitivity and their ability to reach accurate first impressions on stimuli persons in a particular situation.

Studies about first impressions’ accuracy found that people mostly relay on intuition22. Moreover, some researchers23 argue that cognitive complex groups have modest score compare to cognitive simple groups because the former are using analytical paths to decode nonverbal cues, while the later use more „guts feelings”. The functional role of intuition24 has been revealed in the modern approaches on social cognition25. For example, Cacciopo and Petty26 have indicated that need for cognition is a relatively stable personality trait and they have also distinguished between: (1) „cognitive miseries” – those having a lower need for cognition, who relay mostly on schemas27 and prototypes, and (2) individuals who invest more in information processing, having higher need for cognition. Starting with this distinction, Pacini and Epstein28 have developed the self-model based on cognition versus intuition (CEST) claiming for two parallel and interactive systems in information processing: one rational, conscient, intended, mainly verbal, without affectivity involved and another one – experiential, pre-conscient, holistic, mainly nonverbal and affective. For the current research, we predict that participants’ need for cognition, and the way they tend to process information in general – analytic or intuitive – will influence their first impressions’ accuracy, when they will be asked to estimate unknown stimuli persons’ prosociality (H3).

In sum, the present study we assesses participants’ fairness bias when they are asked to estimate real others, in a brief exposure situation. We suggest that participants will tend to underestimate others’ prosociality even more when they are confronted to real stimuli than to „general others”. Additionally, people will use their own behavior as anchor: those having themselves an individualistic social value orientation will tend to underestimate more others’ prosociality, compare to those having themselves a prosocial value orientation. Moreover, participants’ accuracy in what regards stimuli persons’ prosociality (first impressions) will be moderated by their nonverbal sensitivity and their preference for a particular information procession style: experiential versus analytic.

Method

Participants

A total of 90 undergraduate students (76 women and 14 men), aged 18 to 22 (M = 22.4, SD = 2.40) were recruited at the Faculty of Sociology and Social Work University of Bucharest. They were told that this is a study about how accurate are our first impressions.

Stimuli

A tape with 56 stimuli persons has been previously produced to the current research. These particular subjects have been filmed when they were taking about themselves for five minutes, in front of the camera. Then we extracted 25 seconds, for each stimulus person, starting with the first moment the camera was on and they begin to talk. We let out the first five seconds, from technically reasons. The final master tape contains extracts from the 56 filmed subjects, randomly distributed, with a five seconds pause between each subject and the one. A similar tape, but with stimulus persons presented in reverse order was created to control for the stimulus persons’ exposed order.

Individual Measures

Nonverbal sensitivity. A face and body form of the Profile of Nonverbal Sensitivity test (PONS)29 has been used to assess participants’ general ability to decode subtle nonverbal cues. This form contains visual items from the full PONS, 20 body-only items and 20 face-only items, and consists in 40 slides, 2 seconds each, enacted by a young woman (aged 24, white, resident in US) who is filmed when expressing spontaneous emotions associated to different situations: some with low emotional intensity (e.g. ordering food in a restaurant), and other with high emotional intensity (e.g. expressing jealous anger). Participants have to choose the correct answer from a dual answering sheet. The face and body PONS measures nonverbal sensitivity on visual channel only, having a .63 overall reliability. The internal consistency of the PONS ranges from .86 to .92 and its median test–retest reliability is .69. The visual channel scores significantly correlate with the full PONS ( r = .50, p < .001)30.

Type of information processing. In order to assess participants’ preference to treat information analytical or intuitive, we used a Romanian version of the Rational-Experiential Inventory31 (REI). This version of REI32 has 24 items distributed on two subscales: 10 items on rational processing scale (e.g. „I am much better at figuring things out logically than most people”) and 14 items on experiential processing scale (e.g. „I like to rely on my intuitive impressions”). Participants have to answer each item using a 5 point Likert scale, from 1 (not at all true for me) to 5 (extremely true for me). The original version of REI, contained 40 items distributed on two parallel components, with analytical and rational processing style low correlated with each other (r = – .07, r = – .08, p > .05). However, the adapted version for the Romanian student population, REI 24 did not support the idea of rational and experiential processing modes as parallel systems. The two subscales – analytic and experiential – proved to be interdependent measures of the thinking style preferences (r = .422, p < .001), with high internal consistency (rational α = .88, experiential α = .93). The positive relation between the two components of REI 24 shows that the instrument rather measures a broader concept: individuals’ tendency to use their cognitive resources in general.

Social value orientations. We used a social dilemma situation – dictator game – to measure participants’ tendency to have an individualisic or prosocial value orientation33. We described a situation in which two persons (Person A and Person B) are interdependent and the situation is controlled by Person A. The situation is ruled in totally anonymous conditions; the two persons not come to know each other in the future34. The following description was given to the participants:

In this situation there are two persons (Person A and Person B). Both persons will never come to know each other before, during, or after they made their decisions. Thus, they interact with each other through an experimenter.

Person A gets 30 lei from the experimenter and she can divide the money with Person B as she wants to. The money will be divided as Person A decided.

Supposing you are in the position of Person A, what would you do with the 30 lei received from the experimenter?

I keep the 30 lei, and give 0 lei to Person B

I keep 25 lei and give 5 lei to Person B

I keep 15 lei and give 15 lei to Person B

|

Subjects had to register their choices in the position of Person A and to estimate (in percentage) what have done the fellow participants in the experiment. We considered that keeping the entire amount of money (30 lei) would indicate an individualistic value orientation, while keeping 25 lei or 20 lei would indicate a competitive approach. Also, we estimate that participants who chose to divide money equally are prosocial oriented.

Procedure

Participants were informed that they are going to take part in a study about first impressions formation and they completed the study in groups of approximately 15 students. First, they have been asked to fill the sentences of REI 24, then to answer the items from the nonverbal sensitivity test (Face and Body PONS). In the second part of the study, we presented the dictator situation and we asked them to make their choices and to estimate the choices of their fellow participants. We asked them also to estimate what the mean students from their university will do in such situation.

In the third part of the study, participants were exposed to the stimulus persons, using the master tape described before, with no sound. In a previous experimental section all 56 stimulus persons have made their choices playing dictator game so that we could measure their social value orientation. After seeing each stimulus person for 20 seconds, we stopped the tape and participants had 10 seconds to make their estimations about the real behavior of that person they did not know before. In the end we asked questions about their motivation and focused during the experiment and also we requested them to estimate how many of the stimulus persons they have correctly evaluated.

Results

Subjects behavior in the dictator game and how they estimated others’ behavior

The majority of the participants (63%) chose to divide money equally with Person B. They have chosen to share the money with a person, in an interdependency situation, without knowing that particular person and without any possibility to meeting each other in the future. Thus we found that 63% of our participants had a prosocial value orientation. These findings are consistent with the ones from the previous studies using dictator game35. Several studies have proved that the prosocial value orientation is the dominant one36, followed by the competitive and the individualistic value orientations.37 Although we had few men participants, we obtained significant gender differences, with women students showing more prosocial value orientation than men students, χ2 = 10.44, df =1, p = .01.

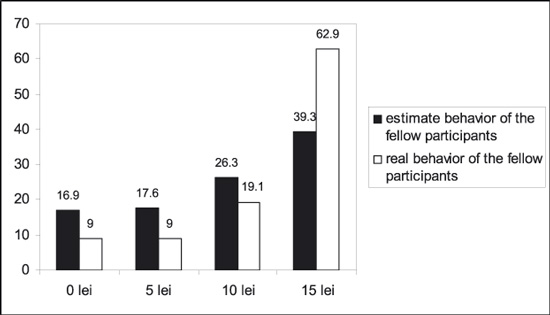

When students had to estimate others’ behavior in the dictator game, they have underestimated fellow participants’ prosocial orientation, consistent to the holier than thou effect: The mean estimated percentage of fellow students who will share the money with Person B was 39.3%, significant lower compare to the percentage who actually divided the money equally (63%). Figure 1 displays how participants think about themselves as being prosocials, while estimating others to be competitors or individualists. In other words, participants developed a type of heuristic that could be described as: „I would have divided money equally with Person B, but the others would have not. In the better case, the others would have given some money to Person B, but they would have not shared the money with that person.”

We found support for H1: the holier than thou effect was larger for participants who took themselves an individualistic approach, compare to those who tended to have an altruistic approach in the interdependency situation. There was a negative correlation between participants’ own behavior and their estimations of fellow students’ behavior, in the case of those who had and individualistic social value orientation, r(89) = - .522, p < .001 and a positive correlation between participants’ own behavior and their estimations of the fellow students’ behavior, in he case of those who had a prosocial value orientation, r(89) = .39, p < .001. These results prove that participants have used self-projection to estimate others behavior in general. The Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) shows that the fairness bias was indeed lager for participants with an individualistic social value orientation, as we have predicted, F (3, 85) = 11.466, p < .001. Post-hoc tests also show that the differences at the estimation of fellow students’ behavior are higher, when we compare to those who themselves gave „0 lei” to person B with the group who themselves gave „15 lei to Person B”.

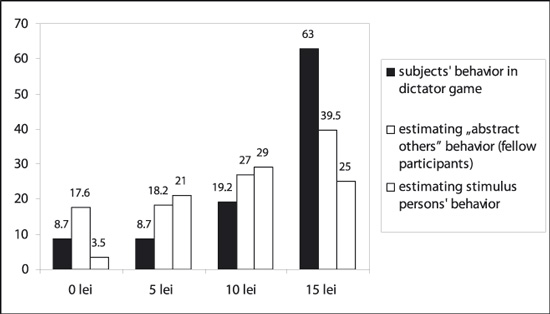

Additionally, in order to test H1, we compare stimuli persons’ real behavior in the dictator game with participants’ estimations of the same behavior. The results show that the holier than thou effect was larger, when participants had to judge unknown others they were briefly exposed to, compare to the situation when they were asked to judge fellow students, in general (Figure 2). In other words, participants were even more skeptical in judging others’ prosocial behavior, in the case of real stimuli persons whom they did not know before.

People tend to see themselves as being more prosocial oriented than the stimuli persons, but they see these unknown persons as not necessary more egoistic than themselves. Most probably they followed a similar heuristic as the one used when they had evaluated abstract others: „I would share the money equally, but this particular person will not do it. He/she would not give more than 10 lei to Person B”. Figure 2 displays that participants were more prudent in attributed egoistic behavior to stimuli persons. Brief exposure to others significantly decreases the percentage of those to whom students attributed egoistic behaviors (give 0 lei to Person B).

Nonverbal sensitivity, type of information processing, and participants’ accuracy at estimating stimuli behavior

We tested the relationship between participants’ general ability to decode nonverbal cues and their performance in estimation the social value orientation of the stimuli persons. Surprisingly, the results show a negative correlation, r (89) = -.21, p = .04, pointing in a different direction that we have predicted (H2). However, these results are due to interaction effect between Face and Body PONS scores and participants’ scores on REI, r(89) = - .28, p < .01. Participants who relayed less on intuition, and, generally speaking had a preference to use more cognitive resources, also had higher nonverbal sensitivity scores. Moreover, participants preferences to use their cognitive resources when processing information in a particular situation was a significant predictor of their accuracy in estimating stimuli behavior in the dictator game, β = .26, F(1, 89) = 2.56, p = .01. Thus, we find support for H3: participants’ preference to use cognitive resources has influenced their accuracy in estimating stimulus persons’ behavior.

Discussion

We found that majority of the participants had a prosocial value orientation and declared they would share the money equal with an unknown person, even when they were told they would not meet that person in the future. They acted altruistic although there was not in their best interest, probably because they will feldt bad otherwise. These results are consistent with previous studies that have used dictator game, which showed also that the prosocials are the larger category, followed by the competitors and the individualists. Moreover, such effect could be stronger in other interdependency situations, because the one considered in the current study (dictator game) was totally controlled by one actor. Person A has no rational reasons to share the money with Person B except for the situation when she feels committed to do so.

We also found support for holier than thou effect: participants perceived themselves as being more prosocial compare to their fellow participants in the experiment. Moreover, when participants had to estimate real others’ behavior in the dictator game, the fairness bias was larger. Seeing others that we do not know could generate more skepticisms compare to the situation when we have to evaluate abstract, but familiar others (i.e. fellow students from the same university). When exposing people to real unknown stimuli, we obtain an increased skepticism towards their possible altruistic behavior but also a decreased tendency to consider them egoistic. We may call this „nicer than thou effect” by claiming that in the interdependency situations, in which people are using their first impressions, they tend to develop some heuristics to help them estimate others’ prosociality: „this person is not necessary egoistic, but he/she is definitively not as altruistic as me”.

We hypothesized that people’s nonverbal sensitivity, namely their ability to decode nonverbal cues in general, will help them make accurate predictions over the stimuli persons’ real behavior in dictator game. However, we found a negative relation between nonverbal sensitivity and participants’ accuracy in estimating stimuli persons’ behavior. The negative correlation is explained due to interaction effect between nonverbal sensitivity and cognitive style: people who tend to use more analytical ways to approach information are more accurate in decoding stimuli’ behavior and have higher scores on nonverbal sensitivity too. Thus, the way individuals treat information is an important predictor for their accuracy in reading interpersonal situations.

Bibliography

AMBADY, Nalini, BERNIERI, Frank J., and RICHERSON, Jennifer A., „Toward a histology of social behavior: judgmental accuracy from the thin slices of the behavioral stream”, Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 32 (2000): 201-271.

AMBADY, Nalini, „The perils of pondering: Intuition and thin slice judgments”, Psychological Inquiry 21/4 (2010):271-278.

AMBADY, Nalini, HALLAHAN, Mark, and ROSENTHAL, Robert, „On judging and being judged accurately in zero-acquaintance situations”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69/3 (1995): 518-529.

AMBADY, Nalini, KRABBENFOFT, Mary Ann and HOGAN, Daniel, „The 30 sec. scale: Using thin slices judgments to evaluate sales effectiveness”, Journal of Consumer Psychology 16/1 (2006): 4-13.

AMBADY, Nalini, ROSENTHAL, Robert, „Half a minute: Predicting teacher evaluations from thin slices of nonverbal behavior and physical attractiveness”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 64(1992): 431-441.

AMBADY, Nalini, ROSENTHAL, Robert,„Thin slices of expressive behavior as predictors of interpersonal consequences: a meta-analysis”, Psychological Bulletin 111/2 (1993): 256-274.

BALCETIS, Emily, DUNNING, David and MILLER, Richard L., „Do collectivists know themselves better than individualists? Cross-cultural studies of the holier than thou phenomenon”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 95/6(2008): 1252-1267.

BARDSLEY, Nicholas, „Dictator game, giving. Altruism or artifact?” Experimental Economics 11(2008): 122-133.

BEKKERS, Réne, „Measuring altruistic behavior in surveys. The all-or-nothing dictator game”, Survey Research Methods 1 (2007): 139-144.

BERNIERI, Frank J., GILLIS, John S., „Personality correlates of accuracy in a social perception task” Perceptual and Motor Skills 81(1995): 168-170.

BERNIERI, Frank J., GILLIS, John S., DAVIS, Janet M. and GRAHE, Jon E., „Dyad rapport and the accuracy of its judgment across situations: A lens model analysis”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 71(1996): 110-129.

BRANAS-GARZA, Pablo, „Poverty in dictator Games. Awakening solidarity”, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 60 (2006): 306-320.

BRANAS-GARZA, Pablo, „Promoting helping behavior with framing in dictator games”, Journal of Economic Psychology 28 (2007): 477-486.

CACCIOPO, John T., PETTY, Richard E., „The need for cognition, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology”42 (1982): 116-131.

CAMERER, Colin F., THALER, Richard H., „Ultimatums, dictator and manners”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9 (1995): 200-219.

ECKEL, Catherine C., GROSSMAN, Philip J., „Altruism in Anonymous Dictator Games”. Games and Economic Behavior, 16 (1996): 181-191.

EKMAN, Paul, O’SULLIVAN, Maureen, „Who can catch a liar?” American Psychologist 49/9 (1991): 913-920.

EPLEY, Nicholas, DUNNING, David, „Feeling holier than thou: A self-serving assessments produced by errors in self – or social perception?” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 79/6 (2000): 861-875.

EPSTEIN, Seymour, „Cognitive-experiential self-theory”, in Lawrence Pervin (editor), Handbook of Personality Theory and Research: Theory and Research (New York: Guilford Publications, 1990), 165-192.

EPSTEIN, Seymour, PACINI, Rosemary, DENES-RAJ, Veronika and HEIER, Harriet, „Individual differences in intuitive-experiential and analytical-rational thinking styles, „ Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 71/2(1996): 390-405.

FISKE, Susan T., TAYLOR, Shelley E., Social Cognition (2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill 1991).

FRANK, Robert H., Passions with Reason (Ontario: Penguin Books Canada 1988).

HALL, Judith A., BERNIERI, Frank J., Interpersonal Sensitivity. Theory and Measurement (Mahwah: Lawrence Erbaum 2001).

IVAN, Loredana, „Cognitive style and nonverbal sensitivity. Cognitive-experiential self theory validation”. Revista Română de Comunicare şi Relaţii Publice 3 (2011):10-27.

MÖLLER, Jens, SAVYON, Karel, „Not very smart, thus moral: dimensional comparisons between academic self-concept and honesty”, Social Psychology of Education, 6 (2003): 95-106.

PACINI, Rosemary, EPSTEIN, Seymour, „The relation of rational and experiential information processing styles to personality, basic beliefs, and the ratio-bias phenomenon”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 76/6(1999):972-987.

ROSENTHAL, Robert, HALL, Judith A., DIMATEO, Robin M., ROGERS, Peter L. and ARCHER, Dane, Sensitivity to Nonverbal Communication. The PONS Test. (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press 1979).

VAN LANGE Paul A., SEDIKIDES, Constantine, „Being more honest but not necessarily more intelligent than others: Generality and explanations for the Muhamad Ali Effect”, European Journal of Social Psychology 28 (1998): 675-680.

VAN LANGE, Paul A., DE BRUIN, Ellen, OTTEN, Wilma and JOIREMAN, Jeffrey, „Development of prosocial, individualistic, and competitive orientations: theory and preliminary evidence”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 4 (1997): 733-737.

VAN LANGE, Paul A., KUHLMAN, Michael D., „Social value orientations and impressions of partner’s honesty and intelligence; a test of the might versus morality effect”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67/1 (1994): 126-141.

VOGT, Dawne S., COLVIN, Randall C., „Interpersonal orientation and the accuracy of personality judgments”, Journal of Personality, 71 (2003): 267-295.

NOTE

1 Acknowledgements, This work was supported by the strategic grant POSDRU/89/ 1.5/S/62259, Project ‘Applied social, human and political sciences. Post-doctoral training and post-doctoral fellowships in social, human and political sciences’ co-financed by the European Social Fund within the Sectorial Operational Program Human Resources Development 2007–2013.

2 Van Lange, De Bruin, Otten, and Joireman, „Development of prosocial”,773.

3 Paul A. Van Lange, Ellen De Bruin, Wilma Otten, and Jeffrey Joireman, „Development of prosocial, individualistic, and competitive orientations: theory and preliminary evidence”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 4 (1997): 733-737.

4 Nicholas Bardsley, „Dictator game, giving. Altruism or artifact?” Experimental Economics 11(2008): 122-133.

5 Jens Möller, Karel Savyon, „Not very smart, thus moral: dimensional comparisons between academic self-concept and honesty”, Social Psychology of Education, 6 (2003): 95-106

6 Paul A. Van Lange, Michael D. Kuhlman, „Social value orientations and impressions of partner’s honesty and intelligence; a test of the might versus morality effect”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67/1 (1994): 126-141.

7 Nicholas Epley, David Dunning, „Feeling holier than thou: A self-serving assessments produced by errors ,in self – or social perception?” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 79/6 (2000):

861-875.

8 Paul A Van Lange, Constantine Sedikides, „Being more honest but not necessarily more intelligent than others: Generality and explanations for the Muhamad Ali Effect”, European Journal of Social Psychology 28 (1998): 675-680.

9 Emily Balcetis, David Dunning, and Richard L. Miller, „Do collectivists know themselves better than individualists? Cross-cultural studies of the holier than thou phenomenon”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 95/6(2008 ): 1252-1267.

10 Van Lange, Kuhlman, „Social value orientations”, 128.

11 Van Lange, Sedikides, „Being more honest”, 678.

12 Nalini Ambady, Mary Ann Krabbenfoft, and Daniel Hogan, „The 30 sec. scale: Using thin slices judgments to evaluate sales effectiveness”, Journal of Consumer Psychology 16/1 (2006): 4-13.

13 Nalini Ambady, Robert Rosenthal,„Thin slices of expressive behavior as predictors of interpersonal consequences: a meta-analysis”, Psychological Bulletin 111/2 (1993): 256-274.

14 Nalini Ambady, Frank J. Bernieri, and Jennifer A. Richerson, „Toward a histology of social behavior: judgmental accuracy from the thin slices of the behavioral stream”, Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 32 (2000): 201-271.

15 Frank J Bernieri, John S Gillis, „Personality correlates of accuracy in a social perception task” Perceptual and Motor Skills 81(1995): 168-170.

16 Frank J. Bernieri, John S. Gillis, Janet M. Davis, and Jon E. Grahe, „Dyad rapport and the accuracy of its judgment across situations: A lens model analysis”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 71(1996): 110-129.

17 Nalini Ambady, Robert Rosenthal, „Half a minute: Predicting teacher evaluations from thin slices of nonverbal behavior and physical attractiveness”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 64(1992): 431-441.

18 Robert Rosenthal, Judith A. Hall, Robin M. DiMateo, Peter L. Rogers, and Dane Archer, Sensitivity to Nonverbal Communication. The PONS Test. (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press 1979).

19 Judith A. Hall, Frank J. Bernieri, Interpersonal Sensitivity. Theory and Measurement (Mahwah: Lawrence Erbaum 2001).

20 Dawne S. Vogt, Randall C. Colvin, „Interpersonal orientation and the accuracy of personality judgments”, Journal of Personality, 71 (2003): 267-295.

21 Paul Ekman, Maureen O’Sullivan, „Who can catch a liar?” American Psychologist 49/9 (1991): 913-920.

22 Nalini Ambady, „The perils of pondering: Intuition and thin slice judgments”, Psychological Inquiry 21/4 (2010):271 -278.

23 Rosenthal, Hall, DiMateo, Rogers, and Archer , Sensitivity to Nonverbal, 146.

24 Seymour Epstein, „Cognitive-experiential self-theory”, in Lawrence Pervin (editor), Handbook of Personality Theory and Research: Theory and Research (New York: Guilford Publications, 1990), 165-192.

25 Robert H. Frank, Passions with Reason (Ontario: Penguin Books Canada 1988).

26 John T. Cacciopo, Richard E. Petty, „The need for cognition, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology”42 (1982): 116-131.

27 Susan T. Fiske, Shelley E. Taylor, Social Cognition (2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill 1991).

28 Rosemary Pacini, Seymour Epstein, „The relation of rational and experiential information processing styles to personality, basic beliefs, and the ratio-bias phenomenon”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 76/6(1999):972-987.

29 Rosenthal, Hall, DiMateo, Rogers, and Archer , Sensitivity to Nonverbal, 53.

30 Nalini Ambady, Mark Hallahan, and Rosenthal Rosenthal, „On judging and being judged accurately in zero-acquaintance situations”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69/3 (1995): 518-529.

31 Seymour Epstein, Rosemary Pacini, Veronika Denes-Raj, and Harriet Heier, „Individual differences in intuitive-experiential and analytical-rational thinking styles, „ Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 71/2(1996): 390-405.

32 Loredana Ivan, „Cognitive style and nonverbal sensitivity. Cognitive-experiential self theory validation”. Revista Română de Comunicare şi Relaţii Publice 3 (2011):10-27.

33 Catherine C. Eckel, Philip J. Grossman, „Altruism in Anonymous Dictator Games”,. Games and Economic Behavior, 16 (1996): 181-191.

34 Réne Bekkers, „Measuring altruistic behavior in surveys. The all-or-nothing dictator game”, Survey Research Methods 1 (2007): 139-144.

35 Colin F. Camerer, Richard H. Thaler, „Ultimatums, dictator and manners”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9 (1995): 200-219.

36 Pablo Branas-Garza, „Promoting helping behavior with framing in dictator games”, Journal of Economic Psychology 28 (2007): 477-486.

37 Pablo Branas-Garza, „Poverty in dictator Games. Awakening solidarity”, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 60 (2006): 306-320.

LOREDANA IVAN

– Lector univ. dr., SNSPA, Facultatea de Comunicare şi Relaţii Publice, cercetător postdoctoral, Facultatea de Sociologie şi Asistenţă Socială Universitatea din Bucureşti. Ultima carte publicată: Loredana Ivan, Alina Duduciuc, Comunicare nonverbala si constructii sociale, București, Editura Tritonic.

sus

|