|

Politici de integrare a migranţilor

Roma migrations in Central and Eastern Europe:

from the Middle Ages until nowadays

A case study of Czech-Slovak Roma migration

trends and flows

WADIM STRIELKOWSKI

[Charles University in

Prague]

Abstract:

This paper is concerned with the

ethnical aspects of migration. Specifically, it

tries to explain the migration decisions of an

ethnical minority on the example of Roma in Central

and Eastern Europe. The study describes the history

of Roma migration from its origins until today.

Additionally, the paper focuses on a case study of

Slovak Roma asylum migrations to the Czech Republic

in 1999-2006 and analysis the socio-economic reasons

and outcomes of these migrations. We find that Roma

migrations might have very different grounds:

alongside with economic they can be social,

cultural, etc. We also find that „push factors”

explain Roma migration better than economic

incentives.

Keywords: Migration; economics of migration;

ethnicity; Roma; demographic trends; Central and

Eastern Europe; transition economies

Introduction

The paper investigates whether Roma asylum migrations in the Czech Republic in 1999-2006 were influenced by „push” or „pull” factors1 of migration. This case was chosen due to the two main reasons: (a) Czech Republic and Slovakia boast one of the largest Roma communities relative to the total population (EUMC, 2005), (b) Roma migrations in these two countries were popularized by the mass media and used by the politicians to draw attention from Roma minority issues. Therefore, it seems interesting to view this problem from a slightly different (economics) angle.

Ethnicity and migration overlap

In economic literature, ethnical origin has an impact on both the economic performance and composition of emigrants in a given country (Ritchey, 1976; Trovato and Halli, 1983; Borjas, 1994; and Borjas, 1999). Borjas’s analysis of different ethnic groups of emigrants concluded that: „the decline in immigrant economic performance (in the U.S.) can be attributed to a single factor, the changing national mix of the immigrant population” (Borjas, 1999).

Different ethnic groups tend to have different incentives for migration and are subjected to different push and pull factors. Point-based systems for immigrants (such as the one introduced in Canada in 1961) proved to attract more skilled immigrants (Baker and Benjamin, 1994).

In the case of the Central and Eastern European countries (CEECs) it has to be noted that Roma migrate between countries with similar level of economic development (high payoff to human capital). All of them are transition economics burdened by the communist heritage. Roma in CEEC usually accept unskilled jobs with a minimum wage and rarely try to invest in education of self-improvement. Therefore, Roma in CEECs are likely to constitute the least skilled immigrant workers moving between the countries in the region and usually earn less than the „majority” population. This fact is often attributed to the existence of economic discrimination but the more plausible explanation for that is that Roma earn less not because of discrimination but because they are less skilled.

The history of Roma migrations in CEECs: from the Middle Ages until nowadays

Roma trace their origin to India where they first appeared about 3500 years ago as an ethnic called the Dom. After the conquest of India by the Indo-European tribes, the Dom became one of the lowest casts in the Indian hierarchy: their typical occupational domains were professions like sewage cleaners, fur and skin sellers, bear handlers and the like. Around the 11th century AD, some small groups of Roma had started to move through Persia and Syria to the Balkans, from were they were spreading all around modern Europe.

The first record of Roma in what is now Czech Republic and Slovakia dates back to the late Middle Ages. Emilia Horvathova, a Slovak gypsiologist, states that Roma first entered Bohemia via Hungary with the army of the king Andrew II (1205-1235) after he returned from the Crusade in the Holy Lands in 1217-1218 (Horvathova, 1962). When the Tatars invaded Hungary in 1241 (and especially after the defeat of King Bela IV at Muhi) Roma fled to Bohemia to escape the butchery (Crowe, 1995). According to a prominent Czech gypsiologist Eva Davidova, the first undisputed reference to Roma comes from 1399 at the Book of Executions of the Lord of Ruzomberok where a certain Gypsy is mentioned as a member of a robber band (Davidova, 1970).

First Roma settlers in the Czech Republic and Slovakia were musicians, metal workers and warriors in the armies of Hungarian kings. They managed to co-exist with the original population in peaceful atmosphere. It was not, however, until the Hungarian army defeat at Mohacs on the 28th of August 1526 that strong anti-Gypsy policies started to emerge. The general public started to view Roma as „the spies of Tatars” or „the fifth column” and they were banned from traditional professions and limited in their travels. The anti-gypsy legislation was issued in Moravia in 1538 by king Ferdinand I Habsburg as a result of fears of Turkey military power and the destabilization caused by the Protestant wars. This was the period when all Roma troubles had began: regarded as outlaws both by Christians and Muslims (Muslim Turks considered Christians and Jews to be „people of the book” while Roma were severely exterminated), driven out of the cities, suspected of espionage, crimes and theft they began to wear a label that was to remain on the ethnic for centuries.

Austrian emperors Leopold I and Joseph I issued decrees proclaiming Roma to be outlaws („vogelfrei”) and ordering mass hunts and killings. Maria Theresa first ordered all Roma to be driven out from the land (1749) and then outlawed the use of word „Cigan” and decreed them to be called „new citizens” or „new Hungarians” (Crowe, 1991). Her enlightening policies for Gypsies included the creation of Roma settlements, census taking and placing Roma children in foster homes, schools or jobs. In 1780, there were 43 609 Roma in Slovakia (only males were counted) and Hungary, this figure dropped to 38 312 in 1781 but rose to 43 778 in 1782 as a result of Joseph’s II policies of emancipation and Serfdom Patent (Horvathova, 1962).

After the revolutions in Europe in 1848 and the creation of Austrian-Hungarian Empire, most Roma stayed in Hungary and were exposed to magyarization. The data on those who remained in Bohemia are scarce.

After the WWI and the declaration of Czechoslovak independence in 1918, all Roma were given Czechoslovak nationality ipso facto. According to the 1921 Czechoslovak census, there were 61 Roma in Bohemia and 7 967 in Slovakia (Davidova, 1970). According to specialists the census was based on „mother tongue” and therefore was not precise because the 1924 census recorded 18 257 Roma in Kosice region and 11 066 in Bratislava region (Horvathova, 1962).

The mid-war period was marked by various reforms aimed to improve the life conditions of peasants in Slovakia including Roma. Nomad passes were issued for them and notorious law No. 117 described special measures how to treat „nomadic Olasti Rom” and „people living by nomadic style” (for instance requiring them to ask permission to stay on the lands or prohibiting them from entering some spaces such as spas) (Davidova, 1970). There were several attempts to organize schools for Roma children or commit them to sports (for instance the creation of a football club SK ROMA), however the new Czechoslovak Republic had many other problems to face.

After the Munich Treaty, occupation of Czechoslovakia by Nazi Germany and the outbreak of the WWII, those Roma remaining in Bohemia (now called Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia) suffered the most (their fate being similar to that of the Jews), while those living in Slovakia (independent Slovak state) found themselves in a more tolerant environment.

Roma labour camps of Lety and Hodonin were created in 1941. Many Roma found their death there, in Auschwitz or Buchenwald. The Roma Holocaust (Porajmos) took away from 6 000 to 8 000 Roma originating from the Czech lands and few hundreds of their more fortunate Slovak compatriots. According to the Census carried out in 1947, there were 84 438 Roma left in Slovakia and 16 752 Roma in Bohemia (Necas and Miklusakova, 2002).

The post-war period was marked by the Communist takeover in the 1948 and the interest to Roma minority was bleak. In 1950 Czechoslovak president Gottwald called up a commission to find a solution for „Gypsy question”. A report on „Position of Individuals of Gypsy origin in the Work Process” was published, however not a single major effort was taken until 1958, when the Communist party published a declaration demanding „unconditional solution to the Gypsy question” and dividing all Roma into three categories: nomad, semi-nomads and completely sedentary. Those of nomadic and semi-nomadic nature were then subjected to the Law No.74 (October 1958) „On Permanent Settlement of Nomadic People”. In addition to that (perhaps to avoid the charges of racism) Roma recieved a special status of socio-ethnic group which only widened the gap between them and the Czechs and Slovaks. In 1965, the Communist party prepared a long-range assimilation plan crowned by the Ordinance No. 502 (June 1965) which prescribed „full-employment of all Gypsies, liquidation of Gypsy illegal settlements and dispersion of the Roma all around Czechoslovakia” (Crowe, 1995). However the plan failed due to the growing resentment towards the Roma presence in the Czech lands, inadequate funding and Roma unwillingness to live in Bohemia and Moravia.

In the 1960s, Czechoslovakia had one of the largest Roma populations in the Socialist Bloc. The data from 1967 estimated 223 993 Roma in the country (with 164 526 in Slovakia and 59 467 in the Czech lands) (Ulc, 1990). Interrupted by the occupation of Czechoslovakia, the campaign of Roma assimilation continued in the 1970s under the rule of the new party leader Gustav Husak. It included more severe policies, including sterilization of Roma women for financial benefits offered by the local health workers and intended to reduce Roma birth rate (the average number of live births for a Czechoslovak woman was 2.4 and for Roma woman it was 6.4) (Srb, 1985).

Roma population grew from 219 554 in 1970 to 288 440 in 1980, a 31.4 per cent increase, while the general population grew by only 6 per cent during the same period. The Roma population in the Czech Republic grew by 47 per cent during the 1970s and the 1980s, while the same for Slovakia was 25.5 per cent (Necas and Miklusaková, 2002). Clearly, some fears of over-population of Gypsies were quite common within the general public which resulted in day-to-day discrimination and despise. In the same time, there began an increase in the Roma population in Bohemia caused by the destruction of Roma housing in Slovakia and forced movement of Gypsies to Bohemia and by voluntarily movements of Gypsies searching for better economic opportunities and higher standard of leaving. During the 1970s and 1980s, over 4 000 Roma dwellings were destroyed in Slovakia (Necas and Miklusakova, 2002).

Another part of the assimilation campaign led by the government was forced education of Roma youngsters. In 1971, only 10 per cent of eligible Roma children in Czechoslovakia attended kindergartens. Throughout the 1970s the number of Roma children graduating from schools rose from 16 per cent to 25.6 per cent (Crowe, 1995). Generally, school drop-out rate was increasing with the grade and only a third of Gypsy children finished eights grade in 1983-1984, while merely 4 per cent went on to University (Ulc, 1990).

Gypsy employment during the period of assimilation policies was a mixture of failure and success: in 1981 in Czechoslovakia 87.7 per cent of male Roma (91.9 per cent average for the Czechoslovak males) and 54.9 of female Roma (87.7 for Czechoslovak females) were employed. In addition, 80 per cent of all Roma were in low-paid and low-skilled jobs (in agriculture, construction and industry) (Crowe, 1995).

The Velvet Revolution on the 17th of November 1989 and the liberalization of economic, social and political life brought two different effects for the Roma minority: alongside with the opportunity for the Roma to form their own political and cultural organizations, a new atmosphere for open expression of the prejudice towards Roma was created.

After the collapse of the Communist regime the government estimated that there were some 400 000 Roma in Czechoslovakia, a 36 per cent increase for over a decade. A sharp rise in crime level (by 52 per cent in the Czech Republic and 17 per cent in Slovakia) that engulfed Prague (by 181 per cent in Prague alone in 1990) and Bratislava, a thing unknown in the times of the police state maintained by the „iron hand” of the Communists, was attributed to Gypsies, especially those 18 years old and younger (Orbman, 1991). This resulted in skinhead attacks that were the main reason the Rom emigrating to Canada and the UK were declaring in the asylum forms.

Before the formal separation of Czechoslovakia in 1993, Slovakia had an estimated Gypsy population of 400 000, and Czech Republic had 150 000 (Crowe, 1995). In anticipation of a breakup of a federation a number of Slovak Roma began to move to the Czech lands because they felt the political and social atmosphere would be more tolerant there, and economic conditions better. This sudden move was a surprise for many Czechs who attributed a sharp increase in crime by 90 per cent as caused by these migrations. In addition, after the separation of the Czechoslovakia, the majority of Roma in the Czech Republic by 1993 became Slovak citizens due to the strict citizenship criteria.

In general, Roma living standard in the Czech Republic can be regarded as those superior to the ones in Slovakia. This, in combination with lower wages, social and racial segregation and chronic debts many Gypsy families have, led to the natural trend of inducing more or less substantial migrations of Slovak Roma to the Czech Republic. The report of International Organization for Migration (IOM) on emigration of Slovak Roma to the Czech Republic states that migration waves could have reached some 10 000 Roma in the 2000-2003 (IOM, 2003). However, opened borders and the customs union between Czech Republic and Slovakia established after the split-up of the Federation together with Roma secrecy and disbelief in authorities made it very difficult to obtain the real data on their migrations.

The situation of Roma minority in other Central and Eastern European countries after the fall of Communist regimes was quite similar to the one in Czechoslovakia as presented above: Roma were viewed as the symbol of all gone awry in the new democracies of the Eastern Europe (Crowe, 1995). These attitudes were often fuelled by the fears of Roma population immense growth rates that usually outnumber those of the national „majority” as well as blaming Roma for the threatening crime rates.

Overall, if the problems of Roma community in several CEECss are compared, there are some similarities. First of all, due to the poor education Roma were the first to loose jobs when large socialist companies were downsizing after the collapse of Communist regimes in 1989-1991. This contributed to high unemployment and growing social deprivation amidst Roma minority. Second, as a result of economic downfall and growing social unrest in the former CEE Communist countries, Roma often became a target for racially-motivated „ventilating” attacks. Third, in spite of efforts to establish in politics, Roma representatives were not capable of putting together a considerable political force. Fourth, as a result of institutional changes, the majority of Roma found themselves at the margins of the society which led to further social deprivation, growth of usurers’ networks and finally to choosing migration as the only solution.

Roma migration from Slovakia to the Czech Republic after the split-up of Czechoslovakia

Prior to 2000, there were no major Roma migrations from Slovakia to the Czech Republic (Roma migrations within former Czechoslovakia started as the reaction to the Czech Citizenship Law adapted in 1993 which denied Czech citizenship for people with Slovak federal citizenship (O’Nions, 1999) and affected about 77 000 Roma (Tolerance Foundation, 1994b)).

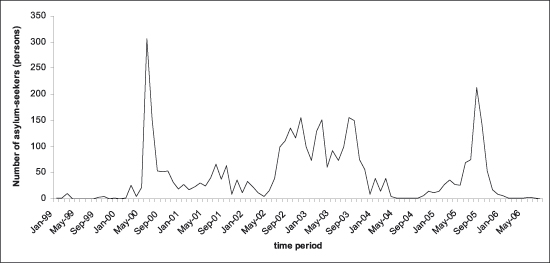

Chart 1: Slovak (Roma) asylum-seekers in the Czech Republic in 1999-2006

Source: Czech Statistical Office, 2006 and Ministry of Internal affairs of the Czech Republic, 2006.

According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM, 2003), factors that influence Roma migrations from Slovakia into the Czech Republic can be split into push and pull factors (Table 1).

Table 1: Major push and pull factors influencing emigration of Slovak Roma to the Czech Republic in the 20

| Push factors |

Pull factors |

Increase of racially-motivated attacks in Slovakia |

Difference between the unemployment rate in the Czech Republic and Slovakia |

Increase of unemployment in Slovakia |

Dynamics of minimal hourly minimal wage in the Czech Republic |

Dynamics of social welfare in Slovakia (for instance, the decrease of the maximum amount of social welfare benefits per one family to 10500 SKK) |

Dynamics of social welfare benefits in the Czech Republic |

Source: IOM, 2003, own compilation

Further, all factors influencing migrations of Slovak Roma to the Czech Republic can be further divided into three main groups according to their nature of impact: social, cultural and economic factors (Table 2).

Table 2: Economic, social and cultural factors influencing emigration of Slovak Roma to the Czech Republic in the 2000s

| Social factors |

Cultural factors |

Economic factors |

Decrease in welfare benefits (from 1 January 2003 to max. 10 500 SKK) |

Family networks (long-term connections to relatives in the Czech Republic) |

Social welfare benefits (proves to be insignificant) |

Employment opportunities (typical for Eastern Slovakia) |

Usurer networks (asylum benefits to repay the loans) |

Paid medical care (small payments in hospitals, can pile up at 500-600 SKK per month) |

Spatial segregation (Roma settlements in Slovakia) |

Status and social structure (migration of the lower-middle strata) |

Difference in unemployment in Slovakia and the Czech Republic (employment is higher in the West) |

Discrimination (racial and employment) |

Conflict (escaping the conflict situations) |

Deprivation (claustrophobic environment of ghettos and settlements) |

Source: IOM, 2003, own compilation

When it comes to the types of migration of Slovak Roma, IOM report (IOM, 2003) distinguishes four basic types of immigration (Table 3).

Table 3: Basic types of immigrants: Slovak Roma migrations to the Czech Republic in the 2000

| Types of immigration |

|

Unregistered immigrants |

Singles or deprived individuals (often teenagers and orphanage-leavers) who are not interested in supporting their families in Slovakia and thus do not try to look for employment. Use relatives as base and source of pocket money, engage in petit crime: stealing, drug dealing and the like |

Temporary labour migrants |

Roma workers come back home in short intervals and also send the majority of their income back to their families. In many cases, temporary labour immigration has seasonal nature |

Asylum seekers |

Popular amongst Slovak Roma in the 2000s. Most of the applications were rejected by the Czech authorities but the long waiting process (up to 2 years), free housing and accommodation, and modest employment opportunities made it attractive nevertheless. |

Multiply immigrants |

Migrating to take care of the elders or children. In many cases there are Roma born and raised in the Czech Republic but given Slovak citizenship after the split-up of the Czechoslovak federation. Numerous groups of unsuccessful asylum-seekers who returned from the Western Europe or North America. |

Source: IOM, 2003, own compilation

Empirical model

As far as no precise data on Slovak Roma legal and illegal migrations exists (for ethical reasons), we had to use the data on Slovak asylum seekers assuming that most of them were Roma. The data was obtained from the Czech and Slovak Statistical Office and Statistics of the Ministry of Internal affairs of the Czech Republic and Slovak Republic. The data is of time-series nature. The empirical model is based on similar studies (Walsh, 1974; Helliwell, 1997; O’Donoghue and Strielkowski, 2006) and it can be written as the following:

AMi = β0 + β1Y (ATTSK ,USK)PUSH + β2Y (MWCZ ,BCZ)PULL + ui i =1,2, …, n (1)

where AMi is the number of asylum-seekers from Slovakia in the Czech Republic in 1998-2006, Y(ATTSK ,USK)PUSH is the cumulative of „push” factors which consist of a number of racially motivated attacks and Slovakia in 1998-2006 (ATTSK) and the number of unemployed in Slovakia (USK). Y(MWCZ ,BCZ)PULL is a cumulative of „pull” factors of migration which consist of the dynamics of hourly minimum wage in the Czech Republic (MWCZ) and dynamics of social welfare benefits in the Czech Republic (BCZ).

Table 4: Determinants of Slovak Roma asylum migration to the Czech Republic

| Push factors |

AM

std. errors |

Pull factors |

AM

std. errors |

Number of racially-motivated attacks in Slovakia, ATTSK |

5.056***

[.877] |

Dynamics of hourly minimal wage in the Czech Republic (in CZK), MWCZ |

-13.466***

[4.171] |

Unemployment in Slovakia (thousands of people), USK |

1.135***

[.320] |

Dynamics of social welfare benefits in the Czech Republic (in thousands of CZK), BCZ. |

-.00003***

[8.34e-06] |

Constant |

732.007** [265.083] |

N |

34 |

R-squared |

0.89 |

Note: Robust standard errors in brackets; * significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1%; Source: own estimations.

The results are presented in table 4 above. What is to be noted are the highly-significant coefficients of the first two variables (push factors of migration). Especially the number of racially motivated takes in Slovakia has a considerable influence on the increase of Slovakia Roma asylum migrations. The influence of the variable representing the unemployment in Slovakia on Roma asylum migrations has been expected, therefore the sign of its coefficient and it significance have been anticipated.

The remaining two pull factors, dynamics of hourly minimum wage in the Czech Republic and dynamics of social welfare benefits in the Czech Republic, are also highly significant, however they have a negative influence on the dependent variable. Perhaps this can be explained by the impossibility to undertake full-time jobs for asylum seekers. The improvement of labour markets situation (higher hourly wages) in the Czech Republic led to the increasing competition amongst different social groups (workers from Ukraine, Vietnam or Poland) which discouraged Slovak Roma from undergoing the asylum-seeking procedure in the Czech Republic. Additionally, the improvement of socio-economic situation in the Czech Republic probably made some of the Slovak Roma to consider other forms of migration (temporary labour migration or moving to re-unite with distant relatives using Roma social networks).

The important conclusion that comes from the empirical model presented above is that the only satisfying explanation of Roma asylum migrations from Slovakia to the Czech Republic is push factors of social and economic nature. This can be clearly seen from the results of the model estimation: the most important determinant of Roma asylum migrations appears to be an increase in the number of racially-motivated attacks in the source country.

Conclusions

It is quite clear that different ethnic groups use different approaches to migration. An example of Slovak Roma asylum-seekers in the Czech Republic makes it clear that economic incentives (and pull factors) account for just a small proportion of reasons for migration of various ethnic groups (including asylum migrations). Worsening of economic and social conditions in the source country explain Roma migrations better.

Nevertheless, Slovak Roma propensity to migration is pre-determined by quite a large number of factors. First of all, Roma willingness to change the place of residence stems not only from their ethnic background or cultural specifics but rather from the historic necessity: in former Austrian-Hungarian emprise and later Czechoslovakia Roma minority has always been persecuted and outlawed; changing the place of residence became an integral part of survival. Second, it might be that the Roma are tempted to solve all the problems merely by moving to another destination.

Roma seem to be very sensitive to the development of social situation in their „home country”. In case the social and economic situation is worsening and Roma feel threatened by this development, their immediate response would be emigration, even if this emigration involves undertaking an unpleasant procedure of asylum migration.

References

BAKER, Michael and BENJAMIN, Dwayne, „The performance of Immigrants in the Canadian Labour Market”. In Journal of Labour Economics, 12, 369-405, 1994.

BORJAS, George, „The Economics of Immigration”. In Journal of Economic Literature 32, 1667-717, 1994.

BORJAS, George, „Knocking on heaven’s door”. Princeton University Press, 1999.

BORJAS, George, „Immigration and Welfare Magnets”. In Journal of Labour Economics 17(4): 607-637, 1999

Český statistický úřad. Statistické ročenky České republiky (1993-2006). Praha,

www.czso.cz

CROWE, David, A history of Gypsies of Eastern Europe and Russia. I.B. Taurus Publishers, London, 1995.

DAVIDOVA, Eva, „The Gypsies in Czechoslovakia. Part I: Main Characteristics and Brief Historical Development”. Translated by D.E. Guy. In Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society, Third Series. Vol. 69, no. 3-4, 1970.

DAVIDOVA, Eva, „Cesty Romů”. Vydavatelstvíi Univerzity Palackého, Olomouc, 1995.

European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia (2005). EUMC annual report 2005 (http://eumc.eu.int).

HELLIWELL, John, „National borders, trade and migration”. NBER Working paper No. 6027, 1997.

HORAKOVA, Milada, „Labour migration trends in the Czech Republic during the last decade”. RILSA, Praha, 2005.

HORVATHOVA, Emilia, „Cigani Cigáni na Slovensku”. Bratislava, Vydavetel’stvo Slovenskej Akademie vied, 1962

Infostat – Institute of Informatics and Statistics (2002), Projection of Roma population in Slovakia until 2025. Bratislava, Akty

International Organization for Migration (2003), Zprava o analyze soudobe migrace a usazovani prislusniku romskych komunit ze Slovenske republiky na uzemi Ceske republiky. Retrieved from

www.iom.cz

Ministry of the Internal Affairs of the Czech Republic (2004), Zprava o situaci v oblasti migrace na uzemi CR za rok 2003, Praha, Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Czech Republic,

www.mvcr.cz

NECAS, Ctibor and MIKLUSAKOVA, Marta, „Historie Romů na území České republiky”. Cesky Rozhlas, Retrieved from http://romove.radio.cz/cz/clanek/18785, 2002

ORBMAN, Jan, „Crime Rate among the young”. Radio Free Europe Research, Vol. 12. no. 32, 1991

OSCE/ODIHR (2000), The report on the Reasons of the Migration of the Roma in the Slovak Republic. Vienna.

RITCHEY, Ronald, „Explanations of migration” in Annual Review of Sociology, no.2, 363-404, 1976

SHAW, R. Paul, „Migration theory and Fact”. Philadelphia, Regional Science Institute, 1975.

SRB, Vladimir ,„Zmeny v reprodukci ceskoslovenskych Romu” in Demografie, 30, no. 4, 305-309, 1985.

Štatistický úrad Slovenskej republiky (2000), Štatistická sprava o základních vývojových tendenciách v hospodarstve SR, č.1, Bratislava..

Štatistický úrad Slovenskej republiky (2005), Vyvoj obyvatelstva v SR. Bratislava.

O’DONOGHUE, Cathal and STRIELKOWSKI, Wadim, „Ready to go? EU Enlargement and Migration potential: lessons for the Czech Republic in the context of Irish migration experience” in Prague Economic Papers, Vol.1, 14-28, 2006.

Tolerance Foundation (1994a), Report on Czech Citizenship Law. Prague: Tolerance Foundation,

www.ecn.cz.

Tolerance Foundation (1994b), Analysis of 99 cases. Prague: Tolerance Foundation,

www.ecn.cz

TROVATO, Frank and HALLI, Shiva, „Ethnicity and Migration in Canada” in International migration review, Vol. 17. No. 2, 1983.

UN Common database. World Bank, 2005.

ULC, Ota, „Communist National Minority Policy: The case of the Gypsies in Czechoslovakia” in Soviet Studies, Vol. 2, no. 4, 1990.

WALSH, Brendan, „Expectations, Information and Human Migration: Specifying an Econometric Model of Irish migration to Britain” in Journal of Regional Science Vol. 14, 107-120, 1974.

1

„Push” and „pull” factors are the terms used in sociological and demographic

literature. Amongst „push” factors are worsening of living conditions in the

home country, „pull” factors usually include emigrants’ expectations to

obtain higher earnings as well as to improve their economic (and social)

well-being in the country of immigration.

WADIM STRIELKOWSKI – Assistant Professor of Economics, Institute of economic studies, Faculty of social sciences, Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic.

sus

|