|

Sfera Politicii

The Social

Democrat Party and the use of political marketing in

the 2016 elections in Romania

CLAUDIU MARIAN

[Babeș-Bolyai

University]

Abstract:

The 2016 parliamentary elections were a

turning point in political campaigning in

Romania. With the major changes brought to the

law on political campaigns and party financing,

the political parties searched new avenues to

reach out effectively to voters. Our analysis

focuses on the political campaign conducted by

the Social Democrat Party (PSD) and closely

investigates their political strategy, branding,

targeting and the communication tools used

during the 2016 parliamentary campaign, in order

to identify the main approach changes and which

communication tools were the most effective. To

get our answers we centralize and compare the

social media activity (FB posts, online

campaigns), the activity on the television and

the major outdoor campaigning elements - banners

and posters. Also, we took into account the

precampaign period used to increase awareness

and to gently integrate the main political

message among the voters.

Keywords:

Elections;

political campaign; political strategy;

communication tools; social media

Introduction

In the last decades, social-political life in Romania has changed significantly. The process of transition, from communism to democracy, imposes new challenges of both economic and political nature. Political entities have had to adapt to an increasingly competitive context and have been forced to adopt behavior that satisfies the voters’ claims. Nevertheless, daily practice has shown that in the first two decades of post-communism, access to power was more important than providing a credible and sustainable political product. Political parties often adopt campaigning strategies focused on voters already loyal and the efforts to make the voters more responsible and involved and to attract new supporters were fragmented and short-term oriented. Targeting was mainly done at local level and most of the time was not based on an integrated national strategy, this if we talk about parliamentary or presidential elections held at national level. The electoral campaigning period is strictly limited, according to the law, to the thirty days before the election, and in all that time the voters are assaulted by propaganda messages, attacks between political competitors, intrigue and unsubstantiated promises. In the past decades, civil society was often inert or represented by interest groups with biased objectives and interests.

The research done so far shows that, from a political and social perspective, we still have to deal with a division of the voters by their localization (urban environment vs. rural environment), with a stabilization of the party system, with a relative volatility of the electorate and with a low democratization of political party leadership selection. In all this dynamic political environment, and at the same time hampered by uncompetitive practices and customs inherited from the past, current political parties have to transform their strategies and permanently adapt to the social and demographic changes of the electorate. Strategies must respond to the new limitations of available resources and at the same time convey a clear positioning of the political entity. Moreover, with the emergence of new voters’ categories, targeting should also include younger generations whose political choices are not specifically defined, as is the Romanian case.

2016 parliamentary elections – general perspectives and a wider context

The 2016 parliamentary elections have been marked by major changes in practice and the current approach. On the one hand, they have taken place in a new legislative framework, which has led to a return to a party-list voting system and proportional representation. Moreover, the electoral threshold was changed, one deputy being elected for every 73.000 inhabitants, with 3.000 more than the level imposed by the old electoral law. At the Senate, the level was increased from 160.000 to 163.000 citizens. Although the electoral threshold remained unchanged, it could be calculated in two ways: either by reporting the 5% to the total validly expressed votes at national level, or by calculating the 20% of the valid votes cast in at least four constituencies for all electoral competitors, this being an alternative threshold. As a result, after twelve years since the 2004 elections, the voting system went back to the old habits (list voting), marking the failure of the uninominal voting system, which implies candidates for each electoral district and in the same time is keeping the proportionality of party representation in the legislature. The voting system introduced in 2008 brought with it an “anomaly“ of the law, so that the difference between the two main ranked political competitors was so great that it came back to a situation registered in 1990 and the absolute majority of the Liberal Social Union (USL) obtained in 2008 led to an unprecedented situation. The new Legislature resulting from the 2012 elections reached 588 deputies and senators, and because 283 mandates were won by an absolute majority, to the Parliament (following the seats redistribution formula) were added an additional 79 mandates of deputy and 39 senatorial seats, thus reaching the highest number of elected politicians that has ever existed since 1989 in the supreme forum of democracy. http://revistapolis.ro/alegerile-generale-pentru-parlamentul-romaniei-din-2016-reflectate-in-presa-internationala-teme-analize-interpretari/ - _ftn3

The general elections of 2016, in addition to a new electoral system, took place in a special internal context, unprecedented after the collapse of communism. Since November 2015, the Parliament has supported a technocratic executive, a solution adopted by the political forces at that time, following a general consensus, determined by the tragedy of the “Collective“ club. After this event and following the consequences that led to the blockade of the Victor Ponta Social Democratic Party government, the international press was skeptical about the radical transformation of the Romanian political system as a whole. In addition to this event, the 2016 election and the pre-election period were marked by the theme of the anti-corruption fight, a phenomenon that debuted after 2005 and has grown in recent years. Even on the election’s day, Le Figaro publishes an analysis that synthesizes that Romania’s general objective of the elections was precisely affirmed as being the corruption, the election offering the answer to the choice of the Romanian society for the coming years.

More than this, under the technocrat government leaded by Dacian Cioloș (17 November 2015 – 4 January 2017), the level of trust recorded at social level was permanently decreasing. An analysis conducted by INSCOP Research (in 2016) showed that 58,8% (April 2016) of the population considers that things were getting worse and Romania is leaded in a wrong direction – compared with 52,3% in November 2015. In that time, as presented by the research, 45,6% of the citizens answered that the main problem at national level is represented by the low economic development and the lack of jobs (at that moment the unemployment rate was 6,8 percent – both in 2014 and 2015 – as reported by Eurostat in 2016). Corruption, even if it was a largely debated subject in the last two decades and considered a major issue at national level, was placed on the top of the list only by 25,3% of the respondents.

From another perspective, in a social research conducted between august 2015 and august 2016, the president of Romania, Klaus Iohannis, lost 26% in terms of popular support (until 35%), while on the top was listed Victor Ponta (former leader of the Social Democrat Party - PSD) with 42% (Avangarde, 2016). The voter’s intention and political support was distributed mostly between the two major parties – PSD with 38% and National Liberal Party (PNL) with 29%.

Having in mind the context presented above and the general political situation in Romania in the years before the 2016 parliamentary elections, the local elections organized in 5th of June 2016 must be mentioned. Then, the Social Democrat Party got 37,58% of the votes, while PNL got 30,64% (data gathered from National Electoral Bureau). Overall, the situation remained unchanged, if we compare it with the results from the local elections of 2012. Only that, then, PSD and PNL, worked together, under the name USL (The Social Liberal Union) to overcome the influence of the Democrat Liberal Party (PDL). At local level, the influence of PSD was only strengthened after 5th of June, and despite the fact that they registered some defeats, the politically controlled area became more consistent and it was easier for the leadership to project influence.

The campaigning process in that time was no different from the previous local elections, most of the work being done by the local politicians and without any coordination at national level. Only that it was for the first time when the changes of the electoral law had to be respected. The new provisions were challenging, having in mind the old way campaigning was done. It was forbidden to use and distribute electoral materials, such as pens, clothing, flashlights, buckets etc. and the public shows, celebrations and fireworks with political purpose were not allowed. Banners, mobile billboards, advertising screens, light advertising and vehicle advertising were also banned. More than this, the posters had to be smaller than those in other campaigns – at most 50cm by 35cm and they had to be displayed only in designated places established by the mayor`s order. Also, the electoral posters combining colors or other graphics signs that can evoke or suggests national symbols of Romania were denied (established by Law 115/2015 & Law 208/2015, Law 113/2015).

To all these, another major factor in reshaping the political strategy and the campaigning process might be represented by the presidential elections of 2014. Then the social media played an important role and influenced in a consistent way the results. Iohannis won the elections by using the same pattern of communication as Obama and its political campaign manage to reach the voters disinterested in elections in general. Even if Victor Ponta (PM at that time and head of PSD) had a FB page since 2010 and Iohannis got his own only in May 2014, the winner still recorded better effectiveness of the delivery of the message. The rise of Iohannis` popularity through social media, might have been a very good lesson for PSD, and the changes identified in the following campaigns organized by the social democrats could come from that moment.

As such, in the following sections we will present the political strategy, the branding process and the communication tools used by PSD in the parliamentary elections campaign of 2016 and we will try to identify which of the used instruments were the most effective.

The new approach of political marketing

Even if in the post-communist Romania, PSD won mostly all the time the parliamentary elections, those organized in 2016 were different in terms of political campaigning and political strategies. It looks like they learned from the presidential elections of 2014 and from the more recent experience in the local elections. The result got them 45,47% of the votes, while PNL got only 20,04%, a very low score if we consider the trends. The only moment when PSD was elected by more voters was the 2012 elections when they were allies with PNL. So, the question that can be asked is How they did it? What was done better? To get the answers we will focus our attention on political campaign organized and conducted by the biggest party in Romania.

The message and the program

The political campaign conducted by PSD in the parliamentary elections of 2016 was based on a larger strategy emerged in the elections for the European Parliament of 2014. Then the central message was based on two key phrases: ,,Proud to be Romanian“ and „Romania – strong in Europe“. These nationalist approaches were complemented by traditional symbols and were used to send a strong message to the voters. More than this, the other parties had a weaker approach: PNL tried to get votes by using slogans as ,,Support the EuroChampions“ or ,,EuroChampions to deeds“, while Popular Movement Party marched with ,,The movement makes the change. We raise Romania“. Even if the photos used for the banners and other outdoor advertising elements were bought from a specialized website (shutterstock.com) and they were presenting scenes from Belarus or Poland, the scandal did not affect significantly the success. Also, there were adverts promoting the idea that the coalition of 2012 between PSD and PNL is still alive, and it was delivered through the message ,,USL is alive“, inducing a certain amount of doubt for the untrained voters, even if it was banned in short time.

On the other hand, in the local elections of 2016, PSD did a smaller effort to secure the winning. This because, at least in the rural areas, the chances to lose the seats were reduced and in most of the cases the politicians were not running for the first time.

But in November 2016, the strategy was different. PSD continued the nationalist approach. The main political message was ,,Dare to believe in Romania“, even if after few days the idea promoted by PNL was almost similar: ,,Dare to believe in Romania leaded by honest people“. Even though the electoral law explicitly denied the right to use graphic elements that can be assimilated to national symbols, PSD`s colors used in almost all the graphic designs were red, yellow and blue. Like this, it was made sure the resemblance with the national flag, although in the Constitution is specified that the Romanian flag is blue, yellow and red, but for the regular voter did not made the difference. Moreover, the message was developed under the advice of the two Israeli campaigning strategists: Moshe Klughaft and Sefi Shaked, and it is similar with the one used by Mitt Romney in his 2012 presidential race („Believe in America“).

Regarding the program, this was designed to fit ,,like a glove“ the elements generating insecurity within the majority of the voters and presented above. PSD promoted a more developed middle class, bigger wages, fair pensions, better medical services and an improved educational system. Also, they promised the elimination of 102 non-fiscal taxes, alongside with greater support for the local farmers, reindustrialization and well-paid jobs in strong Romanian companies. Overall, the program is characterized by a nationalist approach and is based on a multitude of economic figures and deadlines. Also, it leaves the impression that is elaborated based on very realistic analyses and gives the feeling of feasibility.

More than this, it addresses problems that occur in several categories of voters: young voters (lack of jobs, poor income, unemployment, economic instability), retired workers (fair pensions, medical services, lower taxes), entrepreneurs (lower or cut taxes, governmental financial support, reduction of bureaucracy, prevention) as also farmers (no more delays in payment of subsidies, rebuilding the irrigation system, improved procedures for accessing the EU funds, lower taxes and a better promotion of the local products). The party proposes enough salary and pension increases to maintain credibility within the traditional sympathetic group and adds a dose of nationalism through the idea of re-industrialization and the Sovereign Investment Fund, whose role is unclear but should have a significant economic impact. At the same time, tax reduction, 18% VAT and tax cuts are an attempt to attract an audience that is traditionally associated with the PNL and perhaps even those who are attracted by the anti-system rhetoric promoted by Save Romania Union (USR). Also, the program stands out through its size – 9029 words, compared with PNL`s program which has 3400, and despite its dimension there are no mentions related to corruption reduction, administrative reform, poverty reduction, minorities rights, foreign policy, inflation rate, etc.

From political perspective, the PSD is riddled with major integrity issues, but the program is in accordance with the behavior adopted in 2012, when it acts as an anti-austerity party and this remains their biggest message. In the popular vocabulary, voters often make the difference between the political parties relying on the following logic ,,They took from us“ vs. „They gave us“. The last one is often associated with PSD, and this because, for example, between 2012-2015 the party negotiated with its political partners to increase the minimum wage several times and cut the VAT for staples and medicine. All these, in a decade of economic growth and fast recovery after the 2008 recession.

Delivering the message

All the observations from above are supporting the statement that PSD is a program-oriented party. As noted by Ban in his article Romania: a social democratic anomaly in eastern Europe? – 2016, „the Social Democrats are one of the region’s most resilient and effective political formations. Critically, the institutional infrastructure of the PSD remains highly competitive: the top of the party hierarchy has real authority and its reach on the ground has no counterpart. This comes with the usual pork barrel politics feeding the party-municipal government networks and their known neo-patrimonial pathologies, but a third of the country still lives and votes in villages and, come election time, it is a huge asset to have these local party institutions“. But still, in 2016, PSD managed to reach more voters from different social categories and it obtained the support from those unaffiliated. A social research conducted by IRES showed that PSD got the vote from 33,5% of those between 18 and 24 years old, 28,5% from those between 25 and 34 yo, and from 37,6% of the voters having between 35 and 44 years old. Moreover, in terms of education level, PSD was voted by 59,6 percent of those with basic education, 46,4% from those with high school education, and by 26,8% of the voters having higher education – university and above. These values denote an extension of the support obtained from non-traditional voters, if compared with the voters’ profile from the previous elections.

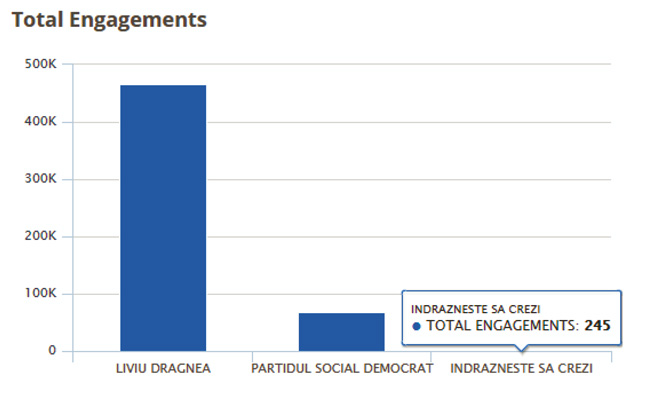

First of all, the new communication tool used in the campaign of 2016 was the social media. The message was delivered mostly through Facebook, and the strategy was very well planned. There were three elements that have been remarked: the Facebook profile of the party`s leader – Liviu Dragnea, the PSD official page on the same platform and the website www.indraznestesacrezi.ro/. By these instruments, PSD dominated the online environment during the campaign period.

An overall analysis provides the following parameters for the campaigning conducted using the social media tools. For better understanding the dimensions of the political competition, we considered also the official pages of PNL, USR and PMP (Popular Movement Party), the other three main political competitors.

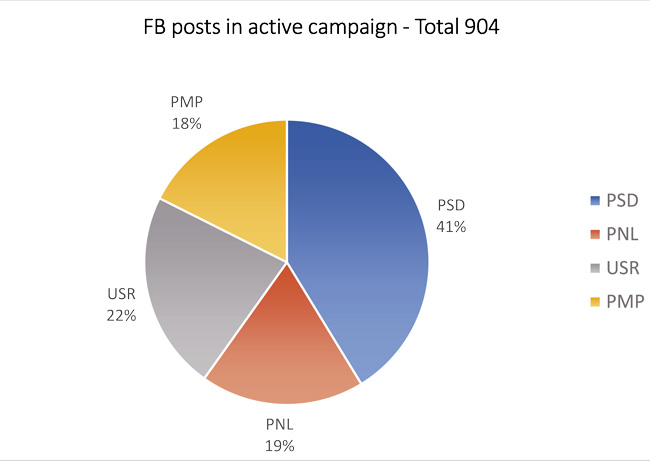

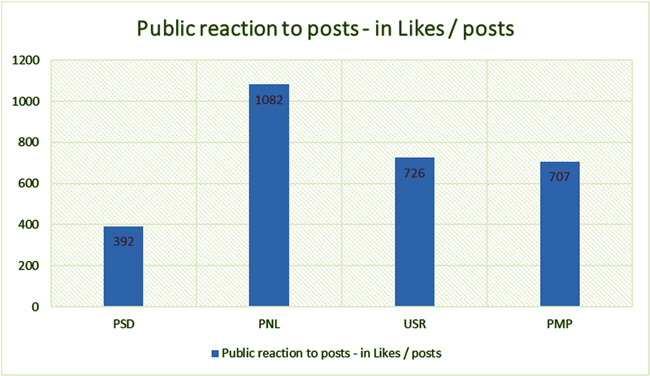

Thus, regarding the FB posts in active campaigning period, we registered a total amount of 904 messages of which: 373 (41%) from PSD, 168 (19%) from PNL, 204 (23%) from USR and 159 (18%) from PMP. Were considered all the messages, both text and media, posted on the official FB pages.

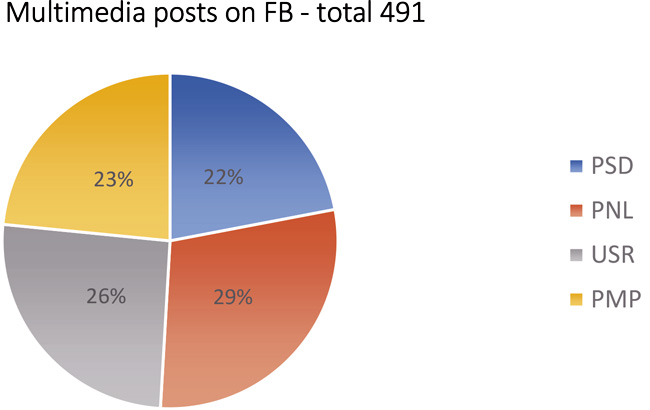

The media content promoted via Facebook was marked by relatively equal efforts, the majority of the videos and photos being uploaded by PNL, representing 29% of 491 uploads. PSD assumed 22% of the total, but the party generated and promoted video content in an extensive way through the website www.indraznestesacrezi.ro/. There, 523 videos received from the supporters were uploaded and shared on various Facebook pages. More than this, PSD not only had the official page of the party, but each local and regional branch used its own page to promote the political message at local level. USR published 126 posts having photos or videos, representing 26% of the total, while PMP tried to reach the voters through 115 multimedia messages.

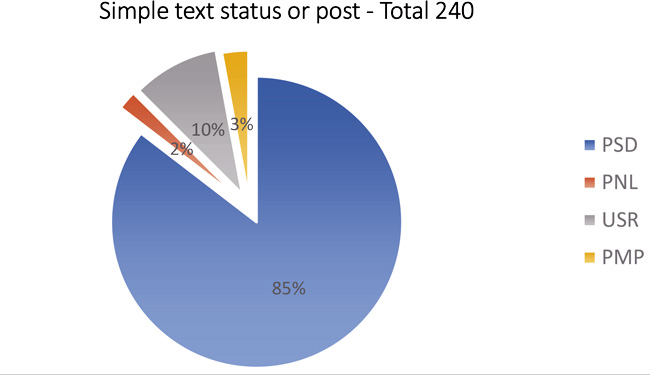

The simple text messages and statuses have been extensively used by PSD. A total of 240 entries were taken into account, of which 205 were generated by PSD. In this case PNL had only 5 interventions, being overtaken by USR with 23 and PMP with 7.

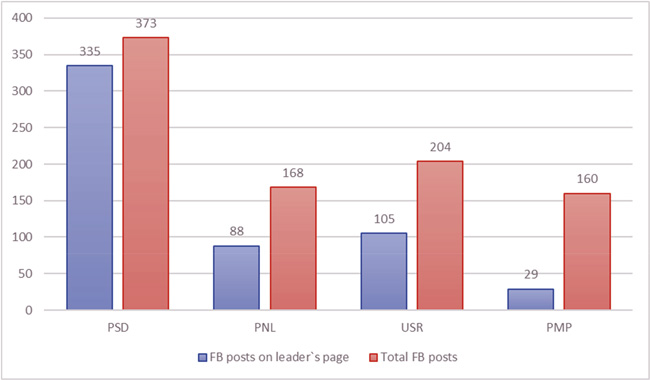

While almost all the parties had a second page, representing the leader, the proportion of integration of the official page with the leader`s profile differs from case to case. For example, PSD used both pages to promote the program and the party`s supporters (through videos), making it easier for the voters to identify themselves with the broader community. 335 messages and multimedia content has been shared both on the official page and on the profile page of Liviu Dragnea. None of them was about the individuals but about the program, the political product, the community and all of them were design to motivate the supporters to vote. On the other side, PNL had 88 posts on leader`s page out of the entire amount – 168. USR was more active 105 out of 204 posts being delivered through the leader`s page. Regarding the PSD, they integrate both profiles mentioned above with the website indraznestesacrezi.ro, dominating the online environment.

Even if PNL had around 1082 like/post and PSD only 392 likes/post, the impact was way higher for the content promoted by the social democrats. The videos were intensively shared and even though the users did not land on the official pages they have interacted in a one way or another with the promoted message. In many ways, a “share“ is even better than a “Like“ because it represents a much stronger social endorsement and is far more likely to get noticed in the newsfeed of the friends of the person who has shared (it is called the network effect). Sharing means that your supporters are proactively telling the world about how great your content is. Moreover, those not directly interested with supporting the PSD, after they got in touch with the adverts, had the impression that the organization is credible, organized and it can adapt to new social contexts. On the other hand, PNL was unable to deliver the message in an effective way, even to their traditional supporters, and the liberals based their efforts on the charisma of Dacian Cioloș (active PM in that time), which was not officially affiliated with the party.

As such, in the political campaign for the parliamentary elections of 2016, PSD dominated the on-line environment both qualitatively and quantitatively, reaching more people and attracting new supporters, all these by better interacting with the users. Another factor that raised the efficiency of the process might be represented by the general approach: to intensively promote the program and the proposed measures with deadlines and technical details instead of the image of the leader.

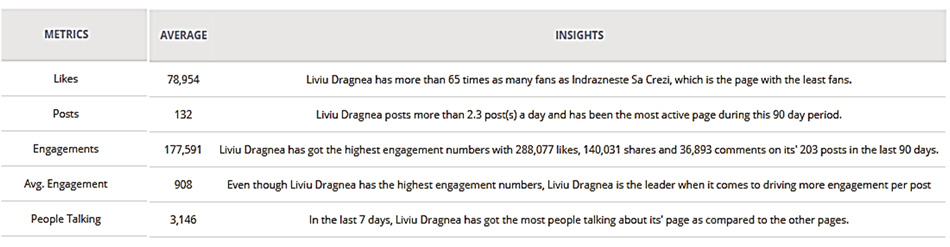

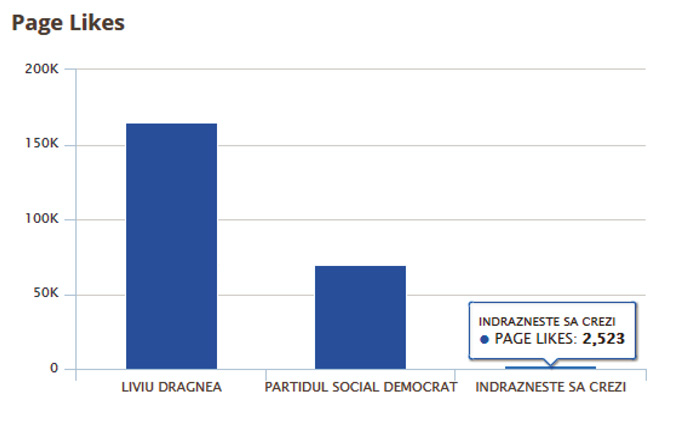

A comparative analysis, containing the three Facebook pages: Liviu Dragnea, PSD and Îndrăznește să crezi, provided us the following correlates. The period we consider was represented by 90 days, starting with 2nd of September 2016.

The overall analysis demonstrates the level of integration of social media tools used by PSD. The message generated at the national level was distributed predominantly through the party leader’s page, and was taken over by local organizations and disseminated among the supporters. The general impression was that of coordination and integrated efforts. Moreover, even those who were not advanced users of Facebook platform have been able to interact with the promoted media content and this because it was promoted by acquaintances and not by a dull political entity. The voting decision was also influenced by the quality of the promoted materials, the simplicity of the message and the fact that the idea of voting with the party was not annoyingly promoted, but to vote and support a project for the entire country.

On the other hand, PSD also sent the political message to voters who did not belong to the Internet user’s category. The electoral program was synthesized in leaflets and brochures that were distributed in the mailboxes of the citizens. The message was clear and concise and focused on the economic welfare the political program will bring. Moreover, the idea of efficiency and responsibility was promoted. Figures were the central element, and they all conveyed that citizens would have more money in their pockets. An interesting initiative was to involve the electorate by inviting them to keep the campaign newspaper in order to mark the moments when the political commitments will be put into practice.

Also, in the leaflets were presented graphs showing the economic development of Romania and the growth periods under the leadership of PSD were highlighted. Moreover, in order to increase credibility, it was mentioned that the data were provided by the National Institute of Statistics. The distribution of printed materials has been done nationwide and the local PSD affiliated authorities have been concerned that the message will reach every citizen. However, there are no available statistical data on the number of distributed materials or the areas where they were predominantly delivered.

Regarding the presence on television, all the speeches were based on the same economic data that will improve the lives of the Romanians. Moreover, the PSD has benefited from the support of the tv channel Antenna 3, which has been concerned with the electoral campaign and intensively disseminated and debated the political proposals. It is well known that Antenna 3 is promoting a nationalist-minded approach and do not hesitate to support euro skeptic attitudes and behaviors. Their journalists do their best to keep up the nationalist spark within their viewers and in the shows are always inviting celebrities and personalities who promote themselves as being patriots or „real Romanians“. More than this, the political debates are only focused on one side of the subject and when different opinions are presented they are cornered. It is widely accepted that Antenna 3 openly supports PSD an its political partners, having a significant impact within the voters from rural areas and those politically unawares.

Another factor was the absentee voter. Having in mind that there was a stable PSD electorate, the parties on the right intended to increase participation. This was not effective, even though there was enthusiasm and optimism among the young voters. The inspired PSD migration to the center politics, started by Victor Ponta, when Tony Blair’s team advised him to broaden the middle-class electoral pool, was continued by Liviu Dragnea, which has raised seductive promises for various neglected categories until then, from farmers, doctors to small entrepreneurs. In this regard, the mobilization in the urban area, much higher than in other years, has not automatically helped the right. In contrast, the liberals seemed to bet more on slogans than on concrete initiatives.

Conclusions

The political campaign of the PSD in the 2016 parliamentary elections was based on a different approach. The electoral strategy had as its central element the political message and the program, and the tools used to disseminate them were different. Learning from the presidential election of 2014 and the local elections of 2016, the party sought to attract new supporters and rely on the needs of the electorate. Moreover, it was intended to better integrate the efforts and the intention was to develop a clean campaign, also due to the new legislative regulations limiting the action field. Not being able to offer promotional items and grandiose performances, social democrats based their strategy on figures and promises for a wealthier Romania.

The opposition was inert, PNL being unable to outline an effective strategy and to deliver a valid political message. The strategy used by PNL was a very poor one. It was 100% based on the image of Prime Minister Dacian Ciolos, which was a bet that could bring many points, but was not enough. The promoted leader was not running and was not officially associated with the party. Being the only figure that counted, he was vulnerable to attacks, especially because he had no one to support his back. PNL had no charismatic leader. In the back was only Alina Gorghiu – the president of the party, who was not a prominent figure. More than this, the PSD, took advantage of previous protests and publicly manifested dissatisfaction, and adopt a rhetoric which was placing Dacian Cioloș alongside occult forces from the West that would like to destabilize Romania.

The message of national unity and the economic promises that will bring wealth and prosperity to the voters were the driven elements of the strategy used by the social democrats. The party was able to disseminate the political vision and to attract new supporters. The use of social media and the conventional communication tools ensured a significant success in the elections.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Alina Neagu, „Presa din Israel: Campania electorală a PSD, coordonată de consultanți israelieni“, Hotnews, 18.12.2016.

2. Andra-Ioana Androniciuc, „Using Social Media In Political Campaigns. Evidence From Romania“, SEA - Practical Application of Science 10 (2016).

3. Charles Thiefaine, „La corruption, enjeu des législatives roumaines“, Le Figaro (2016),

https://www.lefigaro.fr/international/2016/12/11/01003-20161211ARTFIG00021-la-corruption-enjeu-des-legislatives-roumaines.php

4. Cornel Ban, „Romania: A Social Democratic Anomaly in Eastern Europe?“, OpenDemocracy și EUVisions (2016),

https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/can-europe-make-it/romania-social-democratic-anomaly-in-eastern-europe/

5. Cristian Preda, „Partide, voturi și mandate la alegerile din România (1990-2012),“ Studia Politica: Romanian Political Science Review 12 (2013): 27-110.

6. Cristian Vaccari, „Social media and political communication“, Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica 43, 3 (2013).

7. Daniel Bochsler, Sergiu Gherghina, „The shakedown of the urban-rural division in post-communist Romanian party politics“, ECPR Joint Sessions, Workshop on “The Nationalisation of Party Systems in Central and Eastern Europe“ (2008).

8. Declan P. Bannon, „Relationship Marketing and the Political Process“, Journal of Political Marketing 4, 2-3 (2005).

9. Donald Green, Partisan hearts and minds: Political parties and the social identities of voters (Yale University Press, London, 2002).

10. Ed Pilkington, Amandra Michael, „Mitt Romney`s campaign closing gap on Obama in digital election race“, The Guardian, 14.06.2018.

11. George Jiglau, Sergiu Gherghina, „The Divergent Paths of the Ethnic Parties in Post-Communist Transitions“, Transition Studies Review 18, 2 (2011).

12. INSCOP, „INSCOP - Adevărul despre România“ (2016),

https://www.inscop.ro/7-aprilie-2016-agerpres-sondaj-inscop-psd-38-pnl-372-daca-duminica-viitoare-ar-fi-alegeri-parlamentare

13. Ioan Popescu, „Looking back at 2015: Colectiv, the Romanian tragedy that has changed laws and people“, Romania-Insider.com.

14. Ionela Gavril, Anca Pandea, „Evoluția sistemului de vot în România, la alegerile parlamentare de după 1989“, Agerpres (2016),

https://www.agerpres.ro/flux-documentare/2016/11/06/evolutia-sistemului-de-vot-in-romania-la-alegerile-parlamentare-dupa-1989-05-25-02

15. IRES, „Surprize în portofoliul alegătorului. De cine a fost votat PSD“, Digi24 (2016),

https://www.digi24.ro/stiri/actualitate/politica/alegeri-parlamentare-2016/ires-profilul-alegatorului-de-la-scrutinul-de-duminica-631028

16. Jackson Lilleker, Political campaigning, elections and the Internet (London:Routledge, 2011).

17. Mădălina Mihalache, „Mesajul „USL trăiește“ interzis de CNA“, Adevărul, 22.05.2014.

18. Monica Pătruț, „Candidates in the presidential elections in Romania (2014): the use of social media in political marketing,“ Studies and Scientific Researches. Economics Edition 21 (2015): 127-135.

19. R.M., „PSD face campanie sub sloganul „Mândri că suntem români“cu poze din Belarus și Polonia“, Hotnews, 30.04.2014.

20. Sergiu Gherghina, Clara Volintiru, „A new model of clientelism: Political parties, public resources, and private contributors“, European Political Science Review 9, 1 (2017).

21. Sergiu Gherghina, Mihail Chiru, „Romania: An Ambivalent Parliamentary Opposition“, în Elisabetta De Giorgi, Gabriella Iolnszki (ed.), Opposition Parties in European Legislatures: Responsiveness Without Responsibility?, (Abingdon:Routledge, 2018).

22. Sergiu Gherghina, Mihail Chiru, Între ideologie și strategie : programele partidelor pentru alegerile legislative naționale 2016 (Cluj-Napoca: CA Publishing, 2018).

23. Sergiu Gherghina, Sorina Soare, „A test of European Union post-accession influence: comparing reactions to political instability in Romania“, Democratization, 23, 5 (2016).

|