Context

Student achievement can be determined by many factors within the educational context. The literature focus on factors related to students, teachers, school resources, family background and official or hidden curriculum. Studies in the sociology of education have primarily focused on social-class differences in education. Following King (2007), we recognize that Weberian treatment of class chances in education could be an impo rtant starting point in the analysis of gender and social class inequalities in education. Education is to be understood as a resource for which individuals and groups compete[2]. We approach the subject from a sociocultural perspective, which states that knowledge (including the official school knowledge), and gender are socially constructed[3]. Also, the concept of power is important since there are historical power relations that disadvantage most women and most working class individuals, and favor most men and those in the middle class.

Education plays an important role in earning higher earnings. Hatos[4] demonstrates that graduating from a university in Romania makes your income 30% higher compared to those who only finish high-school. At the same time, parents and students must pay to benefit from the opportunities offered by the educational system. Therefore, while on the one hand education determines better earning opportunities, it is the latter which can guarantee a better education. After the collapse of the communism in 1989, education system reform became one of the political priorities at that time. The curriculum reform was conducted in different time phases, starting from the reparatory phase of changes in education ideology, and continuing with the construction of a new curriculum. This was followed by the introduction of alternative textbooks and the change in the nature of evaluation[5]. Until the late `90s, the discussions about equality of opportunity were only framed within the public discourse. The researchers who formulated recommendations for public policies suggested that „it is necessary to apply the principles of social equity and equality of chances in education no matter the social background, ethnicity or intellectual capacity“[6].

In the area of the sociology of education researchers focus on understanding how school structures influence students. They ask questions about the impact of education on graduate students, or about the phenomenon of social and cultural reproduction, which takes place throughout the education system[7]. Generally, the fundamental research question in the sociology of education is: „What causes social-class inequalities in achievement at school and what can be done about it?“.[8] Social, economic, and cultural factors prevent some individuals to perform well in school and therefore implicitly hamper the chances to obtain important occupational positions, as there is a strong connection between the individuals` education and positions in the post-industrial society.

This paper contributes to the understanding of the role that family background plays in reading achievement for primary school students in Romania. We assume that reading achievement is related to academic achievement later in school. Reading achievement is considered a competence or a form of linguistic capital[9], which is of particular importance in the first years of schooling. The paper is also important in the context of the sui-generis transition process in post-communist Romania. Rado[10] considers that the rapid change from a society with a high degree of anticipation to the unpredictable post-communist Romania was difficult to manage by the population and thus adaptation was not easy. Also, the increasing economic inequalities in the last 20 years[11] affected an important part of the population who started to question the efficiency of the education system in overcoming the problems related to equality of opportunity. We think that class is predominantly gendered and that the intersection between class, gender and ethnicity can determine the reproduction of inequalities in academic achievement.

Reproduction theories developed on the challenge of the functionalist perspective. Scholars in the functionalist tradition believe that the capitalist society is based on meritocracy, and education is a decisive factor considered by headhunters later on[12]. This contestation started with debates about the official curriculum, which was considered an instrument that serves the interests of those who have power. Moreover, there were claims that the system helps the privileged groups perform better in school and maintain control over others[13]. Bourdieu and Passeron[14], Bernstein[15] and Apple[16] argue that the organization of knowledge, the ways in which it is transmitted and the evaluation process are of crucial importance in the reproduction of class relation in capitalist societies.

In the work of Bowles and Gintis[17] correspondence theory is at the core of their analysis. They emphasize that there is a correspondence between the structural relations in the capitalist society and those in school settings. In other words, there is a direct connection between school and workplace. Bourdieu and Passeron[18] describe the process of cultural reproduction, arguing that the concept of cultural capital is a form of knowledge transferred from one generation to another through families and schools, connecting the former to the official curriculum. Therefore, the acquisition of knowledge is influenced by family background and by the pedagogic activities of the parents. Some families construct a pedagogic context and at the same time, they introduce their children to the `official pedagogic communication`[19]. Bernstein`s theoretical work[20] provides an important framework for analyzing how the linguistic codes used in school disadvantage the members of the working class students. Apple[21] pleads against „the racially gendered, class-specific nature of knowledge as evidenced in the ways it privileges the voices of dominant groups“. There is no doubt that analyzing how school contributes to the reproduction process needs a more complex research design that cannot be developed in the present paper. This analysis will focus on the equality of opportunity, as defined by Coleman: „A fourth type of inequality may be defined in terms of consequences of the school for individuals with equal backgrounds and abilities. In this definition, equality of educational opportunity is equality of results, given the same individual input“[22].

Most studies were conducted in the US and UK, where the social class gap for achievement is significant, and remained constant during the last 40 years. In the UK, educational attainment is linked with parents` occupation, education and income[23]. Scholars admit that this gap is enlarged by other factors, such as race, ethnicity or gender. For example, King[24] thinks that teachers make a clear distinction between boys and girls and also distinguish between their social backgrounds. The referential `Coleman report` (1966) discovered the relatively small importance of school resources and teacher characteristics in students’ achievement. Alternatively, he highlighted the importance of family background, which he defined through factors such as family residence and mobility; parents education; the structural integrity of the family; the size of the family; the presence of reading materials at home; prevalence of in-house conversations on school issues; parents involvement in school affairs[25]. Bourdieu and Passeron (1977) argue that variables such as social origin or sex are related to language test performance. More recently a meta-analysis using the journal articles published between 1990 and 2000 found that socioeconomic status has a medium to strong effect on academic achievement[26]. For the current analysis we investigate home resources, including parents` level of education and occupation, and gender as two of the most often used predictors in relation to school performance.

Early studies of family background on school performance did not use gender as a valid explanatory variable. Besides, before 1970 most of the studies were based on boys` samples in US and UK[27]. Also, when researchers focused on gender, they studied male domination in academic achievement and in obtaining high educational qualification. Today, in Western countries, gender plays an important factor in the analysis of school performance, considering that gender gap is closing[28]. In UK, US, and Australia important studies on causes for underachievement of boys were conducted[29]. Still, this should not be interpreted as „all boys are underachievers and all girls perform well at school“. For a complete analysis it is also important to take seriously the role of class. In Romania, there is evidence that gender stereotypes affect school performance, but its manifestation varies based on the field of study. Girls achieve better than boys at humanities and boys obtain better results than girls in sciences[30]. Gender roles are strengthened by the attitudes and expectations of teachers for the subjects where boys and girls perform best. Nevertheless, curriculum is also a key element. Ștefănescu and Grunberg[31] observed that school has various instruments that perpetuate gender roles and stereotypes and identified curriculum as one of them. This has consequences not only in the educational environment for the short term (competences are developed differently, based on gender, so that certain domains become either male or female dominated) but also in the long run, as it impacts on both the public and private interactions of the individual. Researchers consider that equal opportunities in education can be guaranteed only if gender is taken into account.

Method

We use data from student background file from PIRLS 2011 for the case of Romania. PIRLS 2011 is the third cycle of Progress in International Reading Literacy Study and collects data to provide information on trends in reading achievement of fourth-grade students worldwide[32]. This test measures the ability to read for literary experience and the ability to read and use information in a pragmatic way[33]. Besides the achievement test, we use data from questionnaires answered by students, parents, teachers and school directors[34]. The authors argue that reading achievement influences the future of individuals, economic welfare, and an active participation in the society[35]. The results are reported on the PIRLS scale from 0 to 1000, but most of the time students obtain scores ranging between 300 and 700. For instance, the Romanian average for PIRLS is 502, while the best average score was obtained by Hong Kong (571).

We analyzed some of the most important predictors for overall reading achievement considering the following directions: interpretation; integration; and evaluation, which we consider as influential for the future academic performance of students. The predictors are gender; home resources for reading (including parents education or parents occupation); parents reporting on their reading habits; and involvement of parents in early literacy activities with their children.

Gender Differences IN Reading Achievement

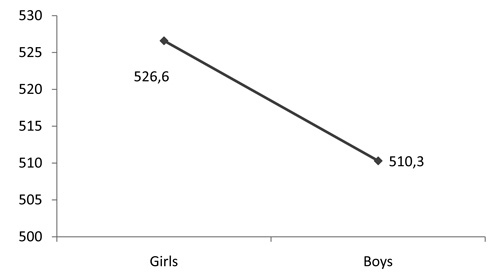

An independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare reading achievement based on gender. There is a significant difference in the reading achievement score for boys and girls: t=6,47 (df=4646)=; p<0,001: r=0,09. Girls scored somewhat higher than boys in reading achievement, which validates international results obtained during the last decade.

Home Resources

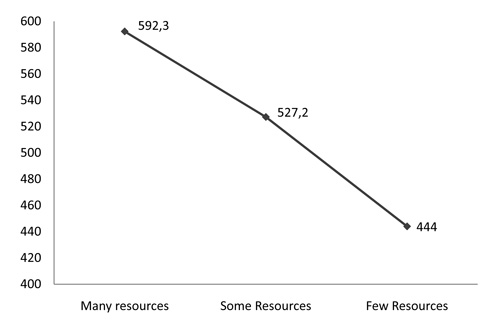

Home resources learning scale was created using: parents` education; parents` occupation; the number of books available at home; and study supports (availability of an internet connection and their own room). There is a high correlation between home resources scale and reading achievement (r=0.54, p<0.01), meaning that having many home resources increases the probability of obtaining good scores in the reading test. In other words, students living in an environment with more resources have a larger probability of obtaining higher scores at the reading test.

Also the crosstab below shows a linear pattern. Using home resources index which contains three ordinal categories created by PIRLS, we can observe that those who have a small numbers of home resources obtain smaller scores compared to those who have some or many home resources.

|

Home resources |

N |

Mean reading score |

Std. Deviation |

Std. Error |

|

Many resources |

446 |

592,31 |

58,97 |

2,38 |

|

Some Resources |

3209 |

527,24 |

74,39 |

3,78 |

|

Few Resources |

814 |

444,05 |

86,43 |

2,10 |

|

Total |

4469 |

518,58 |

85,37 |

2,47 |

A Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was computed to assess the relationship between reading achievement and the fact that the parents of students reported they like reading, on one hand, and that they engaged in early literacy activities with their children, on the other hand. First, there is a medium to high correlation between reading achievement and the fact that the parents of students report that they like reading[36] (r=0.35, p-value<0.01). Second, the same link can be observed between reading achievement and the fact that parents engaged in early literacy activities with their children before beginning primary school[37] (r=0,34.p-value<0,01). Also, there is a significant correlation between parents engaging in literacy activities with their children and reporting they like reading (r=0.54, p<0.01).

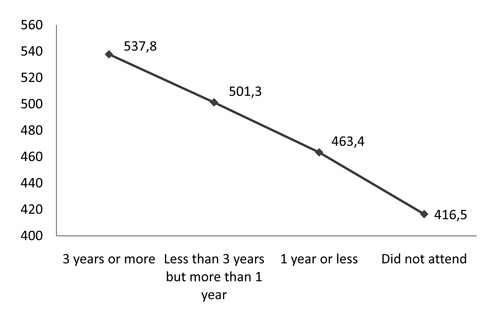

Attending pre-primary education could equally give students an early start in school. Knowing that family background has an important effect on student achievement, attending kindergarten could be an important factor in overcoming children disadvantages (see descriptive statistics below).

|

Student Attended Preschool |

N |

Mean reading score |

Std. Deviation |

Std. Error |

|

3 years or more |

2714 |

537,84 |

76,01 |

1,45 |

|

Less than 3 years but more than 1 year |

1394 |

501,38 |

84,80 |

2,27 |

|

1 year or less |

151 |

463,41 |

85,007 |

6,91 |

|

Did not attend |

235 |

416,59 |

97,007 |

6,32 |

|

Total |

4494 |

517,69 |

86,09 |

1,28 |

Bearing in mind that each of the factors mentioned above matter in the reading achievement of students, we used a linear regression analysis in order to understand the overall common effect of the predictors and to see which one important. Thus, the response variable is the overall reading achievement, while the explanatory variables are home resources scale; parents reading degree scale; involvement of parents in early literacy activities before the beginning of primary school; and gender. R-squared is 0.31, which implies that the model explains 31% of the variability of response variable around the mean. Concerning individual coefficients, the most important is home resources (Beta=0.469). All in all, results suggest that having home resources, being a girl and having parents who like reading and are co-involved in early literacy activities increases the probability of having a higher score in student reading achievement.

Response variable: Overall Reading Achievement

|

R |

R Squared |

Adjusted R Squared |

Std. Error of the Estimate |

|

,557 |

,310 |

,309 |

70,88 |

Coefficients

|

Model |

B |

Std. Error |

Beta |

t value |

Sig |

|

(Intercept) |

292,494 |

6,008 |

48,687 |

,000 |

|

|

Home resources |

19,624 |

,640 |

,469 |

30,651 |

,000 |

|

Gender (0- female; 1 male) |

-14,064 |

2,131 |

-,082 |

-6,601 |

,000 |

|

Early literacy activities before beginning primary school |

2,445 |

,546 |

,069 |

4,477 |

,000 |

|

Parents like reading |

2,796 |

,644 |

,069 |

4,344 |

,000 |

Discussion

The research was designed to explore the role of family background and gender in reading performance. The variables are part of the Progress in international reading literacy study (PIRLS). We used student background file database in PIRLS, for the case of Romania.

The results of the study revealed that home resources scale – which includes education and occupation of parents, the number of books available home, and study supports (availability of an internet connection and their own room) – is a strong predictor for reading achievement. In other words, having parents with higher education and occupations that ensure higher earnings, a big number of books at home and study support from your parents makes one more likely to obtain better results in reading achievement. Also, gender is an important variable in predicting reading achievement and girls are more likely to obtain good results than boys. This can be due to the fact that girls are generally encouraged to follow humanities, which could bring into discussion a „segregation“ process meaning that a very small number of girls choose to specialize in engineering, mathematics or informatics. The multiple causes behind this process range from individual attitudes towards these academic fields to the influence of education curriculum on individual perception of sciences[38]. The disadvantages deriving from this are mostly manifested in the choice limitations once they find themselves on the labor market. In other words, graduates with science degrees tend to earn more than graduates with arts degrees[39].

The discussion on attending pre-primary education and the engagement of parents in early literacy activities with their children before beginning primary school is also important. This influences reading achievement of students and thus the linguistic competence which is most of the time linked with academic achievement. The results show that attending kindergarten could be an important factor in overcoming children disadvantages, in the context that the social origin and family background determine to a great extent, differential chances of success and failure.

Although all factors included in this analysis are instrumental in reading achievement, home resources scale is by far the most important explanatory variable for reading achievement. Available data suggests that inequalities in social background develop during the first years of school, when it is theoretically easier to equalize reading competencies, compared to the second half of the primary school cycle and secondary school. Consequently, schools do not take the role of reading competencies equalizers, which perpetuates inequalities in opportunities for Romanian students.

Bibliography

AYALON, Hanna, „Women and Men Go to University: Mathematical Background and Gender Differences in Choice of Field in Higher Education“, Sex Roles, Vol. 48, No. 5-6, 2003, 277-290

APPLE, Michael, Ideology and curriculum, Routledge Kegan Paul, Boston, 1979

BALICA Magdalena, Voinea Lucian, Jigău Mihaela, Horga Irina, Fartușnic Ciprian, Perspective asupra dimensiunii de gen in educatie, Institutul de Stiinte ale Educatiei, Bucuresti, 2004.

BERNSTEIN Basil, Class, codes and control: Theoretical studies towards a sociology of language, Routledge, London, 1971

BERNSTEIN Basil, Class, codes and control: Applied studies towards a sociology of language, Routledge, London 1973

BERNSTEIN Basil, Class, codes and control: Towards a theory of educational transmission, Routledge, London, 1975

BERNSTEIN Basil, The Structuring of Pedagogic Discourse. Vol IV: Class, Codes and Control, Routledge, London, 2003

BLACKMORE Jill, „Educational organizations and gender in times of uncertainty“ in The Routledge International Handbook of the Sociology of Education, Michael Apple, Stephen Ball and Luis Armando Gandin (eds.), Routledge, London and New York 2010

BOURDIEU Pierre, Passeron Jean-Claude, Reproduction: In education, Society and Culture, Sage Publications, London, 1977

BOWLES Samuel, Gintis Herbert, Schooling in capitalist America: Educational reform and the contradictions of economic life, Basic Books, New York, 1976

BROWN Douglas, „Apple Michael, Social Theory, Critical Transcendence, and the New Sociology: An Essay“, In Education, Vol. 17, No. 2, 2011, 1-11

COLEMAN James, Equality of educational opportunity, U. S. Government Printing Office, Washington DC, 1966

COLEMAN James, „The concept of equality of educational opportunity“, Harvard Educational Review, Vol, 38, 1968, 7–22.

HATOS Adrian, Sociologia educației, Polirom, Iași, 2006

IVAN Claudiu, „Arhitectura instituțională din România, suport al egalității de șanse? Criterii și mecanisme sociologice explicative“, in Reconstrucție instituțională și birocrație publică în România, Alfred Bulai (ed.), Editura Fundației Societatea Reală, București, 2009

KING Ronald, „Sex and social class inequalities in education: a re-examination“, in Education and Society. 25 years of the British Journal of Sociology of Education, Len Barton (ed.), Routledge, London, 2007, 112-131

MULIS Ina et al, PIRLS 2011 International Reading Results in Reading. TIMS & PIRLS International Study Center, 2012

NASH Roy, Explaining Inequalities in School Achievement. A Realist Analysis. Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2010

PARSONS Tallcot, „The school class as a social system: some of its functions in American society“, Harvard Educational Review, Vol. 29, 1959, 297-313.

PERRY Emma, Becky Francis, The Social Class Gap for Educational Achievement: a review of the literature, RSA Projects, 2010

RADO Peter, Transition in Education: policy making and the key educational policy areas in the Central-European and Baltic countries, Open Society Institute, Budapest, 2001

SAHA Lawrence, „Sociology of Education“, in 21st Century Education: A Reference Handbook, Thomas Good (ed.), Sage, 2008

SIRIN Selcuk, „Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review of research“. Review of Educational Research Vol. 75, 2005, 417-453.

VLASCEANU Lazăr (ed.), Școala la Răscruce. Schimbare și continuitate în curriculumul învățământului obligatoriu. Studiu de impact, Polirom, Iași, 2002.

ȘTEFĂNESCU Doina Olga and Grumberg Laura, „Manifestări explicite și implicite ale genului în programele și manualele școlare“ în Școala la Răscruce. Schimbare și continuitate în curriculumul învățământului obligatoriu. Studiu de impact, Vlasceanu, Lazăr (ed.), Polirom, Iași, 2001

WAGENAAR Theodore, „The Sociology of Education“ in 21st century sociology: A reference handbook, Clifton D. Bryant, Dennis Peck (eds.), Sage Publication Inc., Thousand Oaks, California: Thousand Oaks, California, 2007

YOUNG Michael (ed.), Knowledge and control: New directions for the sociology of education, Collier-Macmillan, London, 1971

ZAMFIR Cătălin, „Ce fel de tranziție vrem? Analiza critică a tranziției II“, Raportul social al ICCV, No. 5, 2012.

NOTE

[1] This paper is a result made possible by the financial support of the Sectoral Operational Programme for Human Resources Development 2007-2013, co-financed by the European Social Fund, under the project number POSDRU/159/1.5/S/134650 with the title „Doctoral and Postdoctoral Fellowships for young researchers in the fields of Political, Administrative and Communication Sciences and Sociology“

[2] Ronald King, „Sex and social class inequalities in education: a re-examination“, in Education and Society. 25 years of the British Journal of Sociology of Education, Len Barton (ed.), (Routledge, London, 2007), 116-117

[3] Jill Blackmore, „Educational organizations and gender in times of uncertainty“ in The Routledge International Handbook of the Sociology of Education, Michael Apple, Stephen Ball and Luis Armando Gandin (eds.), (London and New York: Routledge, 2010)

[4] Adrian Hatos, Sociologia educației, (Iași: Polirom, 2006), 93-95

[5] Lazăr Vlasceanu (ed.), Școala la Răscruce. Schimbare și continuitate în curriculumul învățământului obligatoriu. Studiu de impact, (Iași: Polirom, 2002), 865

[6] Vlasceanu, Școala la Răscruce, 874

[7] Theodore Wagenaar, „The Sociology of Education“ in 21st century sociology: A reference handbook, Clifton D. Bryant, Dennis Peck (eds.), (Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publication Inc., 2007), 311-312

[8] Roy Nash, Explaining Inequalities in School Achievement, A Realist Analysis, (Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2010), 2

[9] Pierre Bourdieu, Jean-Claude Passeron, Reproduction: In education, Society and Culture, (London: Sage Publications, 1977), 72-73

[10] Peter Rado, Transition in Education: policy making and the key educational policy areas in the Central-European and Baltic countries, (Budapest: Open Society Institute, 2001), 11-15

[11] Cătălin Zamfir, Ce fel de tranziție vrem? Analiza critică a tranziției II. Raportul social al ICCV, no. 5, 2012

[12] Tallcot Parsons, „The school class as a social system: some of its functions in American society“, Harvard Educational Review, Vol. 29 (1959): 304-309

[13] Michael Young (ed.), Knowledge and control: New directions for the sociology of education, (London: Collier-Macmillan, 1971)

[14] Bourdieu and Passeron, Reproduction

[15] Bernstein Basil, Class, codes and control: Towards a theory of educational transmission, (London: Routledge, 1975)

[16] Apple Michael, Ideology and curriculum, (Boston: Routledge Kegan Paul, 1979)

[17] Bowles Samuel, Gintis Herbert, Schooling in capitalist America: Educational reform and the contradictions of economic life, (New York: Basic Books, 1976)

[18] Bourdieu and Passeron, Reproduction

[19] Basil Bernstein, The Structuring of Pedagogic Discourse. Vol IV: Class, Codes and Control, Routledge, London, 2003, 204-207

[20] Bernstein Basil, Class, codes and control: Theoretical studies towards a sociology of language, (London: Routledge, 1971); Bernstein Basil, Class, codes and control: Applied studies towards a sociology of language, (London: Routledge, 1973); Bernstein Basil, Class, codes and control: Towards a theory of educational transmission, (London: Routledge, 1975)

[21] Douglas Brown, „Apple Michael, Social Theory, Critical Transcendence, and the New Sociology: An Essay“, In Education, 17, No. 2 (2011): 4

[22] James Coleman, „The concept of equality of educational opportunity“, Harvard Educational Review, 38, (1968): 14

[23] Emma Perry, Francis Becky, The Social Class Gap for Educational Achievement: a review of the literature, RSA Projects, (2010), 5

[24] Ronald King, „Sex and social class.“, 120

[25] James Coleman, Equality of educational opportunity, (Washington DC: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1966), 298-302

[26] Selcuk Sirin, „Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: A meta:analytic review of research“, Review of Educational Research 75 (2005)

[27] Lawrence Saha, „Sociology of Education“, in 21st Century Education: A Reference Handbook, Thomas Good (ed.), Sage, 2008

[28] Saha, „Sociology of Education“

[29] Lawrence Saha, „Sociology of Education“, Emma Perry, Francis Becky, The Social Class Gap for Educational Achievement: a review of the literature, RSA Projects, 2010,

[30] Magdalena Balica, Lucian Voinea, Mihaela Jigău, Irina Horga, Ciprian Fartușnic, Perspective asupra dimensiunii de gen in educatie, (Bucuresti: Institutul de Stiinte ale Educatiei, 2004), 81

[31] Doina Olga Ștefănescu and Laura Grunberg, „Manifestări explicite și implicite ale genului în programele și manualele școlare“ în Școala la Răscruce. Schimbare și continuitate în curriculumul învățământului obligatoriu. Studiu de impact, Lazăr Vlasceanu (ed.), (Iași:Polirom, 2001), 122

[32] The description of the study can be found here: http://timssandpirls.bc.edu/pirls2011/index.html

[33] Ina Mulis et al, PIRLS 2011 International Reading Results in Reading. TIMS & PIRLS International Study Center, 2012, 6

[34] For more information visit: http://timssandpirls.bc.edu/pirls2011/international-contextual-q.html

[35] Ina Mulis et al, PIRLS 2011 International Reading Results in Reading. TIMS & PIRLS International Study Center, 2012, 1

[36] A scale according to responses from parents to seven statements about reading and how often they read for enjoyment (Mulis 2012, 10). The level of measurement of this scale is continuous.

[37] A scale according to responses from parents, to nine statements about having done activities with their children, such as playing with alphabet toys, reading out loud, writing letters or words etc. (Mulis 2012, 11). The level of measurement of this scale is continuous.

[38] Ayalon Hanna, „Women and Men Go to University: Mathematical Background and Gender Differences in Choice of Field in Higher Education“, Sex Roles, 48, (2003), 228

[39] Hanna Ayalon, „Women and Men“, 227