1. From euphoria to despair

1989. The fall of the Berlin Wall was an unparalleled moment of collective euphoria. The wave of enthusiasm swept across Europe, causing communist regimes to tumble like so many pins in a bowling alley.

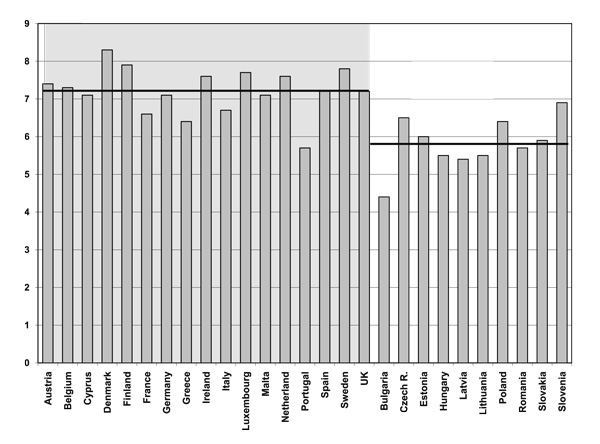

20 years later. Global studies and research concerning the subjective evaluation of happiness show without a doubt that in Europe the peoples in the former communist countries are unhappier than those in Western European countries, that their confidence in the future is at alarmingly low levels, and that nostalgia for the former totalitarian regimes has grown to a so far unthinkable extent. In World Data Base of Happiness[1], a simple comparison of the data made available for the European Union member countries (the results of scientific research carried out between 2000 and 2009) points out the clear difference between the seventeen Western states and the ten ex-communist countries (Figure 1). The mean value for happiness in the seventeen Western states of the EU is mW = 7.22, whereas the mean value for the former communist states is mE = 5.82.

Figure 1. Happiness value for the 27 European Union member states

(the chart uses the data in the World Data Base of Happiness).

A similar situation is presented by the Map of Happiness[2], drawn according to the statistics centralised in the ASEP/JDS database, by the Happiness Map[3] made by the researchers at Gallup World Poll, or by the World Bank Life in Transition Survey[4]. Even though there are significant differences between the ex-communist countries, even though the difference between the mean value of happiness for the seventeen Western countries and the mean value of happiness for the ten former communist countries of the EU seems to decrease as the democratic system and the market economy gain strength[5], the conclusion remains the same: the Iron Curtain of the Cod Ward era seems to have been replaced in the post-communist era by a genuine „iron curtain of unhappiness“[6].

A number of researchers have pointed out the connection between the level of (un)happiness in the former communist states and the various aspects of transition such as the impact of market economy[7], unemployment and the uncertainty of the labour market[8], income inequality[9], the role of social trust[10], the depreciation of human capital, deterioration of public goods, and income volatility[11] or have reached conclusions that partially invalidate the Easterlin „paradox“[12], which is similar to the old adage, „money cannot buy happiness“; comparing the correlations between GDP per capita and Life satisfaction score, calculated for the ten ex-communist states currently in the EU, in two different periods, 1999 and 2008, Rodríguez-Pose and Maslauskaite find that „while GDP per head still generates happiness in EU10, its impact seems to be waning. This may signal that the threshold at which happiness stops following GDP may be approaching“[13].

From the perspective of this paper, two remarks, made by Inglehart and Klingemann in the extensive study Gender, Culture, Democracy and Happiness are essential: „Virtually all societies that experienced communist rule show relatively low levels of subjective well-being, even when compared with societies at much lower economic level, such as India, Bangladesh, and Nigeria. Those societies that experienced communist rule for a relatively long time show lower levels than those that experienced it only since World War II“[14]. To the explanations offered by Inglehart and Klingemann in order to underline the correlation between happiness and the cultural and historical characteristics of each country, together with the possible connections with economic and democratic performance, we could add, in the case of former communist countries, a more profound analysis of the way in which the communist totalitarian system influenced people’s way of thinking, feeling and behaving, and, last but not least, the way they perceive happiness.

2. Happiness as „subjective wellbeing”

Ruut Veenhoven[15] defines happiness as „the degree to which an individual judges the overall quality of his life-as-a-whole favourably“. In order to clarify the definition, Veenhoven[16] proposed the model of the „four kinds of satisfaction“ (Figure 2). Thus, pleasure is viewed as a passing happiness, as a pleasant experience at a given moment, but it cannot be assimilated to happiness. Part-satisfaction is the enduring satisfaction generated by a certain domain of life (career, marriage etc.). Peak experience is an ecstatic moment, an experience of unique intensity or one that occurs very rarely in life. Life-satisfaction is the feeling of fulfilment, of general and lasting satisfaction generated by the evaluation of an individual entire life. This type of satisfaction is „happiness“ or „subjective wellbeing“[17].

Table 2: The four kinds of satisfaction

|

Passing |

Enduring |

|

|

Part of life |

Pleasure |

Part-satisfaction |

|

Life-as-a-whole |

Peak-experience |

Life-satisfaction (happiness) |

Source: R. Veenhoven, „How do we assess how happy we are?“, 2009

The definition of happiness given by Veenhoven combines the affective component (pertaining to the human nature in general and to each individual’s personality, in particular) with the cognitive component (pertaining to the culture the individual lives in, to its values and norms, to the way in which the individual relates to the other members of society). A few considerations from the perspective of human ethology are useful for understanding better the complexity of the human mental life and implicitly the circumstances in which humans can reach a state of happiness.

3. Human nature and cultural evolution

The „feral state“ and the „cultural moulding“[18]

From en evolutionary point of view, the human being is completely different from all other animal species. Whereas for all other beings the information that characterises the species is encoded in the genome and transmitted from one generation to the next preponderantly in a genetic manner (and only some skills are acquired by the individuals throughout their life, such as hunting for predatory animals), in the case of humans, the information that characterises the behaviour of the species is encoded in the brain and is transmitted from one generation to the next in a preponderantly cultural manner. Cultural evolution, in the case of the human species, replaces to a great extent the biological one, becoming thus a new and unique evolutionary principle[19].

A hypothesis can therefore be formulated, stating that, in the case of the human species, the specific behaviour for each particular individual has two defining dimensions: the feral state[20] and the cultural moulding[21]. The feral state is the native state of the human being, represented by genotype, manifested in terms of behaviour as the satisfaction of primary needs that are characteristic of all superior animals: hunger, thirst, „fight-or-flight“ defence, mating, minimum shelter. Cultural moulding is the one that shapes the individual’s behaviour as a defining trait of the human species and is the exclusive attribute of this species. Due to cultural moulding, the evolution of the human species has been much faster (exponential even, after the invention of writing) compared to the evolution of all other species, because the information transmitted culturally from one generation to the next is constantly modified, selected, processed and enriched. But the information can also be manipulated, depending on the human phenotype that is required at a given time in history by various would-be all-powerful Creators.

Communication and information control

In the case of the human species, the acquisition of language has allowed the development of communication at a level that was unprecedented in the animal world. Communication is the main vector of cultural moulding. As a consequence, the control of communication channels is essential in order to guide cultural moulding in the direction desired by the history „puppet masters“. Control over communication channels and information control in general have maximum effectiveness when the individual or the group of individuals are made impermeable to any information coming from the exterior that has not been filtered and delivered by the single, official communication channel. The main basis of brainwashing is the insulation of individuals from any external influence: „every bit of factual information that leaks through the iron curtain, set up against the ever-threatening flood of reality from the other, nontotalitarian side, is a greater menace to totalitarian domination than counterpropaganda has been to totalitarian movements“[22].

Always something different, always more

Unlike all other species of superior animals, which only have primary needs, pertaining to the survival of the individual in particular and to the perpetuation of the species in general, man’s needs have a hierarchical structure, similar to the structure of a pyramid, according to Maslow[23]. As certain needs are satisfied, man is no longer concerned with them, but instead goes on to satisfy needs of a higher level. Man always desires something else, always more, unlike the rest of superior animals, who satisfy their needs one at a time and without excesses. People are more easily controlled in a society in which the satisfaction of primary needs is a problem. When minor gratifications are obtained after long struggles, they can produce an intense state of satisfaction. Obtaining a bicycle in communist Albania or a colour television set in communist Romania, after years of unending waiting lists, would produce a satisfaction that was probably more intense and more enduring than earning a million dollars on Wall Street.

The society type also determines the prevalence of certain needs over others at the same hierarchical level. In societies based on private ownership, with great social inequality, the greatest part of the disfavoured masses wishes for an egalitarian system. In egalitarian societies, based on common ownership, where each works according to capacity but is rewarded according to needs, there is still discontent, as even Aristotle noted: „those who labour hard and have but a small proportion of the produce, will certainly complain of those who take a large share of it and do but little for that“[24]. If those who are unhappy with inequalities wish for an egalitarian society, while those unhappy with egalitarianism wish for a libertarian society, what could be the wishes of those living in transition and unhappy about the experience of both systems?

Times of peace and times of war

The configuration of human needs undergoes substantial changes in times of war compared to times of peace. In war times, the needs that pertain to the desire to survive come first and they result in the cancellation of innate taboos, including of the most powerful one, „thou shalt not kill“. Due to pseudospeciation[25], the enemies are viewed as lacking humanity and therefore fair game for killing. During war the rules that operate are different from those that operate in times of peace: command is centralised, orders are to be executed, not discussed, all state institutions are subordinated to the military rule, deserters are eliminated and loyalty to commanders and sacrifice in the name of the „final victory“ are fundamental values.

Military-type totalitarian rule causes the individual to be depersonalised, to repress any thoughts, feelings or behaviours that would distract his attention from his „combat mission“, to meld into the greater mass of „soldiers loyal to the party“. Hannah Arendt suggestively summarises the impact of totalitarianism on the human condition: „Totalitarian movements are mass organizations of atomized, isolated individuals. Compared with all other parties and movements, their most conspicuous external characteristic is their demand for total, unrestricted, unconditional, and unalterable loyalty of the individual member (…) Such loyalty can be expected only from the completely isolated human being who, without any other social ties to family, friends, comrades, or even mere acquaintances, derives his sense of having a place in the world only from his belonging to a movement, his membership in the party. Total loyally is possible only when fidelity is emptied of all concrete content, from which changes of mind might naturally arise.“[26] Making the state of war permanent by constantly inventing new „enemies of the people“ is vital for the existence of totalitarian regimes. Nazism reached its extreme limits during the war, while communism was established through a revolution grafted on a state if war, operated on the principle of the „permanent revolution“ and nearly outlasted the Cold War. The end of the Cold War marked the collapse of the totalitarian communist system in Europe.

4. The communist legacy

The ultimate purpose of the leaders of a totalitarian system is not to rule their subjects through terror, but instead to make them genuinely believe in the ideology they preach. Especially that the ideology of the systems experienced by European countries was painstakingly grounded in „science“, and in the places where scientific argument might have reached a quagmire, the „higher reasons of party and state“ were invoked, and these reasons were inaccessible to the ordinary citizen, who did not need to think, but only to have blind faith in the infallibility of the supreme leaders. The societal projects of totalitarian leaders were the same as grandiose: „supermen“ would build and populate the „thousand-year Reich“ and the „new men“ would build „the best of worlds“, „mankind’s golden dream“ – communism. What was achieved was in fact a different reality, as points out the Final Report of the Tismăneanu Committee: „a new form of slavery, which included, apart from control over the economic, political and social life, the mental conditioning of the subjects of the totalitarian state. In the communist totalitarian system, the party was the one that defined both what was allowed and what was forbidden. (...). Including the people’s obligation to be happy despite the degrading conditions they were condemned by the system to live in“[27]. Whereas Nazism had a short historical existence, around 12 years, and its effects on the collective consciousness were easier to combat, chiefly due to a real de-nazification process, communism lasted for much longer, almost seven decades in the Soviet space and over four decades in the European countries that had entered Moscow’s sphere of influence after World War II, and its effects of the collective consciousness have been much stronger and longer lasting.

The process of „cultural moulding“ devised by the communist leaders targeted all citizens, from the most tender age, and covered absolutely all the spheres of culture, be it material or ideatic. Impermeability to any kind of influences that were foreign to the communist ideology was to be achieved partly through the establishment of the impenetrable Iron Curtain, so that the only information source would be the official one, and partly through the rewriting of history, though the systematic restructuring of the education system[28], the aim being to sever all connections to the past, according to Orwell’s principle: „Who controls the past controls the future; who controls the present controls the past“.

Total censorship and massive propaganda, the redefinition of the entire system of norms and values, egalitarianism imposed on all planes, from the abolition of private ownership to the control of clothing and of hairdo (men wearing long hair and beards would be picked up from the street by the Militia, because they looked like some „degenerate elements of rotting capitalism“) have produced fundamental mutations in the way most citizens thought, felt and behaved. Cognitive dissonance perfected the process in the direction desired by the communists, and wherever that didn’t work, bullets took care of business. Mass murder at the time the communist system was being established – at global level there were downs of millions of victims – did not have as its ultimate purpose the enforcement of power through terror, but instead aimed to fulfil two other main goals:

1. the elimination of those who could not be „converted“, because there was a huge risk that they would operate as residual elements of another mentality, of another type of culture, possibly capable of generating currents of opinion and movements that would go against the communist ideology;

2. the constant identification of „enemies of the people“, a task that justified the perpetual state of war, that is the „permanent revolution“.

After the blood-drenched period of forced communisation, when the cultural moulding process was starting to bear fruit, and increasingly larger masses of citizens genuinely believed in the „bright future“, the party and the supreme leaders, terror remained a general but diffuse presence, mostly at psychological level, also due to the fact that it was gradually replaced by the reflex of self-censorship, of mistrust in one’s peers, of isolation, of lack of reaction for any aspects that were incomprehensible or abusive.

In general, the process of creating the „new man“ had several major effects, detectable in all former communist states:

1. The „infantilisation“ of society[29]. Like small children, the citizens had become accustomed to being obedient while expecting gratifications granted by „the grown-ups“, to reason superficially because the important decisions in life are made by „the grown-ups“, who are always right, and to accept constant, Big Brother type surveillance in their lives.

2. Demotivation. The abolition of private ownership and the system of wealth distribution according to the principle „from each according to capacity, to each according to needs“, resulted in the bitterly ironic adages „we pretend to work, they pretend to pay us“ and „those who work from dawn till night will have everything they want, those who sleep instead of working won’t be lacking anything“. As a rule, any private initiative was a priori dubious; even when it followed the lines of the communist ideology; it was suspicious that it had emerged outside the perfectly controlled and pre-programmed institutional framework.

3. Destruction of the feeling of social communion. The constant suspicion that one’s closest friend could be an informer of the political police (which was actually true in countless cases), caused the citizens to retreat in their family „shell“, to restrict to a formal level their relationships with friends, co-workers, acquaintances, in order to avoid any „unpleasant surprises“. However, suspicion was present even within families, manifested especially in the concern that children might overhear and then tell others what is being said at home, especially that communist propaganda pictured 13-year-old Pavlik Moruzov, the boy who turned his father over to the political police and then got killed by his own family, as a hero[30].

4. The depersonalisation of the individual and the atomisation of society. Anonymity was safer than the expression of opinions, or of differences of any kind. The depersonalisation of individuals and the atomisation of society were pursued programmatically through society-wide actions, starting from the dismantling of elites through the mass executions and imprisonments in the early years of communism, and up to the destructuring of families and of traditional communities, at first trough mass deportations, then through forced industrialisation, a process that required the massive and random reallocation of the rural population in the newly-built working-class districts – grey conglomerates of standard apartment blocks, with small rooms and thin walls. In parallel, a process of oversocialisation took place, in order to instil the conviction that the individual did not matter, what mattered were the „collectives of labourers“, whose single goal was to fulfil the party programme. Any personal initiative could be classified straight away as a manifestation of „individualism“, which was a reprehensible and punishable behaviour.

5. Duplicity. The world pictured by the communist propaganda in accordance with the concept of „socialist realism“ and the realities of daily life were just two different faces of the same coin. Inevitably, „[t]his double standard of truth – a conflict between official ideology and reality – led to a system of double morality. The version of truth enforced by the regime was practiced in public, at work, and at school; the other was visible only in the private sphere of life“[31].

6. Aversion to laws and authorities. The oppressive character of the communist regime, the discretionary, selective enforcement of laws according to the individual’s social position and especially to his relationship with the authorities, the system of „double morality“, generated an instinctive aversion to laws and authorities, summarised in the frustrating verdict that „laws are for fools“.

7. Using „short circuits“ in order to obtain advantages. Hard work, outstanding professional and intellectual capacity, honesty and fairness had the status of fundamental values for the „new man“, but they were appreciated and glorified only in propaganda speeches; at times the „model workers“ and „norm breakers“ were given medals and held up as an example for their collective of co-workers. In actual fact, the great advantages, such as short-circuiting the unending waiting lists for the assignment of housing, for buying cars or TV sets, the privileged supply of food and consumer goods using „home delivery agencies“ reserved for the „red bourgeoisie“, the rapid advancement of one’s career, and even the much-coveted assignment of an exclusivist „protocol house“ depended on the one hand on the manifest expression of attachment to party politics, on the enthusiastic participation in political and ideological actions, on one’s ascension through the ranks of the „driving belts“ (children and youth organisations, trade unions etc.) or directly through the party ranks to the upper echelons of the nomenklatura, on the effective collaboration with the political police, and, on the other hand, on the extent of one’s connections with influential officials or with high-ranking party executives, on the favours done for them, or even on one’s family ties to such persons – be they biological or acquired through marriage or affinity.

8. The internalisation of fraud and corruption. Aversion to laws and authorities, together with the use of „short circuits“, were the main structures of opportunity for the internalisation of frauds committed against the common property and for the vast networks of corruption. Small, but repeated theft from the output of state-owned businesses (farming, food processing, consumer goods etc.) had become a widespread factors; the perpetrators considered themselves entitled to „top up their income“, especially that ownership of the assets was held jointly and therefore they were their property as well, while the others, who worked in factories or institutions where there was nothing to steal, or from where they could not steal anything, looked acquiescently upon this practice because thus they could benefit, in their turn, from buying goods at prices that were much lower than the official ones. Even in the army, whenever a conscript noticed that a component of his gear was missing he considered himself entitled to steal that component form another soldier, and the commanding officers turned a blind eye to this sort of acts, because they did not view them as theft, but instead as „restocking“ the equipment. On the other hand, the growing shortage of food and of consumer goods caused the general spread of „blat“, defined by Alena Ledeneva[32] as „the use of personal networks and informal contacts to obtain goods and services in short supply and to find a way around formal procedures“. The „blat“, using one’s connections to the highest institutional or party levels, including (but not necessarily) the payment of bribes in order to obtain advantages were not perceived as crimes, but instead as practices that were crucial to the improvement of personal and family life under the circumstances of a rigid and oppressive system. Similarly, offering „thoughtful gifts“ consisting of money, services or products to doctors or to various public officers in exchange for their services had come to be considered a „fitting“ and „common sense“ practice. In Romania, but not only, the pack of Kent cigarettes (or the 200 pack, depending on the size of the problem) had become the most common and elegant form of „compensating“ for the services received form officials. The „gift“, however, would grow according to the value of services. Last but not least, huge smuggling networks developed in order to supply the population with Western merchandise, in particular with cigarettes, whisky, blue jeans, video recorders and videotapes (bearing in mind that in Romania, for instance, the public television’s schedule had been reduced in the ‘80s to two hours per evening, the entire programming being dedicated to Nicolae Ceaușescu’s cult of personality), but also with cosmetics, foodstuffs etc.; the „importers“ were the few citizens who had the right to cross through the Iron Curtain (staff working on ships, planes, international trains, foreign students, contractors who worked abroad, and even a few members of the nomenklatura or of the political police).

9. Reaching the utopia. Apart from all the frustrations generated by life in a closed, grey, oppressive system, the communist propaganda had its own powerful and lasting effects on the collective consciousness. The restructuring of the education system according to the communist ideology, the mandatory classes of „political education“ taught in absolutely all institutions, at all levels, the redefinition of the entire culture around „socialist realism“, the censorship that eliminated all information concerning the more sordid aspects of life in a communist system, allowing only the glorification of leaders and the presentation of the „great accomplishments“ on the road to „mankind’s bright future“ have inoculated in the larger categories of population the latent belief that a society such as the one described by the political education handbooks was truly possible. From a psychological point of view, there could be an explanation: the belief in a just world[33] was projected into the future in order to solve thus the strong internal discomfort generated by the cognitive dissonance caused by the antagonism between the „fabricated world“ and the real one. The „scapegoat“ was some times imperialism, other times the „hostile elements“ that did everything in their power to stop the construction of „the best of worlds“, as the communist propaganda asserted, and yet other times the totalitarian leaders who were unable to put into practice those „noble ideals“, as many citizens genuinely believed, of course without stating this belief out loud. It is not by accident that many who suffer from nostalgia in post-communist countries, when their opinion about communism is asked during polls say that it was „a good idea, applied wrongly“. Moreover, certain aspects of the communist society – the provision of a home and of a job for every (able-bodied) citizen, the egalitarian spirit, reflected in a payroll system based on position rather than on the individual, the elimination of discrimination (even though it still existed, censorship made sure it was not discussed, the way there was no discussion about crime rates, abandoned children, AIDS sufferers etc. – and what was not discussed did not exist), the predictability of life, grey as it was etc. made the nostalgists think that „a just world“, where everyone gets what they deserve, can exist.

5. The shock of transition

The collapse of the communist system offered the citizens in these countries the freedom they had so long dreamed about. But in the early days of the construction of the new democratic system on the ruins of totalitarianism, freedom was not understood and exercised in its democratic sense, that is within legal limits, as Montesquieu explained: „It is true that in democracies the people seem to act as they please; but political liberty does not consist in an unlimited freedom. (…) Liberty is a right of doing whatever the laws permit“[34]. The old laws, still applicable, were disregarded and even manifestly breached, because they were viewed as belonging to the „communist legacy“, and new laws had not been issued yet. On the backdrop of this „legislation vacuum“, a state of chaos began to reign, with great profits to be made my individuals without scruples: „society has freed itself, true, but in some ways it behaves worse than when it was in chains. Criminality has grown rapidly, and the familiar sewage that in times of historical reversal always wells up from the nether regions of the collective psyche has overflowed into the mass media, especially the gutter press. But there are other, more serious and dangerous, symptoms: hatred among nationalities, suspicion, racism, even signs of fascism; vicious demagogy, intrigue, and deliberate lying; politicking, an unrestrained, unheeding struggle for purely particular interests, a hunger for power, unadulterated ambition, fanaticism of every imaginable kind; new and unprecedented varieties of robbery, the rise of different mafias; the general lack of tolerance, understanding, taste, moderation, reason.“[35]

Those who profited from this state of chaos were mainly former high-ranking communist dignitaries and superior officers of the political police, because they were the ones that had the monopoly of information and could use the former organisational structures and their own connections, both inside the country and abroad, capable of helping them exploit the „legislation vacuum“ and to manipulate the population for their own interest. Their ranks were soon joined by individuals from the crime world, accustomed to lawbreaking and to corrupt practices. The two categories – the „exes“ and the criminals – soon were in a position to make „the rules of the game“ in the new society „with a democratic face“. The explanation for their rise is similar to that given by Hayek for the rise of totalitarian leaders, in a different, but the same as murky historical context. In the chapter „Why the Worst Get on Top“ of The road to Serfdom[36], Hayek notes that the access to power is very quick for individual lacking scruples and inhibitions, because they do not have the moral dilemmas that would stop others from using any means available in order to satisfy their interests, including, or particularly the means that are contrary to the interests of their peers and of the common good.

The premeditated perpetuation of the „legislation vacuum“ allowed the structures coordinated by former members of the nomenklatura and by officers of the political police to accumulate increasingly more economic power, especially though the process of privatising according to their own interests of the former collectivist economy and through massive fraud perpetrated against public finances, as well as to acquire political power by controlling and manipulating the political scene. The new society, in which fraud, corruption and imposture were becoming the rule rather then the exception, was far from the albeit idealised „democratic“ model desired by most citizens. Frustration returned, generating a dramatic „post-communist syndrome“, manifested in „learned helplessness“, „specific immorality“ and „lack of civic virtues“[37].

From a psycho-sociological perspective, both the enthusiastic anticommunist manifestations of 1989 and the unfortunate „post-communist syndrome“ of the following years and even decades can also be explained through the relative deprivation theory. Ted Gurr defines relative deprivation as „the actors’ perception of discrepancy between their value expectations and their value capabilities. Value expectations are the goods and conditions of life, to which people believe they are rightfully entitled. Value capabilities are the goods and conditions they think they are capable of getting and keeping.“ [38]

During communist regimes, the information that seeped through the Iron Curtain about the realities of Western democracies, which were totally different from what the communist propaganda described, generated in the collective consciousness expectations regarding the living standards people believed were entitled to have. We must note that such expectations had a certain dose of idealism, on the one hand due to the projection of the ideal society preached by the communist ideology (especially in terms of „social justice“) towards the model of a democratic society, given that the standards of living were perceived as indisputably higher than in a communist society, where the social climate was worsening inexorably, and on the other hand due to an instinctive rejection of the totalitarian propaganda, which had crossed the persuadability threshold, producing the opposite of the effects pursued by the system leaders; thus, increasingly more citizens believed that the official information focussing exclusively on the „dark side“ of capitalism (inequality, unemployment, greed, drug trafficking, organised crime etc.) were lies or exaggerations, and gave greater credit to its „bright side“: a society in which „everyone gets what they deserve“, where average people live in beautiful residential district and where, despite all difficulties, the „good guys“ always win – as all American movies trafficked through the Iron Curtain clearly showed. The events of 1989 then generated the second condition of relative deprivation: the citizens of the entire „socialist bloc“ became aware not only that they deserved a better life, but also that they were capable of obtaining it. The frustration generated by the experience of relative deprivation fired up the anticommunist movements in Central and Eastern Europe, causing, one by one, the collapse of communist regimes, and reaching as far as Moscow.

During the transition period, the manifestation of the two circumstances that define relative deprivation is debatable. After the traumatising experience of communist times and the chaotic reality of a growing democracy, the many that are frustrated are no longer sure that the life they believe they deserve and that they are capable of obtaining can really exist. Here we have two essential notes made by Inglehart and Klingemann’s study:

1. the peoples of the former communist countries are unhappier than those with a much lower economic level; and

2. the overall level of unhappiness is higher in the peoples that have experienced communism for almost seven decades, compared to that of peoples who experienced it for four decades. In general, metaphorically speaking, those made miserable by the transition are somewhere in a no man’s land between two real worlds (the totalitarian and the democratic one), and an imaginary one (the utopian world created in their minds during decades of communist propaganda). In other words, forcing a paraphrase of great philosophical ideas, after spending decades chained up in the dark cave of totalitarianism, on the walls of which were projected the shadows of „the best of the worlds“, they broke their chains and rushed outside, where, blinded by sunlight, they started a war waged by everyone against everyone.

The differences between one former communist country and another are major, and so seem to be the differences between their destinies after more than two decades since the fall of the totalitarian system. However, three large categories can be identified:

1. States that used to be part of the Soviet Union and have experienced the communist system for approximately seven decades. These states have no democratic tradition to speak of, as they transitioned straight from an autocratic system to a totalitarian one. In this space, the „communist legacy“ is deeply ingrained, and the construction of the democratic system has translated into the rapid monopolisation of economic and political power by the „red“ oligarchs coming from the former nomenklatura and from the former political police or having very close ties with these structures. The population’s frustrations cannot speed up the process of real democratisation in the country, because the system of the „red“ oligarchy is much too strong, and the democratic culture is much too weak. As a result, the system in operation is a hybrid one, a so-called „guided democracy“, which combines the formal implementation of democratic norms and liberties, while the power is in fact concentrated in the hands of a „papa dear“. The real democratisation of these countries is a complex and lengthy process. Its success will depend on the dynamics of the crystallisation and spread of democratic culture, but also on the access to the top decision-making level of visionary, competent individuals who espouse democratic values and are capable of setting this process on an irreversible course.

2. Some states in Central and Eastern Europe that have experienced communism for four decades, but where the communisation process has not been fully completed. Here, the democratic pre-communist traditions, religion, the cultural connections with the space outside the Iron Curtain have survived to a significant extent throughout the communist regimes. In these countries, the „communist legacy“ has not become ossified, and the dual process of transition towards democracy and the market economy has started on an irreversible path, even though the bouts of nostalgia sometimes reach considerable proportions. As a rule, however, nostalgia is manifested in a democratic framework, sometimes in the wide support given to left-wing or populist forces, but this also happens in established democracies going through difficult periods, without reaching the point where the legitimacy democratic system is challenged. A brief comparative overview shows that the level of happiness in these countries is higher than in all the other countries that used to belong to the former Soviet-influenced space, and close to the median of Western democracies.

3. Some states in Central and Eastern Europe that have experienced four decades of communist regime, but where the communisation process has been as tough as the one carried out in the former Soviet space. In these countries, among them two European Union members – Romania and Bulgaria –, as well as aspiring or future aspiring members – Albania, Moldova etc.), unhappiness is accompanied by a gloomy feeling of hopelessness. The communist experience has been suffocating, democracy appears to be chaotic, and the performance of the new political elite, with major integrity issues and lacking political vision, is deplorable. The incoherent, tangled and unstable legal system, endemic corruption, precarious infrastructure and the absence of country strategies increase the reluctance of major international players about investing in the country, powerful groups specialised in defrauding the public budget hinder the materialisation of innovative initiatives, and the members of the most dynamic segment of the active population have chosen to leave the country in droves, heading West. The disappearance in a relatively short period of time of millions of individuals from the taxable population, corroborated with mass tax evasion, with huge fraud in public finances and with the lack of appetence for the absorption of European funds, have all but demolished the pension and welfare system, the health system, the education system and in general all public institutions, which face chronic underfunding. However, although the civil society is extremely feeble, the pre-communist democratic tradition and the increasingly stronger connections with Western democracies have helped the development of a latent democratic culture, which is strong enough not to erode the legitimacy of the democratic system. A way out of this vicious circle of poverty, corruption and imposture is possible through the coagulation of a concerted, genuine and competent political will at the top of political decision-making. In this respect, accelerating the implementation of the community acquis for the EU member states and accelerating the process of European integration of aspiring countries, as well as empowering the most important decision-makers in the honest, pragmatic and rapid application of the „roadmap“ are vital for breaking this vicious circle.

6. Instead of conclusions: „democratic happiness“

In former communist states, ascertaining the general level of happiness as „the degree to which an individual judges the overall quality of his life-as-a-whole favourably“ is difficult, as most citizens have to calculate an average between the experiences they have had in two completely different systems, to which they have to add the mental remanence of the ideal model of society inoculated by the communist propaganda. Moreover, the data are rare, and they have been obtained according to different methodologies, fact that makes the performance of a comparative study even more difficult. The multi-disciplinary and systematic approach of the issue of happiness in this space is a research path that needs to be consolidated, because it can yield crucial information for adapting successful transition models to the cultural specificities of each people. Because the successful journey through transition from totalitarianism to democracy increases, in its turn, the general level of happiness. Drawing a parallel with the theory of „democratic peace“, we could propose the hypothesis of the „democratic happiness“: at least for the ex-communist countries in transition, so far the only tried and tested way for increasing the general level of happiness is the consolidation of the democratic system.

References

Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (New York: Meridian, 1958)

Richard Easterlin, „Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence“, in Nations and Households in Economic Growth: Essays in Honour of Moses Abramowitz, ed. P.A. David and M.W. Reder, 89-125 (New York and London: Academic Press, 1974)

Irenäus Eibl-Eibesfeldt, Krieg und Frieden aus der Sicht der Verhaltensforschung (München: Piper, 1975)

Bogdan Ficeac, Cenzura comunistă și formarea „omului nou“ [Communist Censorship and the Shaping of the „New Man“] (Bucharest: Nemira, 1999)

Bogdan Ficeac, De ce se ucid oamenii [Why men kill men] (București:RAO, 2011)

Ted Robert Gurr, Why men rebel (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1970)

Friedrich Hayek, The Road to Serfdom (London and New York: Routledge Classics, 2005)

Ronald Inglehart and Hans-Dieter Klingemann, „Genes, culture, democracy, and happiness“, in Culture and subjective well-being, ed. E. Diener and E.M.Suh, 171 (Cambridge, MA, US: The MIT Press, 2000).

Alena Ledeneva, Russia’s Economy of Favors: Blat, Networking and Informal Exchange (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998)

Abraham Maslow, Motivation and personality (New York, NY: Harper, 1954)

Charles de Secondat Baron de Montesquieu, The Spirit of the Laws (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989)

Ruut Veenhoven, Conditions of happiness, (Dordrecht, Netherlands: Reidel Publishing Company, 1984)

Ruut Veenhoven, „How do we assess how happy we are?“, in Happiness, Economics and Politics: Towards a multi-disciplinary approach, ed. A. K. Dutt and B. Radcliff, Chapter 3, 45-69 (Cheltenham UK: Edward Elger Publishers, 2009)

Stefano Bartolini, Malgorzata Micucka and Francesco Sarracino, „Money, Trust and Happiness in Transition Countries: Evidence from Time Series“ (Working Paper No. 2012-4, Luxembourg: CEPS/INSTEAD, 2012)

David G. Blanchflower, „Unemployment, Well-Being, and Wage Curves in Eastern and Central Europe“,, Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, vol. 15(2001): 364-402

Carola Grün and Stephan Klasen, „Has transition improved well-being? An analysis based on income, inequality-adjusted income, nonincome, and subjective well-being measures“ (Working Papers 04, Cape Town: Economic Research Southern Africa, 2005)

Serghei Guriev and Ekatetrina Zhuravskaya, „(Un)Happiness in Transition“, Journal of Economic Perspectives 23 (2009): 143–68.

Bernd Hayo, „Micro and macro determinants of public support for market reforms in Eastern Europe“ (ZEI Working Papers B 25, Center for European Integration Studies, University of Bonn, 1999), http://econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/39572/1/309765331.pdf, (accessed 30 May, 2013)

Bernd Hayo and Wolfgang Seifert, W. (2003). „Subjective economic well-being in Eastern Europe“, Journal of Economic Psychology, vol. 24(2003): 329-348.

Melvin Lerner and Dale Miller, Just world research and the attribution process: Looking back and ahead. Psychological Bulletin, 85 (1978), 1030-1051.

Orsolya Lelkes, „Tasting freedom: Happiness, religion and economic transition“, Journal of EconomicBehavior & Organization, 59 (2006):173–194

Andrés Rodriguez-Pose and Kristina Maslauskaitec, „Can policy make us happier? Individual characteristics, socio-economic factors and life satisfaction in Central Eastern Europe“, Bruges European Economic Research Papers 22 (2011): 20

Aristotles, Politics: A Treatise on Government, Book II, Chapter V, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/6762/6762-h/6762-h.htm) (accessed: 5 June,.2013)

Comisia Prezidențială pentru Analiza Dictaturii Comuniste din România, Raport Final [Final Report], 2006, http://www.corneliu-coposu.ro/u/m/raport_final_cadcr.pdf (accessed 4 June, 2013)

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, „Life in Transition Survey II“, Cap. 2: Attitudes and Values, 2013, http://www.ebrd.com/downloads/research/surveys/LiTS2ec.pdf, (accessed 30 May, 2013)

Vaclav Havel, „Paradise lost“, The New York Review of Books, 9 April, 1992, http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/1992/apr/09/paradise-lost/?pagination=false (accessed 4 June, 2013)

Martina Klicperová-Baker, Post-Communist Syndrome, Open Society Institute Research Support Scheme, 1999, 2, http://rss.archives.ceu.hu/archive/00001062/01/62.pdf (accessed 4 June, 2013)

Jaime Diez Medrano, „Map of Happiness“, Banco de datos ASEP/JDS , 2013, http://www.jdsurvey.net/jds/jdsurveyMaps.jsp?Idioma=I&SeccionTexto=0404&NOID=103, (accessed 30 May, 2013)

TargetMap Directory. (2010). World map of happiness. Map by Country. Retrieved May 5, 2013 from http://www.targetmap.com/viewer.aspx?reportId=2903

Ruut Veenhoven, „Happiness in Nations“, World Database of Happiness (Rotterdam: Erasmus University, 2013), http://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl (accessed 30 May, 2013).

NOTE

[1] Ruut Veenhoven, „Happiness in Nations“, World Database of Happiness (Rotterdam: Erasmus University, 2013), http://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl (accessed 30 May, 2013).

[2] Jaime Diez Medrano, „Map of Happiness“, Banco de datos ASEP/JDS , 2013, http://www.jdsurvey.net/jds/jdsurveyMaps.jsp?Idioma=I&SeccionTexto=0404&NOID=103, (accessed 30 May, 2013)

[3]http://www.targetmap.com/viewer.aspx?reportId=2903 (accessed 30 May, 2013)

[4] European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, „Life in Transition Survey II“, Cap. 2: Attitudes and Values, 2013, http://www.ebrd.com/downloads/research/surveys/LiTS2ec.pdf, (accessed 30 May, 2013)

[5]idem, 21

[6] Orsolya Lelkes, „Tasting freedom: Happiness, religion and economic transition“, Journal of EconomicBehavior & Organization, 59 (2006):173–194

[7] Bernd Hayo, „Micro and macro determinants of public support for market reforms in Eastern Europe“ (ZEI Working Papers B 25, Center for European Integration Studies, University of Bonn, 1999), http://econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/39572/1/309765331.pdf, (accessed 30 May, 2013); Bernd Hayo and Wolfgang Seifert, W. (2003). „Subjective economic well-being in Eastern Europe“, Journal of Economic Psychology, vol. 24(2003): 329-348.

[8] David G. Blanchflower, „Unemployment, Well-Being, and Wage Curves in Eastern and Central Europe“,, Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, vol. 15(2001): 364-402

[9] Carola Grün and Stephan Klasen, „Has transition improved well-being? An analysis based on income, inequality-adjusted income, nonincome, and subjective well-being measures“ (Working Papers 04, Cape Town: Economic Research Southern Africa, 2005)

[10] Stefano Bartolini, Malgorzata Micucka and Francesco Sarracino, „Money, Trust and Happiness in Transition Countries: Evidence from Time Series“ (Working Paper No. 2012-4, Luxembourg: CEPS/INSTEAD, 2012)

[11] Serghei Guriev and Ekatetrina Zhuravskaya, „(Un)Happiness in Transition“, Journal of Economic Perspectives 23 (2009): 143–68.

[12] Richard Easterlin, „Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence“, in Nations and Households in Economic Growth: Essays in Honour of Moses Abramowitz, ed. P.A. David and M.W. Reder, 89-125 (New York and London: Academic Press, 1974)

[13] Andrés Rodriguez-Pose and Kristina Maslauskaitec, „Can policy make us happier? Individual characteristics, socio-economic factors and life satisfaction in Central Eastern Europe“, Bruges European Economic Research Papers 22 (2011): 20

[14] Ronald Inglehart and Hans-Dieter Klingemann, „Genes, culture, democracy, and happiness“, in Culture and subjective well-being, ed. E. Diener and E.M.Suh, 171 (Cambridge, MA, US: The MIT Press, 2000).

[15] Ruut Veenhoven, Conditions of happiness, (Dordrecht, Netherlands: Reidel Publishing Company, 1984), 22-24.

[16] Ruut Veenhoven, „How do we assess how happy we are?“, in Happiness, Economics and Politics: Towards a multi-disciplinary approach, ed. A. K. Dutt and B. Radcliff, Chapter 3, 45-69 (Cheltenham UK: Edward Elger Publishers, 2009)

[17] The definition of happiness given by Veerhoven is used as a basis by the methodologies for measuring happiness values (as „subjective wellbeing“) employed by most studies performed worldwide. The two main measures are: 1. Happiness measure („Taking all things together, would you say you are very happy, quite happy, not very happy, or not at all happy?“) and 2. Life satisfaction measure („All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days?“ on a scale from 1 to 10).

[18] Bogdan Ficeac, De ce se ucid oamenii [Why men kill men] (București:RAO, 2011)

[19] Irenäus Eibl-Eibesfeldt, Krieg und Frieden aus der Sicht der Verhaltensforschung (München: Piper, 1975)

[20] Carl von Linné, talking about the rare but shocking cases of children that had grown in total isolation or in the wilderness, said that such children seem to belong to a completely different species from Homo sapiens, a species he called Homo ferus (from the Latin ferus – wild, feral).

[21] We prefer to use this term in order to extrapolate into the anthropologic-cultural plane the concept of „social learning“, used predominantly in psychology. Cultural moulding concerns both the shaping of an individual’s behaviour from the earliest age, as well as the sometimes dramatic modification of the behaviour of individuals, or the radical modification of thought, feeling and behaviour in the case of large groups of people, sometimes of entire peoples.

[22] Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (New York: Meridian, 1958), 392.

[23] Abraham Maslow, Motivation and personality (New York, NY: Harper, 1954)

[24] Aristotles, Politics: A Treatise on Government, Book II, Chapter V, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/6762/6762-h/6762-h.htm) (accessed: 5 June,.2013)

[25] The term was used for the first time by Erik Erikson, quoted by L. J. Friedman in Identity’s Architect: A Biography of Erik H. Erikson (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2000).

[26] Hannah Arendt, The Origins, of Totalitarianism, 323-324.

[27] Comisia Prezidențială pentru Analiza Dictaturii Comuniste din România, Raport Final, 2006,10, http://www.corneliu-coposu.ro/u/m/raport_final_cadcr.pdf (accessed 4 June, 2013)

[28] Even arithmetic schoolbooks were edited for ideology, cf. Bogdan Ficeac, Cenzura comunistă și formarea „omului nou“ [Communist Censorship and the Shaping of the „New Man“] (Bucharest: Nemira, 1999). For example, the problem „One poor farmer harvested 2026 kg of wheat from his land. He handed to the state the quota of 578 kg. How many kilograms of wheat were he left with?“ was expunged by the communist censors in 1950s Romania, due to the serious ideological errors that it contained: 1. The farmer could not have harvested „his land“, as private property could not exist even in memory. 2. He could not have handed the state the „quota“, as the state did not take „quotas“, but instead took over the entire farming, industrial etc. production, so that it could look after all citizens according to the principle „from which according to capacity, to each according to needs“. 3. There is no such thing as a „poor farmer“. Communism has eradicated poverty and all citizens are equal, prosperous and happy!

[29] B. Vacková, Parallelen der Pathologie der Einzelnen un der Gesellschaft. Sigmund Freud House Bulletin, 14 (1990), special issue, 36-41, cf. Martina Klicperová-Baker, Post-Communist Syndrome, Open Society Institute Research Support Scheme, 1999, 2, http://rss.archives.ceu.hu/archive/00001062/01/62.pdf (accessed 4 June, 2013)

[30] The veracity of the episode was the topic of heated controversies in post-communist times, but its propaganda effect, at the time it was used, was the highest possible.

[31] Martina Klicperová-Baker, Post-Communist Syndrome, 2.

[32] Alena Ledeneva, Russia’s Economy of Favors: Blat, Networking and Informal Exchange (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 1

[33] Melvin Lerner and Dale Miller, Just world research and the attribution process: Looking back and ahead. Psychological Bulletin, 85 (1978), 1030-1051.

[34] Charles de Secondat Baron de Montesquieu, The Spirit of the Laws (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), XI, 3

[35] Vaclav Havel, „Paradise lost“, The New York Review of Books, 9 April, 1992, http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/1992/apr/09/paradise-lost/?pagination=false (accessed 4 June, 2013)

[36] Friedrich Hayek, The Road to Serfdom (London and New York: Routledge Classics, 2005)

[37] Martina Klicperová-Baker, Post-Communist Syndrome, 6-7.

[38] Ted Robert Gurr, Why men rebel (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1970), 24.