The fight for the recognition of women’s rights arises in Spain in the last decade of the 19th century. Among the pioneers of the fight for women’s rights, we need to mention Arenal, Emilia Pardo Bazán and Rosalía de Castro, who advocated the change of women’s legal status and their right to education.

In April 1924, Miguel Primo de Rivera gave women the right to vote in municipal assemblies by approving the Municipal Statute, in 1924, even if this regulation was never enforced. The document contained certain prohibitions though: neither a married woman nor a prostitute could take part in political life[1].Various feminist organisations and associations played an important role in the fight for women’s rights.

November 19, 1933 is the date on which women acquire the right to vote in Spain.

The Second Republic recognized women’s right to be elected to Congress[2]. Article 36 of 1931 Constitution states that: “Citizens of one sex or another, aged 23, have the same electoral rights under the law.“

In the first Republican Cortes in June 1931, two women were mandated: Clara Campoamor, from the Radical Party, and Victoria Kent, from the Socialist Party. Subsequently, Margarita Nelken, from the Socialist Party, got a mandate.

Women’s situation began to change significantly only in the ‘60s and ’70s, due to substantial social, economic and cultural transformations. In 1960, the Law on Women’s Political, Professional and Labour Rights was adopted.

Since the first democratic election on 15 June 1977, feminist movements have mobilized and turned their attention towards the political parties (mainly towards left-wing political parties), and these ones, in their turn, responded, as they were interested in attracting women’s vote. Although, in the first election, only 27 women were elected, it was considered an important step in representing women in the legislative forum.

The next step in the evolution of women’s rights was the adoption of the 1978 Constitution, which, by means of its regulations, improved significantly the principle of gender equality.

Thus, article 9 paragraph 2 provided that:“It is incumbent upon the public authorities to promote conditions which ensure that the freedom and equality of individuals and of the groups to which they belong may be real and effective, to remove the obstacles which prevent or hinder their full enjoyment, and to facilitate the participation of all citizens in political, economic, cultural and social life.“

Article 14 provided in an effective manner: “Spaniards are equal before the law and may not in any way be discriminated against on account of birth, race, sex, religion, opinion or any other personal or social condition or circumstance.“

A defining moment in the battle for the recognition of women’s rights was the creation, in 1983[3], of the Institute of Women (Instituto de la Mujer)[4], a leading body in the Spanish administration, whose fundamental role was to create public policies for the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women through “Women’s Equal Opportunities Plans“[5].

The current regulatory framework governing the parliamentary elections in Spain is ruled by the Constitution, Law no.5/1985 regarding the General Electoral Regime[6](LOREG), and Organic Law no. 3/2007 concerning the effective gender equality[7].

The Cortes Generales represent the Spanish people and consist of the Congress of Deputies and the Senate.

Congress consists of a minimum of three hundred and a maximum of four hundred Deputies, elected by universal, free, equal, direct and secret suffrage, under the terms established by law. The electoral district is the province. The cities of Ceuta and Melilla shall each be represented by one Deputy. The total number of Deputies shall be distributed in accordance with the law, with each electoral district being assigned a minimum initial representation and the remainder being distributed in proportion to the population. The election in each electoral district shall be conducted on the basis of proportional representation. Congress is elected for four years. The term of office of the Deputies ends four years after their election or on the day that the House is dissolved.

All Spaniards who are entitled to the full exercise of their political rights are electors and eligible for election. The law shall recognize and the State shall facilitate the exercise of the right to vote of Spaniards who are outside Spanish territory. Elections shall take place between thirty and sixty days after the end of the previous term of office. The Congress so elected must be convened within twenty five days following the holding of elections.

The parties, federations, coalitions and political groups will designate, under LOREG’s terms, the people who will represent them within the Electoral Assembly. The candidates supported by the political parties, federations, coalitions and political groups are required to submit a declaration of acceptance of their candidature[8].

The candidatures proposed in the elections must be balanced between men and women. A LOREG’s rule establishes that at least 40% of the members on a list should be either men or women. In the elections for Legislative Assemblies of the Autonomous Communities, the laws governing the electoral matters may lay down rules to promote a better representation of women on the lists of candidates in the respective community legislative election.

Also, article 14 paragraph 4 of Law no. 3/2007 on equality between women and men provides that there should be an “equal participation of women and men in relation to the electoral candidacies and decision-making process“.

Women’s representation in the Congress of Deputies (1977- October 2019)[9]

|

Legislature |

Between |

Total seats |

Number of seats |

% |

|

Constituent Assembly |

1977-1979 |

361 |

21 |

5.81 |

|

I Legislature |

1919-1982 |

392 |

24 |

6.12 |

|

II Legislature |

1982-1986 |

390 |

23 |

5.89 |

|

III Legislature |

1986-1989 |

394 |

33 |

8.37 |

|

IV Legislature |

1989-1993 |

389 |

54 |

13.88 |

|

V Legislature |

1993-1996 |

407 |

65 |

15.97 |

|

VI Legislature |

1996-2000 |

409 |

98 |

23.96 |

|

VII Legislature |

2000-2004 |

416 |

132 |

31.73 |

|

VIII Legislature |

2004-2008 |

399 |

146 |

36.59 |

|

IX Legislature |

2008-2011 |

413 |

158 |

38.25 |

|

X Legislature |

2011-2016 |

437 |

175 |

40 |

|

XI Legislature |

2016-2016 |

351 |

139 |

39.60 |

|

XII Legislature |

2016-2019 |

350 |

144 |

41.14 |

|

XII Legislature |

2019-on going |

350 |

171 |

48.85 |

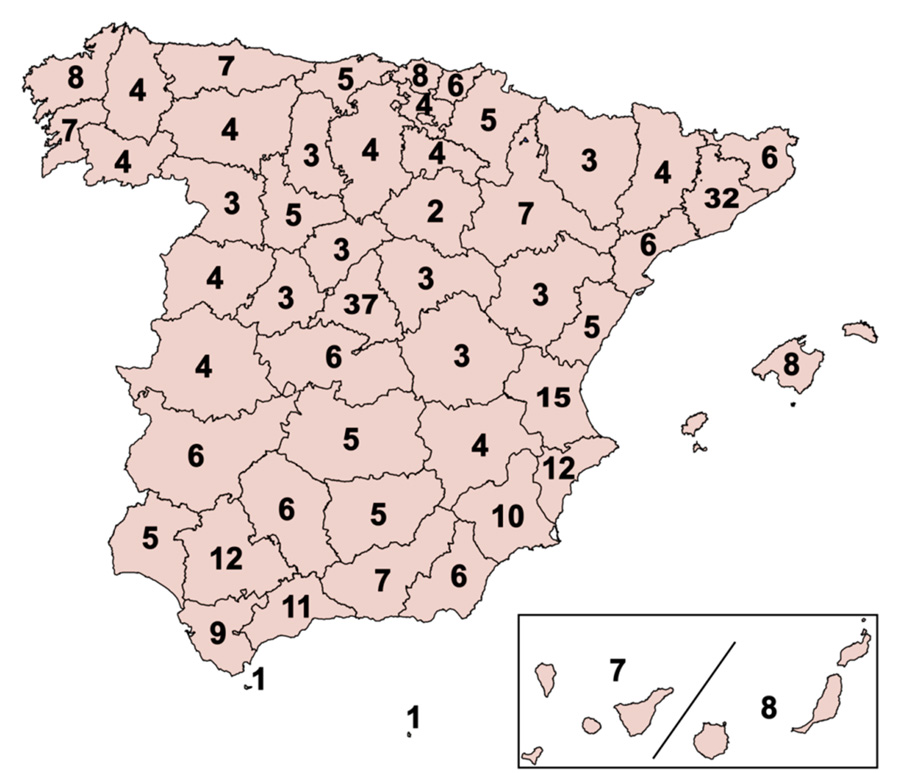

Distribution of the number of mandate for the Congress of Deputies – April 29, 2019

The Senate is the House of territorial representation.

In each province, four Senators shall be elected by the voters thereof by universal, free, equal, direct and secret suffrage, under the terms established by an organic law.

In the islands provinces, each island or group of islands with a «Cabildo» or Island Council shall constitute an electoral district for the purpose of electing Senators, of whom there shall be three for each of the larger islands –Gran Canaria, Mallorca and Tenerife– and one for each of the following islands or groups of islands: Ibiza-Formentera, Menorca, Fuerteventura, Gomera, Hierro, Lanzarote and La Palma. The cities of Ceuta and Melilla shall each elect two Senators[10].

The Autonomous Communities shall, moreover, nominate one Senator and a further Senator for each million inhabitants in their respective territories. The nomination shall be incumbent upon the Legislative Assembly or, in default thereof, upon the Autonomous Community’s highest corporate body, in accordance with the provisions of the Statutes, which shall, in any case, guarantee adequate proportional representation.

The Senate is elected for four years. The Senators’ term of office shall end four years after their election or on the day that the House is dissolved.

Two systems are used to elect the Senate members:

1. 208 senators are directly elected in the 52 plurinominal constituencies (with four senators each), through the limited vote system, in which every voter does not vote a list of candidates, but a maximum of three candidates;

2. the other senators are indirectly elected[11], namely they are appointed by the Legislative Assemblies of the Autonomous Communities, as previously mentioned. The right to submit candidatures is reserved to the following entities[12]:

a. Political parties and federations registered in the Electoral Register;

b. Alliances which establish at the time of the election;

c. Elector groups[13]. Candidatures shall be submitted between the 15th and the 21st days after convening the election. The candidature submission procedure must also meet certain formal requirements:

– submission of the candidature acceptance statement and of the documents proving the fulfillment of the eligibility criteria by each candidate;

– each candidature must clearly indicate the name, logo and symbol of the political entities, as well as the name and surname of the candidates;

– the lists of candidates must have a balanced composition between women and men[14];

– each list must include the same amount of candidates as the amount of available mandates, by mentioning the rank on the list. If the lists include also alternates, their number may not exceed 10[15];

– candidatures whose symbols reproduce the flag of Spain or have names and symbols relating to the Spanish monarchy shall not be accepted;

– a candidate can submit his candidature in a single constituency[16];

– the candidatures from elector groups must be accompanied by the list of signatures required by law in order to be able to participate in the electoral process. None of the electors can submit multiple candidatures.

The candidatures submitted will be published in the State Gazette[17].

Arend Lijphart characterizes the Spanish Senate as being “incongruent“ for three reasons:

– the continental provinces (except for the islands and the two North African enclaves) are equally represented;

– the majority of senators are elected through a semi-proportional limited system (in contrast to the RP method which is used to elect the first Chamber);

– nearly a fifth of the senators are elected by the legislatures of the autonomous regions[18].

Women’s representation in the Spanish Senate (1977-2019)[19]

|

Legislature |

Between |

Total seats |

Number of seats |

% |

|

Constituent Assembly |

1977-1979 |

206 |

6 |

2.91 |

|

I Legislature |

1979-1982 |

213 |

6 |

2.81 |

|

II Legislature |

1982-1986 |

254 |

12 |

4.72 |

|

III Legislature |

1986-1989 |

266 |

16 |

6.01 |

|

IV Legislature |

1989-1993 |

277 |

34 |

12.27 |

|

V Legislature |

1993-1996 |

256 |

37 |

14.45 |

|

VI Legislature |

1996-2000 |

258 |

43 |

16.66 |

|

VII Legislature |

2000-2004 |

258 |

75 |

29.06 |

|

VIII Legislature |

2004-2008 |

259 |

74 |

28.57 |

|

IX Legislature |

2008-2011 |

262 |

101 |

38.54 |

|

X Legislature |

2011-2016 |

265 |

123 |

46.41 |

|

XI Legislature |

2016-2016 |

265 |

104 |

39.24 |

|

XII Legislature |

2016-2019 |

266 |

97 |

36.46 |

|

XIII Legislature |

2019-on going |

265 |

103 |

38.68 |

However, the above mentioned figures do not represent a balanced composition if we take into consideration the balance between the seats held by men and women in the Spanish Senate. The reason for this imbalance is largely triggered by the electoral system of the Spanish Senate, which impedes balanced candidacies, particularly in comparison with Deputies Congress. Furthermore, the elector may distribute his three votes freely, therefore parity shall also depend on his choice.

On the other side, in the case of Senator women appointed by Independent Regional Parliaments, the requirement for proportional distribution between their Parliamentary Groups also impedes this balance since there are groups which can only appoint one candidate. Therefore, one of the genders will always go unrepresented through this manner. Moreover, the fact that certain Self-Governing Communities appoint a smaller and odd number of senators determine this imbalanced and derogatory number of female representatives.

Although important steps have been taken in Spain’s legislation and political life not only to effectively implement the principle of equal opportunities between women and men, but also in terms of a larger representation of women in the Spanish Parliament, there is always room for the improvement of these two aspects.

Therefore, with regard to women’s rights in Spain, particularly of their political rights, we can conclude that:

– the feminist movement in Spain has been the main driver of getting their rights. If the first battle was given to obtain the right to vote, today we are talking about the right to a gender parity representation (parity democracy)[20];

– women associating in different non-governmental structures, through which women can fight for their rights, has been and remains the fundamental and imprescriptible mean for the battles that were already given and for the battles to come;

– the State must both assume the fact that women are half the population of Spain, and act accordingly. A democracy that does not act on a fair basis is not a genuine democracy;

– the parity democracy is a necessary mechanism to effectively achieve a real gender equality;

Spain remains, however, a model of women’s effective representation in political bodies.

II. The evolution of women’ s political rights in Romania

The issue of giving women the right to vote was addressed and brought to the attention of the public opinion by women’s associations and leagues of the interwar period.

In 1896, Adela Xenopol pleaded for women’s status and women’s participation in political and state life. Adela founded the Dochia magazine[21]. The Dochia Magazine has become a true battleground for training and promoting women in the most diverse areas of social, political and cultural activity. In 1914, Adela Xenopol, submitted to the Assembly of Deputies a petition for the revision of the Constitution, requesting the right to vote for writers, teachers, and teachers.

Between 1918 and 1923, the activities of the feminist movement in Romania increased, compared to the period before the First World War.

A special exponent of the feminist group was Calypso Botez. Calypso was the founder of the Association for the Civil and Political Emancipation of Romanian Women[22].

By the voice of feminists, in 1922, the issue of women’s right to vote was the subject of debate in Parliament. Romanian feminists had to fight with the prejudices and with the male camp that claimed that the electoral right should be one reserved exclusively for men.

The political rights of women were laid down for the first time in the 1923 Constitution: “Special laws, voted by a two-thirds majority, will determine the conditions under which women may exercise political rights“.

The Electoral Law adopted in 1926 does not clarify the right of women to elect and forbid their right to be elected in Parliament.

For the first time in the history of Romania women were only allowed to vote in 1938, as stipulated in the Constitution. Electoral law gave the right to vote to card-readers from the age of 30, and as most women did not have education, they had a very small number of ladies in the high society. The 1939 election law expressly stipulated that women were not eligible for the Assembly of Deputies[23].

Immediately after the establishment of the Carlist dictatorship, the implementation of the right to vote won by feminists became impossible to put into practice.

Decree no. 2218 of 1946 regarding the exercise of the legislative power stipulated women have the right to vote and can be elected in the Assembly of Deputies under the same conditions as men[24].

Article 18 of the 1948 Constitution: “That all citizens, regardless of gender, nationality, race, religion, degree of culture, profession, including military, magistrates and civil servants, have the right to vote and to be elected in all the bodies of the State. All citizens who have reached the age of 18 and the right to be elected are those who have reached the age of 23“.

Article 21 provided that: Women have equal rights with men in all areas of state, economic, social, cultural, political and private life.“

An extremely important statement is that in equal work the woman has a right to pay equal to the man.

The consolidation of the communist regime in Romania required concerted efforts to promote women and settle in the forefront, according to the Soviet model.

Article 83 of 1952 Constitution - The woman in the People’s Republic of Romania has equal rights with the man in all areas of economic, political, state and cultural life.

The woman has equal rights with the man to work, salary, rest, social insurance and education.“

Also, Article 96 of 1952 Constitution –“ Women have the right to vote and to be elected in the Great National Assembly and in the People’s Advice as well as men.“

Article 17 of 1965 Constitution – “Citizens of the Socialist Republic of Romania, irrespective of nationality, race, sex or religion, are equal in rights in all areas of economic, political, legal, social and cultural life.“

The portrait of the woman in communism is the heroine, bringing together fantastic powers of a devoted mother, a zealous worker and fierce warrior in the name of socialism.

Article 16 of 1991 Constitution: Citizens are equal before the law and the public authorities, without privileges and without discrimination.

No one is above the law.

Public, civil or military functions and dignities may be occupied by persons having only Romanian citizenship and domicile in the country.

Access to public, civil, or military positions or dignities may be granted, according to the law, to persons whose citizenship is Romanian and whose domicile is in Romania.

The Romanian State shall guarantee equal opportunities for men and women to occupy such positions and dignities[25].

After the failed experiences of parliamentary elections of 2008 and 2012, held in compliance with Law no. 35/2008 for the election to the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate and for the amendment and completion of Law No. 67/2004 for the election of local public administration authorities, of Law No. 215/2001 on the local public administration, and of Law No. 393/2004 on the Statute of local electees, which was using the uninominal majority-based vote system, according to the principle of proportional representation, and which led to to an under-representation of women, the Romanian legislator changed the election rules and decided to come back to at-large election system, with closed list.

The Law No. 208/2015 regarding the elections of the Senate and Chamber of Deputies, as well as the organization and functioning of the Permanent Electoral Authority thus stated that senators and deputies shall be elected by election list, according to the principle of proportional representation.

Another important change aimed at the standard for the election of the Chamber of Deputies, that is a deputy to 73,000 inhabitants, while for the Senate election, a senator to 168,000 inhabitants[26].The election law has also appointed the rule according to which the lists of candidates for senators and deputies election shall be drafted in order to provide equal representation of both genders, except the lists with only one candidate[27].

Comparative framework of women percentage in the Romanian Parliament between 1990-2016

|

Legislature |

Total seats |

Number of seats held by women in the Romanian Parliament |

% |

|

1990-1992 |

471 |

30 |

6.36% |

|

1992-1996 |

471 |

19 |

4.03% |

|

1996-2000 |

471 |

23 |

4.88% |

|

2000-2004 |

467 |

56 |

11.99% |

|

2004-2008 |

451 |

53 |

11.75% |

|

2008-2012 |

471 |

46 |

9.76% |

|

2012-2016 |

588 |

68 |

11.56% |

|

2016-2020 |

506 |

88 |

17.39% |

Another basic requirement in the run for office was the list of supporters, which shall include at least 1% of the total number of electors registered to the Electoral register at national level for the lists submitted to Central Electoral Office or at list 1% of the total number of electors registered to the Electoral register, residing within the electoral district where election lists are submitted , with no less than 1.000 electors [28].

For the elections held on 11th of December 2016, there were 6476 candidates, whereof 1797 women, meaning 27,7% of the total number. Among the counties with the highest number of women candidates there were: Giurgiu (39,1%), Bucharest (34,1%), Ilfov (33,3%), Bistrița Năsăud (31,9%), Tulcea and Galați (31,5%). At the other end there were Prahova(19,1%), Hunedoara (20,3%), Cluj (21,8%), Alba (21,9%).

We have selected for the purpose of our research those political parties which won a seat in the Parliament afterwards.

Office nominations coming from political parties for the elections held on 11th of January 2016

|

Political party, political formation, political alliance, independent candidate |

Total candidacies |

Women |

Percentage |

|

PSD |

639 |

182 |

28,5% |

|

PNL |

633 |

160 |

25,3% |

|

UDMR |

638 |

177 |

27,7% |

|

ALDE |

627 |

147 |

23,4% |

|

PMP |

628 |

146 |

23,2% |

|

USR |

482 |

122 |

25,3% |

|

Citizen organizations of minority groups |

50 |

17 |

34% |

|

Independent candidates |

44 |

8 |

18,2% |

Proportion of total number of seats and number of seats held by women[29]

|

Political party, political formation, political alliance, independent candidate |

HOUSE OF DEPUTIES |

SENATE |

% Women / seats |

||||

|

Men |

Women |

Total seats |

Men |

Women |

Total seats |

||

|

PSD |

113 |

41 |

154 |

56 |

11 |

67 |

23,52% |

|

PNL |

58 |

11 |

69 |

25 |

5 |

30 |

16,16% |

|

UDMR |

17 |

4 |

21 |

9 |

0 |

9 |

13,33% |

|

ALDE |

18 |

2 |

20 |

9 |

0 |

9 |

6,89% |

|

PMP |

17 |

1 |

18 |

7 |

1 |

8 |

7,69% |

|

USR |

25 |

5 |

30 |

10 |

3 |

13 |

18,60% |

|

Minorities |

13 |

4 |

17 |

- |

- |

- |

23,52% |

|

TOTAL SEATS |

261 |

68 |

329 |

116 |

20 |

136 |

88 |

|

% femei/ TOTAL SEATS |

HOUSE OF DEPUTIES |

20,66% |

SENATE |

14,70% |

17,39% |

||

Out of a total number of 506 parliamentary seats, only 88 are held by women, meaning 17,39%.

It is interesting to note that even if the political parties and formations submitted a certain number of women on the election lists, the number of seats they actually won is much smaller, revealing the fact most of them ran for unelectable positions.

A brief analysis of the electoral process in 2016, regarding the elections of 11th of December 2016, highlights the following aspects:

– there is no political formation with more than 30% women on their electoral list, despite claiming the opposite before the office nominations;

– political parties did not observe the legal provisions of Art. 52 indent 2 of Law no. 208 of 20th July 2015, which rules: “Lists of candidates for senators and deputies election shall be draw out to provide a balanced representation of both genders, except the lists with one candidate“[30]. To this end, district electoral offices and, therefore, political parties have disobeyed the law by ratifying election lists with only male candidates (for instance, Dambovita county Electoral Office ratified the election list of USR for House of Deputies with only male candidates[31]);

– most of the female candidates on the election lists were appointed for unelectable positions, thus resulting in a very small number of seats won by women for the 2016-2020 legislature, meaning 17,39%, despite leaders of important political groups have emphasized on numerous occasions they will confer women an important role on their candidate lists;

– we notice that Social Democrat Party continues to be the formation with the largest number of women on its electoral lists – 182 female candidates (28,5%), thus attaining the largest number of elected seats held by parliamentary women – 52 female candidates (23,52%), while ALDE included on its election lists only 6,89% de female candidates;

– the elections held on 11th of December 2016, through election by list and based on the principle of proportional representation determined a larger degree of women representation in the Romanian Parliament compared to the previous elections held in Romania;

Even if the percentage of deputy or senator women has increased compared to previous elections, Romania holds a low ranking place in comparison with other European states.

|

STATE |

Unicameral Parliament/Lower House |

Upper House |

||||||

|

Election date |

Seats |

Women |

% F |

Election date |

Seats |

Women |

% F |

|

|

Spain |

28.04.2019 |

350 |

171 |

48.85% |

28.04.2019 |

265 |

103 |

38.68% |

|

Sweden |

9.09.2018 |

349 |

1165 |

47.3% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Finland |

14.04.2019 |

200 |

894 |

47.0% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Norway |

11.09.2017 |

169 |

69 |

40.8% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

France |

11.06.2017 |

577 |

229 |

39.7% |

24.09.2017 |

348 |

112 |

32.2% |

|

Island |

28.10.2017 |

63 |

24 |

38.1% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Belgium |

26.05.2019 |

150 |

57 |

38.0% |

2019 |

60 |

27 |

45.0% |

|

Denmark |

05.06.2019 |

175 |

67 |

37.4% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Austria |

15.10.2017 |

183 |

68 |

37.2% |

N.A. |

61 |

22 |

36.1% |

|

Italy |

4.03.2018 |

630 |

225 |

35.7% |

4.03.2018 |

320 |

110 |

34.4% |

|

Portugal |

06.10.2019 |

230 |

80 |

34.8% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Monaco |

14.02.2018 |

24 |

8 |

33.3% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

United Kingdom |

08.06.2017 |

650 |

208 |

32% |

N.A. |

789 |

209 |

26.4% |

|

Holland |

15.03.2017 |

150 |

50 |

33.33% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Lethonia |

06.10.2018 |

100 |

31 |

31% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Germany |

24.09.2017 |

709 |

219 |

30.9% |

N.A. |

69 |

27 |

39.1% |

|

Poland |

13.10.2019 |

460 |

129 |

28.0% |

13.10.2019 |

100 |

14 |

14.0% |

|

Estonia |

03.03.2019 |

101 |

28 |

27.72% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Bulgaria |

26.03.2017 |

240 |

62 |

25.8% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Luxembourg |

14.10.2018 |

60 |

15 |

25% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Slovenia |

3.06.2018 |

90 |

22 |

24.4% |

20.11.2017 |

40 |

4 |

10% |

|

Moldavia |

24.02.2019 |

101 |

24 |

23.76% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Ireland |

26.02.2016 |

158 |

35 |

22.2% |

25.04.2016 |

60 |

18 |

30.0% |

|

Bosnia-Herzegovina |

7.10.2018 |

42 |

9 |

21.4% |

29.01.2015 |

15 |

2 |

13.3% |

|

Lithuania |

09.10.2016 |

141 |

30 |

21.3% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Czech Republic |

20.10.2017 |

200 |

45 |

22.5% |

05.10.2018 |

81 |

13 |

18.8% |

|

Romania |

11.12.2016 |

329 |

68 |

20.6% |

11.12.2016 |

136 |

20 |

14.7% |

|

Croatia |

11.09.2016 |

151 |

31 |

20.5% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Slovakia |

05.03.2016 |

150 |

30 |

20.0% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Greece |

07.07.2019 |

300 |

56 |

18.66% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Cyprus |

22.05.2016 |

56 |

10 |

17.9% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Hungary |

08.04.2018 |

199 |

25 |

12.6% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Conclusion

Unfortunately, the right representation of women in Parliament, as well as in other local public elected authorities remains a challenge[32].

The factors which determine a low representation are varied:

– a legislation framework that doesn’t firmly regulates a balanced gender representation;

– candidates selection by political parties is not based on professionalism, although party leaders claim this requirement as the main selection criteria in their political rhetoric;

– women are rather focused on a professional career than on a political one;

– a small number of women in leading positions within the elected structures[33];

– misogyny across Romanian society;

– the lack of a culture that promotes equal opportunities and fair treatment in Romania;

– and last but not least, the way politics in Romanian system is done, where a decision is usually made in closed circles (males only), without a previous debate with all members etc.

In order for women to have the best representation within the elected structures, whether is Parliament or local public administration, the election legislation needs to be reformed in due time so the electors and political parties could prepare themselves for the elections to come, by introducing the “zipper“ system, mandating political parties to alternate female and male candidates on candidate lists.

We also consider it is necessary to teach and promote, not only to claim, the principle of equal opportunities and fair treatment. Authorities in charge must put into practice this principle, not just to conduct studies and organize round tables in order to draw the conclusion women are underrepresented.

In December 2017, the Romanian Parliament by amending Law no. 334/2006 regarding the financing of the activity of the political parties and of the electoral campaigns has contributed to the valorisation of the principle of equal opportunities: “For the political parties that promote women on the electoral lists on eligible places, the amount allocated from the state budget will be increased twice in proportion to the number of mandates obtained in the election of women candidates. “

On the other hand, political parties should leave behind political rhetoric and get to implement those actions designed to give women the opportunity to run for office in the same conditions as men, and honest internal competition inside the parties could be a solution.

Bibliography

Paloma Biglino Campos, Partidos Políticos y Mediaciones de la Democracia Directa (Centro de Estudios Politicos y Constitutcionales, 2018).

Francisco Balaguer Callejón (coord.) Manual de derecho constitucional. Volumen II (Madrid: Editorial Tecnos, 2019).

Arend Lijphart, Modele ale democrației. Forme de guvernare și funcționare în treizeci și șase de țări (Iași: Polirom, 2000): 196.

Ștefan Deaconu, Marian Enache, Votul la români. O incursiune în evoluția sistemelor electorale din România (București: C.H. Beck, 2019).

Doina Bordeianu, “Evoluția constituțională a drepturilor electorale ale femeilor în România“, Sfera Politicii, 149 (2010): 54-55.

Claudia Gilia, “Feminizarea politicii românești - un deziderat?“ Sfera Politicii 186 (2015): 3-.17.

Constitution of Spain

Constitution of Romania

Ley Orgánica 5/1985, de 19 de Junio, del régimen electoral general.

Ley Orgánica 6/2002, de 27 de junio, de Partidos Políticos.

Legea nr. 208/2015 privind alegerea Senatului și a Camerei Deputaților, precum și pentru organizarea și funcționarea Autorității Electorale Permanente.

***http://parlamentare2016.bec.ro

NOTE

[1]Maria Soledad Campos Diez, “Principio de Igualdad constitucional“, International Conference: Historia de Europa (1918-2018). Rumania 100 anos, Ciudad Real, 2018.

[2]Clara Campoamor was the one who advocated in the Hemicycle (at the Congress) the introduction of women’s voting right.

[3]By Law 16/24 October 1983, published in the Official Bulletin on 26 October 1983, Instituto de la Mujer was established as an autonomous body within the Ministry of Culture.

[4]This institute was created thanks to the efforts of the women who were the Socialist Party’s representatives in the government.

[5]At present, it is called “The Institute of Women for Equal Opportunities“. For more details:

[6]For details: http://www.juntaelectoralcentral.es/cs/jec/loreg.

[7]The law can be found here: https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2007/BOE-A-2007-6115-consolidado.pdf

[8]Article 44.1 paragraph 3 of LOREG: “No party, federation, coalition or political group may present more than one list of candidates in a constituency - for the election of the Chamber of Deputies or the Senate. A party, that is a member of a federation or a coalition, cannot support its own candidatures in a constituency where there are candidates, for the same election, who belong to the respective federation or coalition.“

[10]Article 162 of LOREG.

[11]With regard to Senators appointed by regional Parliaments, there is one established for each Serl Governing Community and another for every one million inhabitants in their respective territory. The number of Senators that make up this second group is variable. In fact the number has increased in the recent Legislatures as a consequence of the increase in population. Community regulates the election procedure in its Statute, Regional Act and/or Regulation of the House.

[12]Article 44 paragraph 1 of LOREG.

[13]In order to be able to establish themselves, these groups need the support of a percentage of the voters registered in each constituency. These groups are not legally equivalent to political parties, because their activity is not only territorially limited to the respective constituency, but also temporally, to the concrete electoral process, without being able to form permanent political associations (see Sentence 16/83 of the Constitutional Court, the case of Antonio Rovira y otros c. Ayuntamiento de Vilassar).

[14]This condition was introduced by Organic Law 3/2007 on equality between women and men, published in State Gazette no. 71 of 23 March 2007.

[15]This condition was introduced by Organic Law no. 1/2003, published in State Gazette no. 60 of 11 March 2003.

[16]This condition was introduced by Organic Law no. 8/1991 amending LOREG, and it was published in State Gazette no. 63 of 14 March 1991.

[17]Article 169 paragraph 4 of LOREG.

[18]Arend Lijphart, Modele ale democrației. Forme de guvernare și funcționare în treizeci și șase de țări (Iași: Polirom, 2000): 196.

[19]See: http://www.senado.es/web/conocersenado/temasclave/presenciamujeres/listasenadoras/index.html

[20]Ana Marrades Puig, “Los derechos políticos de las mujeres: evolución y retos“, Cuadernos constitucionales de la Cátedra Fadrique Furió Ceriol, ISSN 1133-7087, Nº 36-37, 2001, pages 211 & 212 (The text can be found here: http://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/3103308.pdf).

[21]Camelia Popescu,“Lupta pentru dreptul de vot în perioada interbelică“

[22]Doina Bordeianu, “Evoluția constituțională a drepturilor electorale ale femeilor în România“, Sfera Politicii, 149 (2010): 54-55.

[23]Chapter 1, article 4 paragraph 2 of the Electoral Law for the Assembly of Deputies and the Senate of May 9, 1939. For details, Ștefan Deaconu, Marian Enache, Votul la români. O incursiune în evoluția sistemelor electorale din România (București: C.H. Beck, 2019).

[24]Article 2 of the Decree no 2218/1946, M. Of no.161 from the 15 July 1946.

[25]The Constitution of Romania of 1991 was amended and completed by the Law No. 429/2003 on the revision of the Constitution of Romania.

[26]Article 5 indent 1-3 of Law No. 208/2015 regarding the elections of the Senate and Chamber of Deputies, as well as the organization and functioning of the Permanent Electoral Authority.

[27]Article 52 indent 2 of Law no. 208/2015.

[28]Article 54 indent 1 and 2 of Law no. 208/2015.

[29]For details: http://parlamentare2016.bec.ro/statistici/

[30]See http://ongen.ro/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/RAPORT-Femeile-candidate-%C3%AEn-alegerile-parlamentare-din-11-decembrie-2016.pdf

[32]Claudia Gilia, “Feminizarea politicii românești - un deziderat?“ Sfera Politicii 186 (2015): 3-.17.

[33]During the 2016-2020 legislature, in the parliamentary session September-December 2019, within the House of Deputies leading board, out of 12 members of the Permanent Office, there is only 2 women as we speak (October 2019): a vice-president and a secretary. While the Senate Permanent Office has 2 women: a vice-president and a secretary. Out of 21 Permanent Commissions operating in the House of Deputies, only 2 of them are led by women (the Commission of Foreign Policy and the Commission of Equal Opportunities for Women and Men). At the Senate, out of 22 Permanent Commissions, only 2 of them are led by women (the Commission for Agriculture, Forestry and Rural Development and the Commission for European Affairs).